Still in town for a short time after her recent graduation from University of Cincinnati with degrees in Africana studies and International Affairs, Édith Nkenganyi is trying to make every moment count for the outreach project she started here. She wants to get needed books into the hands of children from her native country, the central African nation of Cameroon.

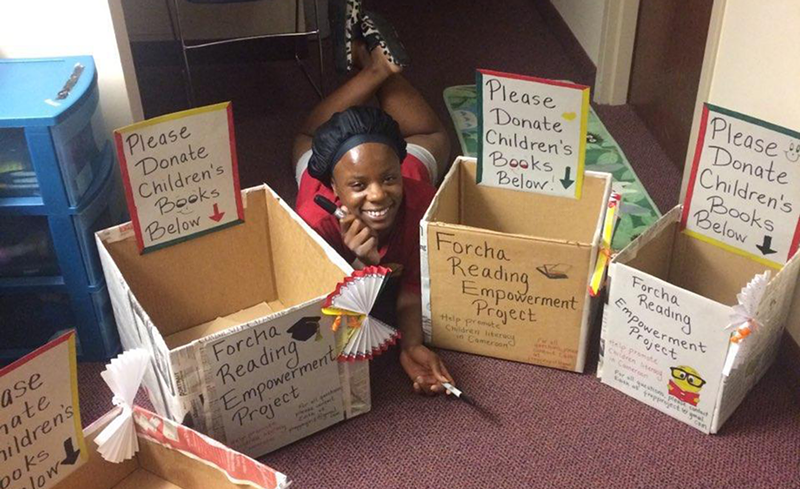

The effort is called the Forcha Reading Empowerment Project, named after her older brother who was robbed and murdered in Columbus in 2012, six years after Nkenganyi’s family came to the U.S. as refugees.

“It is important for children to have diverse books to read, because it exposes them to new ideas and expands their perspectives on life and the world,” Nkenganyi, 22, says. “I think reading also helps develop critical thinking and analysis skills.”

But there’s a problem — politics in Cameroon have been complicating her project. While she can get the books here via donations, and even has gotten some to Cameroon, she has not been able to get them used in schools.

Cameroon, Fontem village and the surrounding rural area in the Southwest Region have many English-speaking residents (like Nkenganyi, herself), but Cameroon’s history is complicated — the French and British divided up the former German colony after World War I. After both countries gave up their colonial empires, the two Cameroons united in 1961 as one country with two official languages: French and English. Because of discrimination of English-speaking citizens, Nkenganyi says, there has been tension. There has also been a separatist movement called the Ambazonia in the nation’s Anglophone regions, and she says the government has been responding to it violently.

Nkenganyi says one conflict point has been in the schools in her native Southern Cameroonian region, where people complained the French-provided teachers weren’t well-trained in English. Protestors shut down the schools in 2016. But they’ve never reopened, she says, because the nation’s president never responded to their demands.

“There’s a need for the children to get the books and education,” she says.

Nkenganyi knows the kind of enriching children’s books she wants to send — examples are The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, The Magic Treehouse Series by Mary Pope Osborne and Sal Murdocca and Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti, by Gerald McDermott, which is based on a folktale from the Ashanti people of Ghana. Dictionaries and history books are helpful, too.

Her passion to help others through this project started during a low point in her own life. In Columbus, she experienced the death of her brother just a few days before his 18th birthday. Only a few years younger than her brother, Nkenganyi was heartbroken.

It has been a long and difficult route, but Nkenganyi found her way to the University of Cincinnati. Here, she decided to start her book program, partly to honor her brother. Her friends from UC’s Racial Awareness Program (RAPP) helped her set up boxes around campus for people to drop books. Brice Mickey, RAPP’s director, says he was impressed with the global perspective she brought to the program.

“Her drive (and) determination were fascinating,” he says. “She is well beyond (her) peer group in that regard.”

Nkenganyi also has an arrangement with the Worthington Public Library, near Columbus, and others to receive unsold children’s books from the library’s book sale.

Nkenganyi has already shipped four boxes of books and school supplies to Cameroon. However, she says, with schools closed, those boxes have remained unopened. With more than 500 additional books stored in her mom’s apartment, she is trying to find other avenues to make sure the children get to read. That may mean tracking down officials with the separatist movement to help her with her mission.

But these problems are not stopping her — Nkenganyi is continuing to look forward to the day they will be read.

“I do believe a complicated decision is going to be made and the schools will again open,” she says. “And they will need resources since the students have needs since they closed the school.”

For more information on the Forcha Reading Empowerment Project, email [email protected]