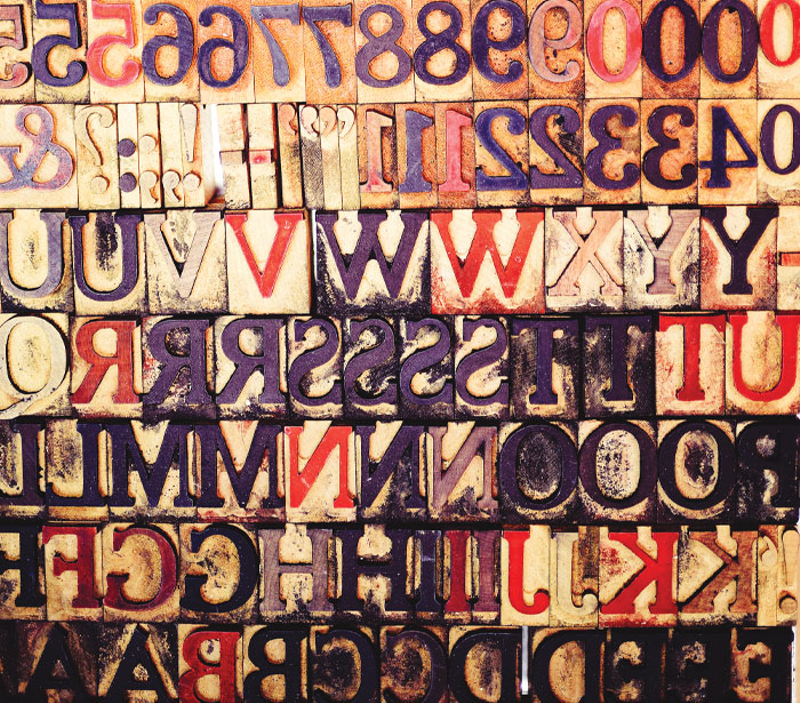

The world changed forever when Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the mid-15th century. Moveable type ushered in a new marketplace of ideas, fostering literacy, spreading news and democratizing the way people obtained information.

If asked what the most revolutionary innovation of the second millennium was, you’d be hard-pressed — no pun intended — to find an answer different from letterpress printing. But the advent of offset printing in the mid-20th century marked a decline in letterpress’ popularity and functionality. Without its cutting edge, letterpress printing became obsolete, a thing of the past.

Until recently. A new documentary from Erin Beckloff and Andrew Quinn, Pressing On, traces the resurgence of letterpress and the people who are keeping it alive.

“It was the internet of its day,” says Beckloff, an assistant professor in graphic design at Miami University. “Letterpress disseminated knowledge all around the world when it was first created, but the film is also about the relationships in this community of individuals and how there’s an interesting transformation happening with how their knowledge is being passed down to the next generation.”

The irony doesn’t escape Beckloff that the project, which centers on a technology perfected about 550 years ago, was funded through the internet of our day; a Kickstarter campaign raised more than $71,000, turning her dream into a reality in less than a month. Without the generosity of the letterpress community, the film likely wouldn’t have been made.

“It was an example of a community coming together,” Beckloff says. “People donated posters and type. People gave workshops and apprenticeships in their shops as rewards because they wanted this to happen. It was amazing to see.”

Beckloff’s interest in letterpress can be traced back to a Kelsey tabletop press given to her by her in-laws as an engagement gift seven years ago. When she couldn’t find a traditional print apprenticeship, Beckloff instead interned for the esteemed Hatch Show Print letterpress print shop in Nashville, Tenn. (in operation since 1879), where she learned the basics of letterpress printing and developed a passion for the industry.

“One letterpress tends to lead to another,” she says. “I now have six presses and my own home shop.”

The idea to make a feature documentary about letterpress culture hatched when Beckloff was interviewing an 83-year-old printing mentor about his technique. What started out as a recording for posterity changed when she realized that countless other people with letterpress memories and methods were also out there; Beckloff decided a film would preserve these the best. Needing a little help, Beckloff struck a deal with Bayonet Media in Indianapolis and found a co-director in Quinn, who was itching to make his first feature.

Pressing On will be released early next year and will grant viewers an immersive account of not only letterpress’ distinguished practitioners, but also a culture that increasingly embraces the merging of historic tradition with new media.

Today, the oldest printing technique provides a remedy to an aggressively less tactile world. When working on a laptop, graphic designers or hobbyists interested in design aren’t engaging many senses. But letterpress printing offers an incredibly stimulating experience. From the cadence of the turning wheels and cylinders to the dizzying odor of ink, the physicality of operating the machine is a process steeped in tradition. The culture of letterpress printers old and new possesses a stubbornness, a refusal to let what they love become obsolescent.

Unlike modern printing methods — which use digital files and computerized machines — letterpress is a form of relief printing that originally used elevated type or engraved images to stamp inked replicas of a design onto a surface. Basically, printers lined up blocks of desired letters or images in the correct order, applied ink and then used a human-operated machine to press the inky letters onto paper to create a word or image; letterpress printing is literally pressing letters into a surface.

Although the first letterpress relied on moveable blocks of type, the 20th century introduced photopolymer plates (light-sensitive printing plates) that can integrate digital designs. Today, younger carriers of the letterpress torch are using their MacBooks to forgo hand-set designs, making seamless photosensitive plates that can both faintly imprint — “kiss” — the surface of what is being printed on or leave a deeper impression called a “bite.” In an ironic twist, it’s digital natives that are breathing new life into a machine seen by the uninitiated as just a piece of archaic gadgetry.

