The 2018 FotoFocus Biennial theme of “Open Archive” speaks to the desire to organize and make sense of a growing visual catalog, but artistic director Kevin Moore appreciates some fluidity, too.

“In photography, I always like subjects that are a little bit messy,” he says. “I like a subject that kind of wants to fall apart and won’t behave as a proper art history subject.”

In choosing this year’s theme, he wasn’t concentrating on photographs stashed in boxes, but the free-use images that we access every day on the internet and keep on our smartphones.

“We’ve all become archivists,” he says.

A prompt like “open archive” conveniently opens up infinite questions. Who decides what is worth documenting and preserving? How do artists draw upon the past? Are the memories that we hold in our hearts truer than the pictures we hold in our hands? Can we trust everything we see, particularly in the digital age?

With more than 90 exhibits and events across Greater Cincinnati, Dayton and Columbus, the fourth FotoFocus Biennial explores photography’s historical and contemporary archives from multiple angles. Though some shows opened weeks ago, programming this weekend officially kicks off a packed month, and some exhibits continue into 2019. The lineup’s biggest names include filmmaker/artist/writer Miranda July, late photographers Berenice Abbott and Eugène Atget, and British artist and Turner Prize winner Gillian Wearing, who speaks at the Cincinnati Art Museum Wednesday, Oct. 3.

This is Moore’s third FotoFocus. The New York-based art historian and curator says he appreciates that the biennial’s democratic structure gives organizers freedom to create programming that will attract diverse audiences.

Guest curator C. Jacqueline Wood of the Mini Microcinema is hosting a month of screenings tied to the archive theme. Some are dedicated to the influence of filmmaker July’s Joanie 4 Jackie project, a video chain letter of work by women filmmakers from 1995 to 2003. There’s also a series of films that use found footage as a visual source. Another presentation highlights the relationship between still photos and moving images. Other films archive the stories of makers. In Through the Lens of Time, for example, local photographer Ann Segal turns the camera on herself.

At the Contemporary Arts Center, all floors are devoted to FotoFocus for the first time. No Two Alike: Karl Blossfeldt, Francis Bruguière and Thomas Ruff opened Sept. 21 and juxtaposes modernist photographs from the 1920s with abstractions by the contemporary artist Ruff. Moore says the show, arranged by guest curator Ulrike Meyer Stump of Zurich, Switzerland will appeal to those who are studious about photography.

Two more shows open at the center Friday. CAC curator Steven Matijcio has brought in Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari, who collects and protects images from the Arab world and makes new art from them in The Fold — Space, time and the image. Moore, meanwhile, introduces a painter into the lens-based biennial with Memory Banks by Mamma Andersson, a Swedish artist who uses books and photographs as inspiration and subject matter.

And for the rest of October the CAC’s lower level will remain covered with photographs from Raquel André’s A Collection of Lovers. André, a Portuguese-born artist who performed early last month in the CAC’s Black Box series, uses a camera to document one-on-one meetings with strangers (a total of 167 as of August). But in an email she says she also considers her body to be “an archive of experiments bigger and more complex than what my memory can keep.”

That description also could apply to the near-impossibility of seeing everything FotoFocus is offering in more than 80 locations. Besides museums and galleries, installations are also in places like downtown storefronts, libraries, Ruth’s Parkside Café, Washington Park and the Academy of World Languages’ REFUGE/Health Hub in Evanston, where ArtWorks apprentices created an archive about the center’s multicultural families and neighborhood residents.

“We get to do two things at opposite ends of the spectrum,” Moore says. “One is to do really high-quality photography shows that could be shown in New York or San Francisco or anywhere — they’re of that level. And then we get to encourage things like schoolchildren going out in the community and doing photography. I like that it can be that high and that low at the same time. For me, photography is the breadth of all those things. It’s not an either/or thing.”

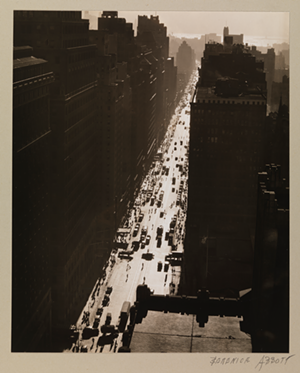

He chuckles during a phone interview over the ambiguity within the exhibit he has curated at the Taft Museum of Art; Paris to New York: Photographs by Eugène Atget and Berenice Abbott opens to the public Saturday. Were these two, who each became known for taking pictures of a city’s architecture during a period of transformation, art photographers or something else?

