One day about six decades ago, a tremendous roar rippled through Melvin Grier's classroom at Holy Trinity School on West Fifth and Mound streets in Cincinnati's West End. He and his classmates ran to a window to see Holy Trinity’s neighboring 99-year-old church building being torn to the ground.

That was just the beginning.

By 1958, the school itself was sold and demolished to make way for I-75, according to Cincinnati Archdiocese records. It was the end of Holy Trinity in the West End, and the acceleration of a process city and federal officials were calling urban renewal.

“We were still living there when they were tearing buildings down,” Grier says of watching the process unfold. “Imagine if the house you grew up in wasn’t there. And the next house you lived in wasn’t there. Everything from my childhood is gone.”

A retaining wall still stands near to the space once occupied by the four-story cold water flat at 651 W. Fifth St. Grier grew up in with his widower father. It’s the last remnant of the neighborhood he recognizes, he says.

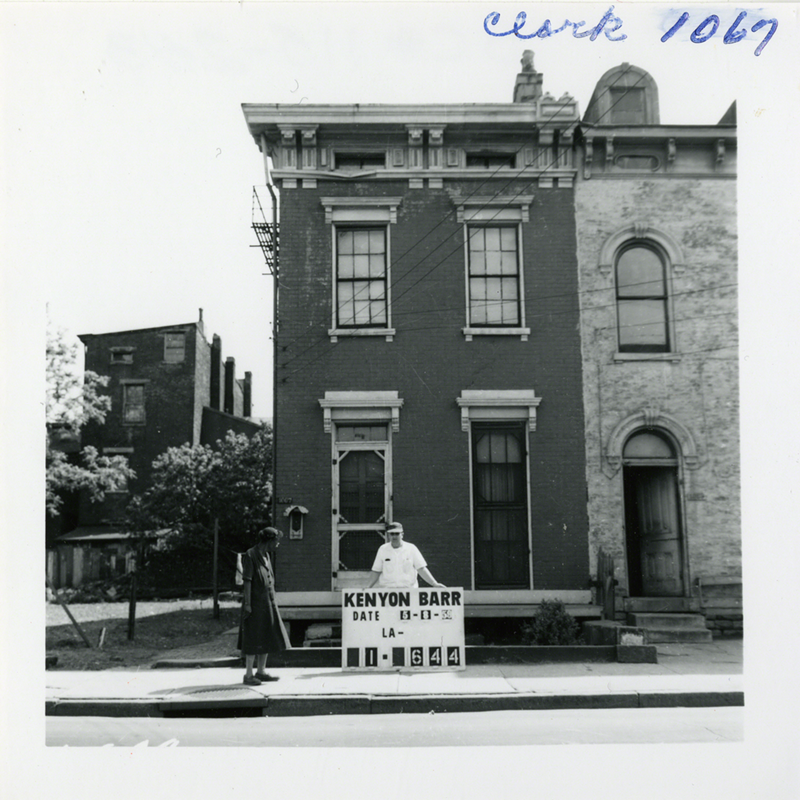

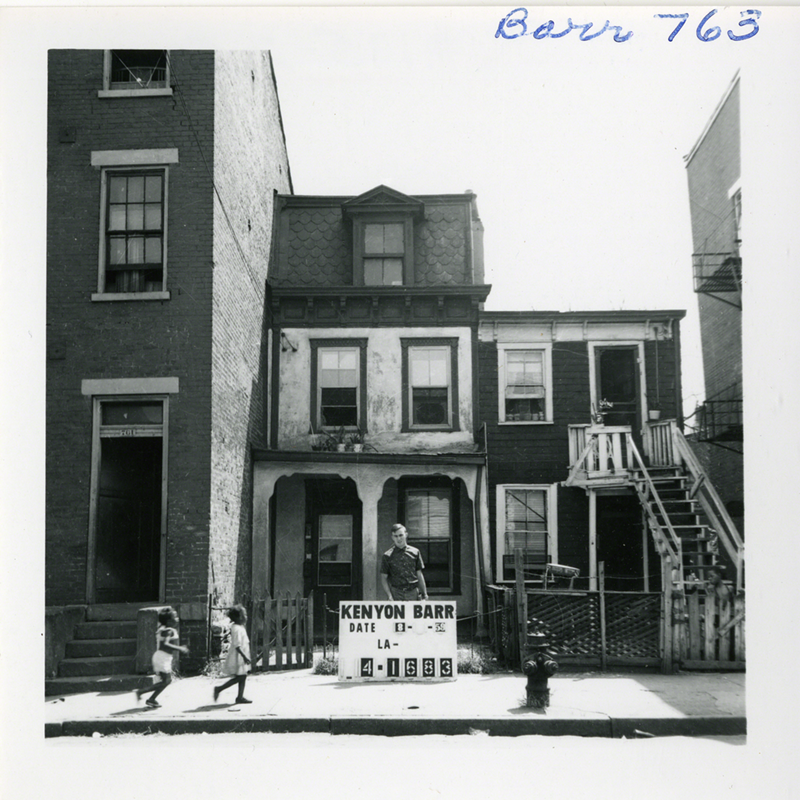

That and 2,800 photographs. A new exhibit and panel series by historic preservationist and University of Cincinnati doctoral student Anne Steinert called Finding Kenyon-Barr is raising the ghosts of a demolished West End with archival photos the city snapped of many doomed buildings before it tore them down.

Today, the Cincinnati Museum Center holds those photos. Steinert and volunteers spent time narrowing down the museum’s cache to 39, which are displayed extra-large on the walls of a gallery provided by The Community Builders at 1202 Linn St. in the West End. Portions of 1934 Sanborn Insurance maps are posted next to these photographs to give a sense of the density of the neighborhood, and tablet computers in the gallery let attendees see the spots as they exist today.

