Under Hamilton County Prosecutor Joe Deters, a criminal forfeiture fund statutorily intended for law enforcement expenses and drug abuse prevention has been tapped regularly for mundane purchases and, on two occasions, sketchy consulting contracts that Deters won’t discuss.

• Since the beginning of 2015, the prosecutor’s office has spent about $200,000 on real estate consulting by a local man with a history of financial problems — and has no records of his consulting contributions.

• In 2015, the office spent almost $15,000 on “briefcases for attorneys” and nearly the same amount on furniture for a grand jury office.

• Since 2014, the office has spent $3,800 toward the personal dues of Deters in three bar associations and a local police group.

• And as CityBeat reported in June, the office spent $2.2 million over 12 years on information technology contracts with a former employee — a friend of Deters — without seeking competitive bids.

What these expenditures have in common is that the money comes from a special account funded by property and cash seized from criminal offenders. The accounts, called Law Enforcement Trust Funds in Ohio, were created by federal and state laws meant to divert money from the bad guys to the good guys.

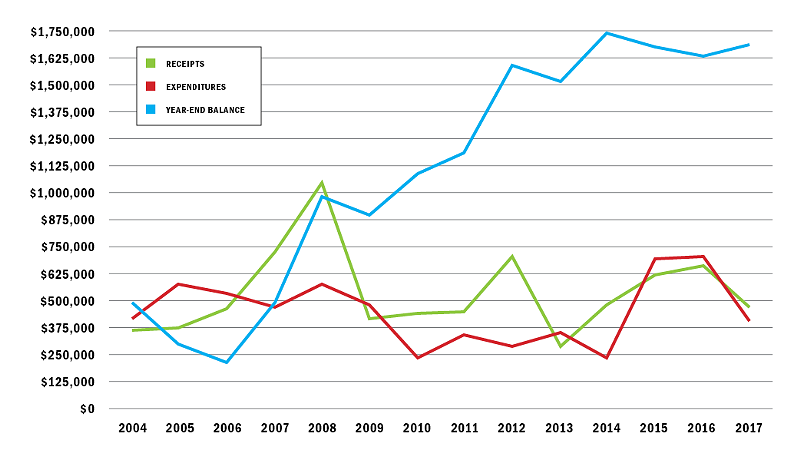

But Ohio’s law leaves a lot to the discretion of prosecutors, sheriffs and cities that maintain such funds. What’s more, the Hamilton County prosecutor’s office has built up a $1.7 million pot that isn’t posted online or included in county budget documents. It isn’t audited and it is used for purchases that don’t seem to fit the intent of the law.

“This is not something peculiar to Ohio,” says Dick Carpenter II, director of strategic research for the Institute of Justice, a citizens’ rights group in Arlington, Va. “This is a problem all over the country.”

Loose guidelines

How Deters, Sheriff Jim Neil and other law enforcement agencies in Ohio spend their LETF money is dictated by state law. It can be used to defray the cost complex investigations or prosecutions, training and shutting down meth labs. Ten to 20 percent of it must go toward “community preventive education programs” chosen by the forfeiture fund operator. And money can be spent on “other law enforcement purposes” that the operator “determines to be appropriate.”

That’s where the law ends and subjectivity begins. Neil’s spending ledgers appear very sheriff-like, laden with outlays on vehicles, helicopter repairs, ammunition, phone bills, drug buys, uniforms and hardware store purchases. Deters’ LETF spends heavily on outside law firms, computer services, trial-related expenses, travel, training and depositions.

But Deters’ office also uses forfeiture money for a $1,850-a-month parking tab, furniture, tables at awards banquets, a media room TV, a microwave oven, the briefcases and $855 worth of stuffed animals for children of grand jurors. In 2008, his office gave $3,200 to the St. Xavier High School lacrosse program.

Responding to CityBeat’s questions by email, Deters spokeswoman Julie Wilson was terse in defending the purchases.

“Any expenditure from the LETF fund has been deemed appropriate by Mr. Deters,” she wrote.

Carpenter, whose book Policing for Profit scrutinized civil forfeiture laws, said prosecutors and law enforcement officials should not be allowed to dictate unilaterally the spending of forfeited money.

“There’s less likelihood of questions coming up if it’s done through a traditional appropriations process that is exposed to the light of day,” he says, “because then it’s going to go through various levels of review by committees and subcommittees. There’ll be public hearings. There’ll be multiple people who are involved in the decision-making.