The Ohio-born Abbott was just starting out in the mid-1920s when she met the aged Atget in Paris while working as an assistant to Man Ray. Atget’s dreamy images of the old city’s streets, buildings and window mannequins were popular with painters, particularly surrealists, but he did not achieve wide recognition before his death in 1927. It was Abbott who brought attention to his work after she purchased his archive and returned to New York, where she printed his negatives and began photographing the city’s streets in his mode before turning her camera up at skyscrapers and establishing her own style.

Moore calls Abbott, who died in 1991, a heroine in “a very interesting human story” about two people recognizing the importance of systematically creating a record of a place and its people.

“It’s OK to think of them as art photographers, and also as something else, as historians — as architectural historians, urban historians or social historians. They could be all of those things at once,” Moore says. “It’s OK to think of them that way — it’s also more correct to think of them that way. Photography was a tool, they happened to be very good at it, and I’m glad they’re recognized for being art photographers. But I think both of them always felt a little bit uncomfortable with that terminology.”

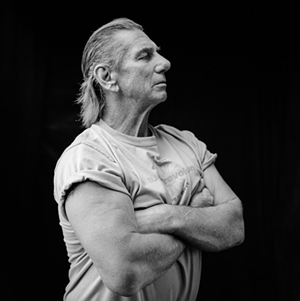

We see current examples of social scientists and urban historians with cameras in FotoFocus shows like Michael Wilson’s They Knew Not My Name, and I Knew Not Their Faces, at the Main Library. The local photographer known for album covers of Lyle Lovett, Jason Isbell and others set up a portable studio on city sidewalks and humbly asked strangers for the gift of sitting for a portrait. Kids, senior citizens, people of various racial and ethnic backgrounds, a person with a disability — all are treated equally as part of the fabric of Cincinnati. The library is also hosting Panorama of Progress: 170 years of Cincinnati’s Skyline and Photographic Technology, in which contemporary photographers revisit a scene captured in 1848. At Wave Pool, the group show Social Medium is subtitled Photography as a Tool for Community Collaboration, with projects that engage the gallery’s home neighborhood of Camp Washington.

The Mini Microcinema’s Wood is one of the Wave Pool artists. She’s also embracing the independent spirit on a bigger scale at her experimental cinema and by inviting filmmaker July to speak Sunday at the Woodward Theater.

This is the first time FotoFocus has added guest curators. Wood says helping produce the Open Archive biennial aligns with her own art practice, “where film and video and lens-based work kind of clashes between the cinema and the white cube of the art world.”

The Mini, which she started in 2015 through a People’s Liberty grant, has always been about helping others find their voice, she says. Though Wood has not yet met July, she’s felt a kinship ever since learning about her project Joanie 4 Jackie in grad school, a collection of video work by women across the U.S.

“It was this wonderful distribution system for women filmmakers to find a voice and find a way to show their work, in a time when the internet wasn’t influential yet in that way,” Wood says.

July turned the Joanie 4 Jackie collection of some 300 videos over to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in 2017. Speaking by phone from L.A. last month while editing her latest film, July said creating an archive of female-made short films and newsletters was on her mind from the start.

“I had a theory: Whatever is archived is remembered and therefore can be part of history,” she says. The things left out of history are marginalized.

July accepted all videos, and returned a compilation of 10 movies to senders, including their own. “The idea was that I couldn’t judge why any woman had made a movie,” she says. “I thought, ‘Well, what if a woman was making this just to save her life in that particular moment? She was very depressed and she just needed to make something.’ Wouldn’t that expression, even if it wasn’t quote/unquote ‘good,’ be valuable?”

July, whose 2005 debut feature Me and You and Everyone We Know took the Caméra d’Or at Cannes and was a winner at Sundance, considers the Joanie 4 Jackie project her film school.

“I wouldn’t have been able to make that feature if I hadn’t created that context for myself,” she says.

In the world of Joanie 4 Jackie, July didn’t feel obscure or like a minority. More than 20 years after starting the archive, she wishes things would be radically different in the mainstream.