The pictures — some capturing tense or playful interactions between city employees and neighborhood residents — provide haunting memorials to the lost neighborhood, and, some say, a reminder about contemporary urban change.

"The photographic record not only captures some 2,800 structures built in the late 19th Century but also the local business community and residents going about their daily lives chatting with neighbors, shopping at the local meat market and kids playing in the street," Museum Center Photography curator Jim DaMico says. "For me, the most fascinating aspects of the collection are the residents we see in some of the photographs. Who are these people and what are they thinking when they have the man from the city standing in front of their home with this oversized sign?"

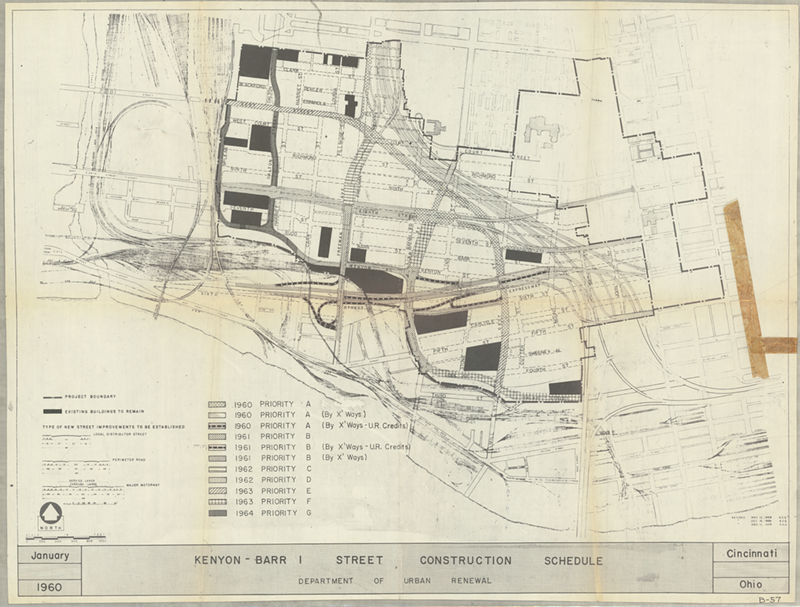

The same year Holy Trinity’s last building was shuttered and razed, the city of Cincinnati approved final plans for a feat astonishing in its size and for its relative obscurity today: the removal of an entire neighborhood.

By the time it was all over in the 1960s, the city had torn down thousands of buildings containing 10,000 units of housing, hundreds of businesses and nearly every place of worship in the neighborhood, city documents show. An area the size of Over-the-Rhine occupying the flat, sprawling plain west of downtown was simply wiped clean in the name of highway construction, what planning documents call “slum clearance” and a landing spot for light industry.

City documents at the time estimate the population of this neighborhood, which demolition planners dubbed Kenyon-Barr, to be more than 25,000 people. Most of them were black. Today, just 120 people live in the grey, mostly empty Census tract designated as Queensgate that roughly corresponds to the area demolished. A few small buildings and a single intact block of Carr Street are largely all that remains of the once-bustling neighborhood.

“There is so little left,” Steinert says of the neighborhood. “We have nothing to show for this place that was 297 acres of dense urban land.”

