Cincinnati is emerging as a vital presence on the current cinematic landscape. After nearly two decades of spotty activity, the Queen City has become a significant movie production destination in recent years.

There are a number of reasons for this development, the most obvious being Cincinnati’s architecture, the area’s diverse terrain and the relatively inexpensive nature of production costs. Then there are the dedicated efforts of various behind-the-scenes local entities to entice a series of notable productions, including George Clooney’s The Ides of March, Todd Haynes’ Carol, Anna Rose Holmer’s The Fits and Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer.

Yet one movie featuring Cincinnati-shot scenes that reigns supreme with cinephiles came well before all this recent activity — John Huston’s 1950 masterpiece, The Asphalt Jungle. A recent Criterion Collection Blu-ray release, armed with a trove of extras, reveals the landmark black-and-white noir to be as visceral and groundbreaking as the day it surfaced nearly 70 years ago.

Adapted for the screen by Huston and Ben Maddow from W.R. Burnett’s hard-boiled crime novel, The Asphalt Jungle centers on a group of men desperate to get what they don’t have or what they think they need — men often dreaming of a future marked by nostalgia for the past. It’s a post-classical Hollywood anomaly told from the point of view of the criminals — an existential heist movie that shows as much empathy for the “bad guys” as it does for the “good guys.”

The Asphalt Jungle opens with a low-angle shot of the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge from the east side of what is now the public landing. The camera pans slowly right to reveal Cincinnati’s two most enduring buildings — the Carew Tower and what was then the Central Trust Building (now PNC Tower) — looming hazily in the background. The musical score, laced with punchy horns and ominous strings, sets the mood as a police car drives past long-gone warehouses on the Ohio River waterfront. Then the film cuts to a shot of the police car driving north on what seems to be Vine Street, with nondescript, mostly dingy buildings lining its ascent toward Clifton.

And then one of the most indelible shots in The Asphalt Jungle — Sterling Hayden, playing the hoodlum Dix Handley, hides behind a pillar as the police car drives past. Moments later Dix enters a small, meager-looking Over-the-Rhine café marked by the words “American Food’ and “Home Cooking.” Who is this lanky man in a suit and hat? Why is he hiding? And why is he walking around what seem to be deserted, rundown sections of Cincinnati?

The entire opening sequence takes less than three minutes to unfold — and features the only undeniably recognizable shots of Cincinnati — but it sets a pungent and highly effective tone for the story to follow. We’re in a grimy post-war unnamed Midwestern American city where crime is an everyday occurrence and everyone is trying to get “out from under.”

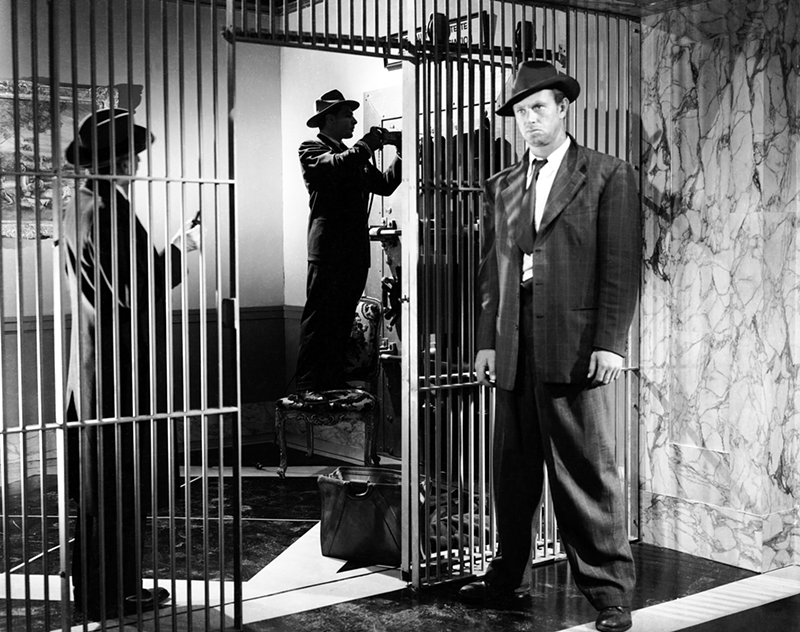

Joining Dix in this goal is Doc (Sam Jaffe), a professional criminal who, as the movie opens, has just finished an extended prison sentence. Doc has an idea for one last score, a jewel heist that will allow him to retire to Mexico. But he needs help, which is when he meets up with Cobby (Marc Lawrence), a bookie who suggests he meets Alonzo Emmerich (Louis Calhern), a lawyer and seemingly upstanding citizen who agrees to bankroll the heist.

These men, all yearning to transcend their circumstances, dominate The Asphalt Jungle — none more curious or compelling than Dix, played with nuanced menace by a never-better Hayden.

But The Asphalt Jungle is not exclusively the domain of men; it also possesses the screen debut of Marilyn Monroe, who plays Alonzo’s mistress, Angela. Huston introduces Monroe, who lies lazily on a couch, with a carefully staged shot in which Alonzo gazes down at her from above. Angela’s demeanor and visage are pure Monroe — innocence mixed with seduction.

Monroe only has a few scenes, little more than five minutes total, but her presence, much like the brief establishing shots of various Cincinnati cityscapes, leaves a distinctive impression in a movie full of them. ©