The general consensus isn’t that these computerized appendages to letterpress corrupt the art — far from it. “The people in the film just want the equipment to be used, whichever way possible,” Beckloff says.

Of course, Beckloff harbors no doubts about the web’s power to connect us. After all, it was the force of social media that ushered the film into reality. “Technology is what keeps us connected,” she says, implying both old and new methods.

For many younger protégés, the letterpress renaissance bloomed in the aughts, when artists sought to reinstate some form of intimate craftsmanship in their work. That this particular craft requires a large investment of time and energy only made it more appealing. Unlike creating something using InDesign, the reward with letterpress — a piece of design with shallow grooves that you can touch with the grimy hands that legitimize your labor — actually leaves an impression. Literally.

“(With digital design) you spend so much time behind a screen, putting hours of work in, but then you just have a flash drive or a link to something. It’s frustrating that you put in all this time and effort and all you have to show for it are technically some ones and zeroes,” Quinn says. “With letterpress, you can look at your hands and see the ink. In the end of you have a physical thing that you can hold onto and give to someone.”

While longtime printers tend to be older, blue-collar males, Quinn and Beckloff say the new wave is comprised overwhelmingly of creative class females. The film explores the unlikely friendships between two generations that blur letterpress’ role as trade and art. As younger graphic designers learn from 80-year-olds who are using heirloom contraptions handed down through the family, they learn the same ceremonial acts of letterpress printing.

It’s an inheritance that is just as much emotional as it is technical. In the film’s sleekly produced trailer, the printers convey almost spiritual experiences with letterpress. No wonder — engaging your body to produce a piece of art or writing on a letterpress is a choreography of labor that immediately binds you to a long history of other printers that published a range of groundbreaking texts, from Gutenberg’s bible to Shakespeare’s folios to some of the most important news of the past few hundred years (in the early 1900s, this paper would’ve been printed on letterpress).

The appeal to the mechanics is much more than a nostalgic throwback — it’s a way to connect with people who made history.

Although printing was primarily a working class arena, that could be changing today. Unless you’re using your machine to print dollars, buying a letterpress is a steep investment that might take years to profit from. Acquiring a good-sized letterpress could set you back a couple thousand dollars, not to mention the cost of maintenance, extra widgets and sundry other materials. But for many, this is part of letterpress’ unique pleasure, and most typomaniacs aren’t in it for the money.

“I warn people, it’s like a disease,” says an older man in the trailer, letting out a chuckle. He looks perfectly healthy.

For the film, Beckloff and Quinn drove two carloads of equipment across the Rust Belt last summer, finding pockets of letterpress communities in places like Hamilton County, Chicago, Nashville, Tenn. and Indianapolis. During the interview process, one person’s story would lead them to another, and with this they found a narrative of letterpress preservers in the Midwest. Local presses include the boutique Pistachio Press in Clifton, Steam Whistle Letterpress in Newport and Igloo Letterpress in Worthington.

“The Midwest was a hotbed for printing in the country, historically,” Quinn says. “In 1920, there was almost a printshop on almost every corner.”

That’s obviously not the case now, but enthusiasts like Beckloff are helping designers rediscover the joys of mechanical printing. While teaching as an adjunct at Miami, Beckloff salvaged the university’s letterpress shop — which was about to be scrapped after 25 years of going unused — and established a letterpress course (titled “Hand Media, Letterpress & Book Arts”) within the university’s College of Creative Arts.

Organizations like the Amalgamated Printers’ Association, of which Beckloff is a member, are also helping to conserve the precious art of letterpress.

“There’s a symbiosis between the machinery and the people,” Quinn says. “It’s given people purpose, keeping this historic means of communication alive. They become the gatekeepers and guardians of the craft.”

Quinn adds that many old-time printers started out hoarding materials — fonts, blocks, rollers — without knowing why, until they were surrounded by a library of letterpress parts. By turning a hobby into a lifestyle, they’ve created their own world.

In the 21st century, letterpress finds a consumership in those looking to make paper more personal. Wedding invitations, posters, stationery, holiday and business cards are marketed to younger prosumers looking to add a dimension of texture (and supposedly authenticity) to their missives. This, perhaps, has to do with branding (in both senses of the word). Because letterpress is so tangled in the heritage brands and vintage-industrial aesthetic that has captivated the consumer imagination, old-school printing provides an avenue for artists to better brand — figuratively and actually — their steampunk ethos.

Quinn likens the resurgence of letterpress to that of vinyl, but it’s easy to conjure an entire imaginary shelf of low-tech items making comebacks in the clumsily named Information Age: Polaroid and film cameras, typewriters and even flip-phones are experiencing a second wind as people try to escape the distraction and unnecessary complexity of so-called “smart” technology. Letterpress printing naturally embodies the principles of “slow living” that so many disenfranchised Americans are flocking to, a movement that insists on experiencing life in the moment, without the chaotic immediacy of the web.

“As designers get older and find certain roots, they long for the ritual of physical media,” says Quinn, who knew little about letterpress before the film but is now fascinated. “When they find those mechanical parallels, that can inform their digital graphic design. It was the first version of that.”

Pressing On is now in post-production and is already lined up to play at film festivals across the country. Beckloff is hopeful that viewers will gain her fascination with letterpress printing, and she should be. It’s a big responsibility to make her Kickstarter audience who funded the film satisfied. Beckloff doesn’t seem to worry too much about that, though. After all, a letterpress printer’s least favorite thing is often also their most favorite thing — a blank slate.

Find more information about PRESSING ON and future screening dates at letterpressfilm.com.