The name itself is an artifact of disappointment. After the city had little success selling the newly cleared land to the more than 100 businesses it called, a marketing firm suggested changing the name to Queensgate to make it more appealing.

“It’s a rebranding of a neighborhood that was a vital, busy, interesting, beautiful place where real people lived,” Steinert says.

Though many of its buildings weren't up to code, it wasn’t just a slum to be cleared, residents like Grier and author John Harshaw say. It was the cultural epicenter of Cincinnati’s black community and also a place to learn about others.

Harshaw lived at 1030 Seventh St., “a moon walk from Price Hill,” he says.

“It was a grand mixture of people,” Harshaw says. “Irish, Jewish, black, people from everywhere. Everyone looked after everyone else.”

Harshaw remembers the food — learning about sauerkraut, kielbasa and other items from European immigrant families, as well as the hot dogs at black theaters like the Regency and the Lincoln where music legends like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington played.

His most prominent memory, however, is a lesson about race and power he learned in the West End that set him on the course to becoming a bank president.

After working a day at Shillito’s Department Store downtown while he was in high school, Harshaw went to the neighborhood’s sole bank to open a savings account with his paycheck. The teller told him the bank’s policy prohibited giving accounts to blacks.

He went to his neighbor Abe Faust, a Russian immigrant, to cash the check at his grocery store. He related to Faust what the bank told him. Harshaw says Faust marched him back to the bank, where the grocer confronted the bank teller and told him he and his business associates would withdraw their business if Harshaw wasn’t given a savings account. The bank relented.

“I said, ‘I need to make sure this doesn’t happen any more,’ ” Harshaw says. “That’s when I started wanting to be a banker.”

Harshaw, Grier and other former residents say stories like these are what really define the lost part of the West End. After the demolitions, Harshaw’s family moved to Laurel Homes, a federal housing project just north of the neighborhood that had recently been de-segregated. Grier, who would go on to spend three decades with the Cincinnati Post as an acclaimed photojournalist, moved to Avondale following the demolitions. It was a mixed experience, he says.

The houses were nicer in Avondale, with hot water, big lawns and more space. But the social and cultural fabric Grier knew was torn apart by the destruction of the West End. He mourned the loss of proximity to jazz venues like the Cotton Club — just a block from his home — where he would sit outside and listen as musicians in their fine suits filed in and out.

“What was taking place, in addition to destruction of homes, was the destruction of a cultural entity,” he says. “We had the storefront churches. We had Catholic churches. We had jazz clubs. We had bars. We had restaurants. All of this was run by African Americans. And it all absolutely went away. I think we’ve paid a big price for that.”

The disruption of the community and resettlement of its predominantly black members set demographic and economic patterns that continue today. As black residents forced out of the West End streamed into neighborhoods like Avondale, Mount Auburn, Walnut Hills and elsewhere, they experienced an array of new systemic challenges officials seem not to have anticipated or cared to deal with.

A 1958 letter from then-NAACP Cincinnati Executive Secretary Kenneth Banks to the organization’s national housing office calls Cincinnati’s approach to resettlement “casual” and explains that the city had yet to identify enough places for blacks to move into. He wrote that developers and banks showed little interest in building homes for blacks or lending money to them, and that the city’s lack of statistics about the West End showed an apparent disinterest in even knowing exactly how many families the highway would displace.

The confluence of policy decisions and market dynamics following urban renewal put up huge obstacles for blacks. In 2015, CityBeat detailed the journey of one former West End resident, Gus Whitfield, whose story illustrates those challenges.

For Harshaw, the more immediate disconnects in personal relationships were the biggest loss in the aftermath of the West End’s erasure.

“No longer could Abe Faust and his wife Mary look out the window and say, ‘Hey, John, get off that car,’ ” Harshaw says of life after the demoltions. “That didn’t happen anymore because we were all spread out.”

Steinert says the photos — now on display for the public to see, thanks to Finding Kenyon-Barr — are a reminder of that vibrancy of the West End. In a new era of rapid urban change in Over-the-Rhine, Walnut Hills and other neighborhoods — Grier brings up institutional expansion in Avondale — there’s social and political import in the exhibition. But the photos are also deeply personal. Harshaw says he cried when he first found the photo of his house in the Museum Center’s collection.

“I blew it up and hung it on the wall,” he says. “There were my grandparents and all my friends.”

• Finding Kenyon Barr is open Sundays Noon-4 p.m., Tuesdays 3-7 p.m. and Fridays 10 a.m. - 2 p.m. Panel discussions will take place Nov. 16 and 30 and Dec. 14. All begin at 6:30 p.m. at 1202 Linn street.