The world looked bright to progressives in November of 2014. Obama was rolling in year six of his eight, shaping policies at all levels for a more just and caring nation, and there was particularly good momentum in gay rights.

Centuries-old bigotry seemed amazingly on the run as same-sex marriage initiatives sprouted and found some success in states across America. Even Alabama was soon to wobble, with its own Prague Spring of court-ordered gay nuptials in early 2015.

Hot damn, LGBTQ people and their loved ones and friends, partying in the park in Birmingham and Montgomery! Twenty years earlier, you’d have given Martians a better chance of pulling that off.

Ohio wasn’t budging, to its stolid discredit, but heck, we were only eight months away from seeing the Supreme Court handle the issue for Buckeyes and everyone else by legalizing same-sex marriage across the country. And so it was that on Nov. 19, 2014, when openly gay basketball player Jason Collins announced his retirement after 13 NBA seasons, he could do it with a message that warmed and cheered us.

Collins had become a progressive hero in early 2014, playing the final 22 games of his career 735 after coming out. He was an eight-minute-per-game reserve on the back nine of his tenure, but he became the first “out” player in any of the four major U.S. team sports.

And short as his exposure was, it had all just gone so well. Fans had cheered, league executives and coaches offered praise and teammates had accepted him without a ripple, exposing the canard that an openly gay player would cause unacceptable unease in a men’s pro locker room. His Brooklyn Nets went 10-2 in the first 12 games after he signed as a free agent.

Thus, when Collins proclaimed in his retirement announcement, “It shows how far we’ve come,” we nodded like bobbleheads and believed, expecting much more very soon.

But now, three years later, the progressive cause finds itself set back on many fronts, and the emergence of gay players is at a dead stop in the four major sports.

Collins, in fact, remains the only player to do what he did in the NBA, NFL, NHL or major league baseball. He came out with the words, “If I had my way, someone else would have already done this.”

But his own action has not cracked wide the path for others. The NFL St. Louis Rams did draft an openly gay player in spring of 2014, defensive end Michael Sam, and Sam played in the ’14 preseason with no noticeable disruption to his team. But he was released in final cuts and never played in a regular-season game.

I reached Collins by phone this week and asked him for his reaction to his still-singular status. He paused a moment before speaking.

“My reaction to that is that I’m upset. No, a better word is just ‘disappointed’ that no other players in the four leagues have stepped forward. But I am even more determined to help create an environment where those athletes do feel comfortable stepping forward.”

But what about “those athletes?” One can speculate that there must be well more than 100, based roughly on the four leagues’ total roster spots and a Gallup estimate that 3.8 percent of people identify as gay. Does Collins for a fact know of some?

“The simple answer,” he said, pausing, “is yes. They might not have told me, but they’ve told someone that I know and trust. The answer to your question is yes.”

Collins remains employed by the NBA as an “NBA Cares Ambassador.” It’s a community relations type of post, and one of his duties is giving a presentation each year to NBA rookies.

“We talk to them about things like language in the locker room,” he said. “We try to increase their awareness with respect to LGBT issues.”

It’s an example of how the four leagues, and most of their franchises, are supportive of mild efforts to “change the culture.” The NFL reacted to the Michael Sam situation by proclaiming itself a “football meritocracy,” where sexual identity would not hinder one’s chances for success.

The Bengals, during my tenure as public relations director, developed a similar statement. The Reds’ recent promotional schedules have included a “Pride Night,” and hockey has declared in conjunction with its players’ association that “the official policy of the NHL is one of inclusion on the ice, in our locker rooms and in the stands."

During my time with the Bengals, three players came across my radar at different times as the subject of significant insider scuttlebutt about being gay. In one case, I know from personal discussions that top club management was very aware. I never personally discussed these cases with any players, but it’s inconceivable to me this never reached the roster as a whole.

And I was pleasantly surprised to observe that each of the allegedly closeted trio seemed fully accepted at all times in the traditional solidarity of teammates. When one of them had off-field legal issues, unrelated to sexual identity, leading to some controversial reporting by a local TV station, several players reacted with near-rage at station personnel and demanded to me that the station be kicked out of the locker room.

In 23 years as PR director, I never saw a more angry reaction to media in defense of a teammate.

But still, we’re stuck at 1) Collins and 2) Nobody Else.

For thoughts on this from an active Big Four player, I sought out a Bengals player who I judge to be among the more thoughtful and free-speaking members of the team. And to use Collins’ word, I found his comments “disappointing.” He was willing to speak only if I agreed not to use his name, and his words were a hodgepodge of attempted inclusiveness mixed with ancient fears.

There was this: “I can take a guess at why — just fear of people’s reaction and in general society, not just sports. What your loved ones may or may not think. And the next fear is how teammates may or may not receive you. It’s something everyone doesn’t accept, even though we’re more accepting than at some time before, and it’s still not to where everybody feels comfortable with it. And in sports, ever since we’ve been little, we’ve been told to ‘eliminate distractions.’ ”

And this: “I don’t think it would affect my play. Once the game starts, everyone has to have a single focus. But what it could affect is the dynamics of the locker room, the closeness and connection. The brotherhood type of mentality. It would be different in the showers. You may say it shouldn’t be. I hear you, I understand that. But no one likes the idea of potentially being sexualized, of being ‘checked out.’ I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, but people are not comfortable with it.”

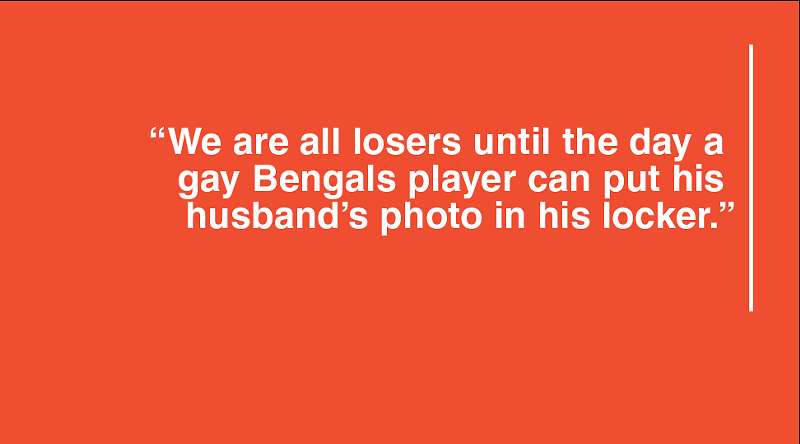

Thanks for the offering, anonymous Bengals pal, but I’m saying it is wrong. You may think you’re being protective of some special bond but the fact is we are all losers until the day a gay Bengals player can put his husband’s photo in his locker and talk about the romantic dinner they had on their anniversary. Until a Red’s husband can join other players’ loved ones in the family area at the game.

Until, even, the day Bengals’ boyfriends are welcomed without a single eye-roll at the luncheon Marvin Lewis hosts every September for players’ “significant others.”

In other words — until gays can play pro sports and live authentic lives, just like the straight guys do.

CONTACT JACK BRENNAN: [email protected]