“(Deters) appears to be in complete compliance with the law. The problem is more the law than it is how this person is behaving,” Carpenter says. “There’s nothing probably illegal going on here, but there’s a greater potential for something like that to happen when decisions are made outside the normal appropriations process.”

As in Illinois. There a former prosecutor was indicted earlier this month for allegedly using forfeiture funds to buy a car and pay for personal business expenses.

Ohio was one of many states engaging in the controversial practice of seizing — and cashing in — assets taken from people merely accused of crimes. Until January, that is, when a bill co-sponsored by Rep. Tom Brinkman, R-Mount Lookout, became law. It requires a conviction ahead of forfeiture.

The law did not address how forfeited money is spent, however. Which means Deters is free to continue making moribund purchases and awarding head-scratching consulting contracts from the fund.

A penchant for consultants

In June, CityBeat reported that Deters, since taking office in 2005, had given $2.2 million worth of computer systems and software work to an old friend, Dennis Lima, without obtaining competitive bids. The contracts were given to Lima’s companies as “consultants,” the hiring of whom is exempt from Ohio’s competitive bidding law. Other Hamilton County offices, such as the sheriff, auditor and board of commissioners, award computer systems contracts to the lowest bidder to save money.

Another Deters acquaintance, Jim Youngblood, is on the forfeiture fund payroll. In January 2015, the prosecutor’s office hired him to provide “professional real estate consulting services” — for $6,666 a month, or $80,000 a year, an amount Youngblood continues to receive.

The two-paragraph contract says the work will include “evaluation of the selection, acquisition and cost of real estate in conjunction with projects which the prosecuting attorney provides legal services to various county officials.” Yet when CityBeat sent Deters’ office a public records request for anything Youngblood has produced, Wilson replied that there are no such records.

CityBeat asked Wilson to verbally cite any examples of Youngblood’s work, how he might have saved the county money in real estate deals and the frequency of his consultations. Her response? “We have no further comment on Mr. Youngblood.” Youngblood did not return phone calls.

Public records cast Youngblood, who is 74 years old and whose full name is Raymond J. Youngblood, in an unsettling light.

As a former real estate broker, he was fined $500 by the Ohio Real Estate Commission in 1997 for failing to maintain a trust account. He hasn’t had an Ohio real estate license for more than 15 years now. He filed personal bankruptcy in 1998. And in 2000, more than a decade of pursuit by the IRS for not paying federal income taxes culminated in his guilty plea to filing a false tax return. A judge put him on probation for three years and ordered him to pay $32,661.

Youngblood's Facebook page shows linkages to Deters. He lists as friends a brother, a nephew and a sister-in-law of Deters. He also lists several local Republican officials and a woman photographed with Deters.

If Youngblood has advised on county real estate matters for almost three years, it isn’t widely known to other county officials.

Ralph Linne, director of Hamilton County facilities, including the courthouse, county administration building and prosecutor’s building, did not recognize Youngblood’s name and said he has no dealings with him. Jim Knapp, chief of compliance for the Sheriff’s Office, said likewise. Youngblood did help the Coroner's Office in its search for a bigger facility, to no avail.

"Mr. Youngblood found a few locations that were considered, vetted and eventually disqualified," said Chief Administrator Andrea Hatten.

When forfeiture funds top $100,000, state law dictates that 20 percent of the money go toward “community preventive education programs.” Deters’ office does spread the ill-gotten wealth. It gave $25,000 to New Prospect Baptist Church last year and $10,000 apiece this year to the Marvin Lewis Community Fund, the Reds Community Fund, the Mack Family Foundation, the Boy Scouts of America and Women of Alabaster Ministries. It has given $166,000 to DePaul Cristo Rey High School since it opened in 2011.

DePaul Cristo Rey is a private, college-preparatory school in Clifton for students from low-income families. It uses the money for drug prevention education and a work-study program that places students with 130 employers.

“The value of the Corporate Work Study Program and the support of its partners, including the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, cannot be understated,” says the school’s president, Sister Jeanne Bessette. “These partners are making an investment in the lives of our community’s young people and helping them to avoid the dangers and self-destructive behaviors associated with drug use.”

In the first seven years upon returning to office in 2005, Deters sprinkled about $100,000 in forfeited funds across 14 K-12 schools. All but one were Catholic schools. Taylor High School was the only public school to receive money.

CONTACT JAMES McNAIR: [email protected], 513-914-2736 or @jmacnews on Twitter