“Young people are always still looking for a way forward,” she says. “They are on their own path, and this is hopefully some clue.”

Artist Wearing is another creative who uses an archive to feel connected to other makers, though in a more transcendental way; she uses elaborate masks and costumes for self-portraits in which she inhabits the personas of artists she considers to be members of her spiritual family. She’ll debut three such works at the Cincinnati Art Museum in Life: Gillian Wearing, which opens to the public Friday.

New pictures of Wearing as Albrecht Dürer, Marcel Duchamp (and his female alter ego Rrose Sélavy) and Georgia O’Keeffe are hung with a 2014 work, “Me as an Artist in 1984.” The latter is based on a family photo from a moment when she started to consider the real possibility of an art career.

Nathaniel M. Stein, the museum’s associate curator of photography and organizer of this exhibit, considers Wearing an anthropologist in search of secrets as she explores tensions between public and private life. “She will look at herself with as much scrutiny as she does others,” he says.

Unlike the artist Cindy Sherman, who also photographs herself in various guises, Wearing is not saying, “There is no there there,” according to Stein.

“She’s more interested in what makes you tick,” he says. “How does being you work for you? How do you shape who you are in relationship to the world?”

A fourth new piece, titled “Wearing, Gillian,” is a five-minute video featuring actors speaking about identity as if they were the artist, each wearing a version of her face. Wearing created the installation with the ad firm Wieden+Kennedy, and Stein calls its use of artificial intelligence technology groundbreaking.

Wearing’s art stays with the viewer, Stein says, and meanings unfold over time. “It’s like a little wedge that she drives into whatever it is you think you know about how you perceive other people and how you understand yourself,” he says.

Photography is the medium of contemporary life, Stein says, even if people don’t always respect it as an art medium because they’re overwhelmed by the images on various screens.

FotoFocus, he says, sorts through the clutter of the open archive and says, “Let’s stop, let’s think about this, because there is something important here.”

The FotoFocus Biennial 2018 begins this weekend. Passports for admission to fee-charging venues during FotoFocus are $25. More info: fotofocusbiennial.org.

10 More Shows to Check Out

The dozens of events at focusfocusbiennial.org may seem overwhelming. In addition to the marquee exhibits at the Cincinnati Art Museum, Taft Museum of Art and Contemporary Arts Center, here are suggestions for your archive:

Forealism Tribe: The Forealism Files — “Interdimensional travelers” document their time on Earth. Large-format portraits bring smiles as these performance artists survey everything from beaches to traffic barrels. Now open; closing date TBD. The Carnegie, 1028 Scott Blvd., Covington.

Finding Kenyon Barr: Exploring Photographs of Cincinnati’s Lost Lower West End — Here’s a second chance if you missed this exhibit’s debut in 2017. Rediscovered photos document vibrant street life in an African-American neighborhood that was razed for redevelopment in the late 1950s. Through Oct. 23. DAAP Galleries: Meyers Gallery, 2624 Clifton Ave., University of Cincinnati, Clifton.

Melvin Grier: Clothes Encounter — The Cincinnati Post photojournalist covered news and sports worldwide. Lesser known is his fascination with fashion photography, which he calls an opportunity to create a picture, not just take one. Through Nov. 4. Behringer-Crawford Museum, 1600 Montague Road, Covington.

Wing Young Huie: We are the Other — Pictures reflect the cultural complexities of America and provide a collective portrait of the “them” that is really “us.” Through Nov. 10. Kennedy Heights Arts Center, 6546 Montgomery Road, Kennedy Heights.

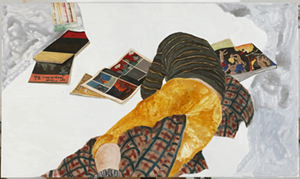

Wide Angle: Photography Out of Bounds — FotoFocus Deputy Director Carissa Barnard brings together 20 multimedia artists who test the boundaries of photography through collage. Names include Jimmy Baker, Harry Callahan, Sol LeWitt, Rick Mallette, Marilyn Minter, Robert Rauschenberg and Sheida Soleimani. Through Nov. 18. Weston Art Gallery, 650 Walnut St., Downtown.

