M

y dream is to see some new museums — maybe even one right here in Cincinnati — devoted just to video art.

I’ve mentioned this before to arts professionals, including curators, and have heard the reasons against: video art is an integral part of the contemporary-art world and shouldn’t be separated; it’s an offshoot of photography, which itself has a long history of being collected and displayed by art museums; and as artists use video/digital/virtual imagery/time-based elements with other media, old and new, there is no such thing as pure “video art.”

Good points, all. And yet so often when I watch video art in a gallery or museum not exclusively dedicated for it, I find problems. If the institution has set up a dedicated space for it, it’s often too small, allows for too much light or lacks good seating. If the works are just out there in close proximity to each other or to non-video work (and especially if they have sound), they can be distracting and even annoying. You quickly wind up with sensory overload. I so often feel like the surroundings detract me from spending the time with these works that they deserve.

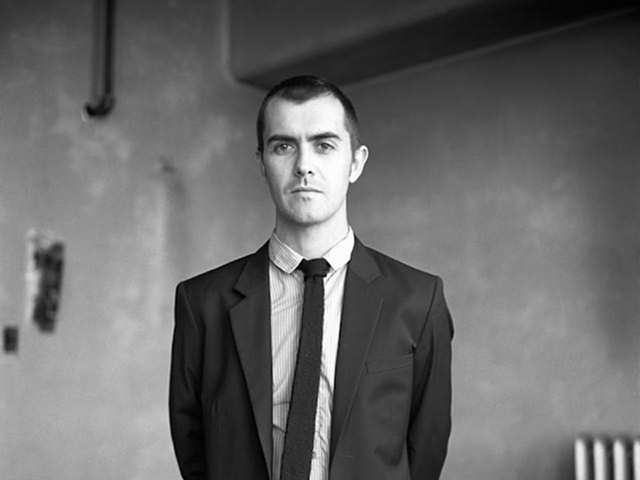

Jordan Tate, who teaches photography and Internet art at UC’s College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning and who co-curated the Contemporary Art Center’s current Is This Thing On? video-art show, has some of the same complaints.

“A lot of video-art survey exhibitions are too frenetic and overwhelming — with sound bleed and light bleed,” he says.

He’s hoping Is This Thing On? avoids that problem. Installed on CAC’s second floor, the show features two disparate areas of the gallery, front and back, where relatively short videos by 10 international artists, projected big, are played in continuous loops. (In between are monitors where guests can don headphones and watch smaller versions of those same videos in any order.) “When you’re in the gallery and want to watch a large projection, it’s the only thing there you can look at,” Tate says. “There’s really something nice about the forced consideration.”

He definitely has a point here. I spent much longer with the videos than I normally do, because the environment was so enveloping. With the right conditions for watching, you realize the brilliance behind something as seemingly primitive as William Wegman’s

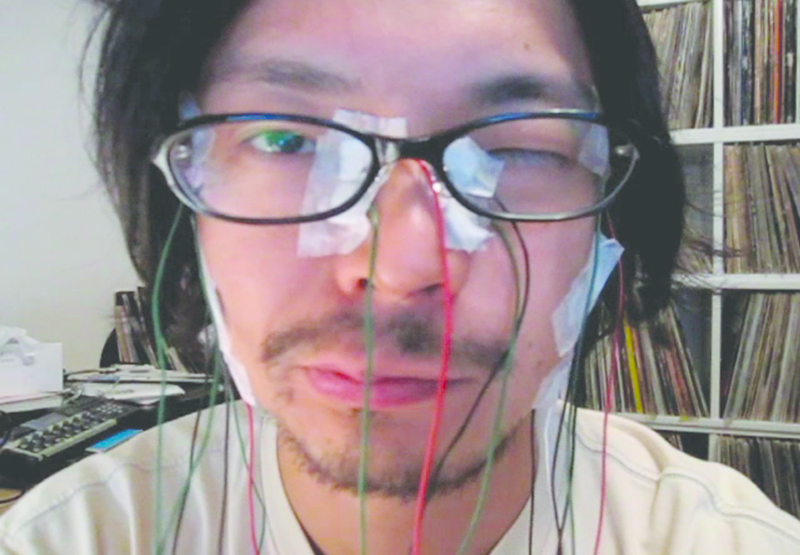

black-and-white “Astronaut” from the early 1970s. (This was done before Wegman became famous for wry photographs of his weimaraners.) A shaky camera looks at its subject (Wegman), and you can hear someone blathering. Then, the camera is still but the subject shakes about. It really creates the low-budget illusion of a spaceman reentering gravity, in a way that’s humorously clever.

Indeed, most of the videos are short and humorous, although sometimes in an odd, weird away. Another entry, by Greg Stimac, records the process of vehicles “peeling out” — revving up, screeching and laying rubber, sometimes while people watch. Another, by Pascual Sisto, follows a white plastic chair as it jumps and lurches around. The title of

the video is “No Strings Attached.” Tate says that’s meant to be ironic.

The videos being screened focus on the act of performance. For most, the performer is the artist. But as “Peeling Out” and “No Strings Attached” show, the actual performer can

be implied — or, I guess, can be a chair. In one of the newest videos, from 2010, Jeremy Bailey walks down a street juggling a purely virtual (computer-generated) public sculpture that looks perfectly integrated into his movements and environment. It’s an enchanting sleight of hand, augmented by his goofy personality.

Then there is the sheer, haunting mystery of Cheryl

Donegan’s beautiful “Practisse” from 1994, in which the artist creates face paintings by applying paint first to a cellophane hood and then to a glass pane in front of her. Figuring out how the video-recorded activity switches from active to passive, so to speak — when the paint clings to her features and when there’s a barrier between its swirls and her — is mesmerizing.

Tate and Aaron Walker, who has been involved with several alternative galleries and ran CAC’s 44 series, originally conceived of a BYOB (“Bring Your Own Beamer”) video night, in which locals could all bring their videos to the arts center and project them simultaneously. That occurred Nov. 4. The CAC’s director/chief curator, Raphaela Platow, suggested an accompanying gallery program that could swap out videos during its duration.

Thus, Is This Thing On? occurs in three phases. According to the CAC’s website, “Screen Test,” which emphasizes performance, will be followed on Dec. 19 by “Quality Control,” which showcases the changing role of technology and new media trends. The final phase, “New Forms,” opens Feb. 11 and considers the future.

While it might not be evident from “Screen Test,” which features pronounced work recorded by video cameras and webcam, Is This Thing On? will eventually move toward work created almost entirely via computer. It will also feature video sculpture, where the virtual image becomes just a visual element in something larger and three-dimensional.

So “Screen Test” becomes an enjoyable entry — a portal — into the wide world of new media.

But, hopefully, later phases will remain as much fun as “Screen Test.”

“Jordan and I feel that video work is sometimes seen as difficult to watch and interact with,” Walker says via email. “We specifically chose works that employed a self-aware humor. … There’s a playfulness to these works, a humor in addressing the everyday.” ©

IS THIS THING ON?’s rotating installments will be on view at the CAC through February 2012. For more information, visit www.contemporaryartscenter.org.