Arbus, Frank, Penn: Masters of Post-War American Photography —When Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and Irving Penn turned their cameras on the overlooked and ostracized. Through Nov. 30. Pyramid Hill Sculpture Park & Museum, 1763 Hamilton-Cleves Road, Hamilton.

New American Stories — Refugees from Bhutan, the Dominican Republic and elsewhere create family albums and narratives about their new homes. Through Nov. 30. Prairie, 4035 Hamilton Ave., Northside.

Teju Cole and Vijay Iyer: Blind Spot — Writer/photographer Cole and composer Iyer join for a performance addressing moments when humanity has failed to respond to injustice. 5-6:30 p.m. Oct. 6. Memorial Hall, 1225 Elm St., Over-the-Rhine.

Peter Moore: The New York Avant-Garde 1960s and ’70s — Moore, who died in 1993, documented a pivotal period when music, dance and visual art intersected in radical ways. Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik and cellist Charlotte Moorman are part of his archive. Oct. 12-Dec. 22. Carl Solway Gallery, 424 Findlay St., West End.

Muse: Mickalene Thomas Photographs — The contemporary multimedia artist draws inspiration from 1970s black-is-beautiful imagery as well as traditional Western paintings to create works addressing femininity, race and beauty in the context of personal histories. Oct. 20-Jan. 13, 2019. Dayton Art Institute, 456 Belmont Park N., Dayton.

Behind the Mask with Gillian Wearing

British artist Gillian Wearing, who is known for taking self-portraits while donning masks of artists, relatives and her younger self, visits the Cincinnati Art Museum on Wednesday, Oct. 3 for a talk with Nathaniel M. Stein, associate curator of photography. She will receive the museum’s Schiele Prize, honoring the legacy of Cincinnati artist Marjorie Schiele.

Before Friday’s official opening of Life: Gillian Wearing, which includes four world-premiere works, the artist agreed to answer CityBeat’s questions via email. The exchange has been edited for space and clarity.

CityBeat: The video work you’ll be debuting, “Wearing, Gillian,” employs artificial intelligence software. Where do you see fine art going with AI technology?

Gillian Wearing: It is interesting and strange and connects to my work with masks of other people. I think any technology where you can explore the notion of identity is going to be fascinating, and can be used as a tool for empathy, understanding, etc. The flipside is that technologies can be used recklessly and inappropriately, and we won’t be able to avoid it being in all our lives for better or worse. My work isn’t about the tech aspects, but how I can explore ideas of who we are and use this as a really interesting tool.

CB: Have you found that women more often are wearing a daily mask they’d like to shed? Is contemporary media, including reality television, affecting how all of us — women and men — present ourselves?

GW: Women have been more historically associated with masks through makeup, clothes, etc. But essentially everyone presents different faces in different circumstances. I think social media has made people realize the power of editing their own lives, but when you look at a lot of this en masse, you can see a lot of similar shapes in people’s online narratives. It becomes like a social mask, it hides some of the harsh realities of life. If we see something that works, we copy it. I would say reality TV is different, as it tries to expose some of those things people try to hide about themselves, and the popularity of watching this is that we do seek truth in others but want to show a better side of ourselves to the world. We have many selves. It’s trying to accept these complex opposites in us which is the hardest part of life.

CB: What did you learn when “inhabiting” archival images of your relatives?

GW: It was seeing them as individuals not there for my needs. It’s hard to separate yourself from that. So becoming them before I was born, I was able to not think of me in that equation of what they did or didn’t do for me, and realize their own vulnerabilities, hopes and what were their needs from their parents. It gets complicated, as it should be.

CB: Which do you trust as a more accurate archive: personal memories or photos?

GW: All memory is selective and biased to how we are feeling, our emotions, our relationship to the object or person we are recalling. Photographs help anchor a certain moment in time, but it is fleeting. I cannot remember moments that happen before or after a photograph is taken, but I can get a sense of location, of what the environment I lived in was like. Without a photograph, people I have met in the past can disappear from my memory.

Life: Gillian Wearing is open for a preview 5-9 p.m. Oct. 3 at the Cincinnati Art Museum (953 Eden Park Drive, Mount Adams) featuring a conversation with the artist at 7 p.m. Reservations required; $10, free members, students and holders of $25 FotoFocus passport. Life opens to public Oct. 5 and is on view through Dec. 30. More info: cincinnatiartmuseum.org/wearing.