For a world-class museum, Greater Cincinnati’s Vent Haven Museum attracts precious few visitors — about 900 to 1,200 a year. How to increase attendance is problematic since it raises the issue of what kind of place Vent Haven is meant to be.

It's the only major public museum devoted to ventriloquism (the art of throwing voices) and has more than 750 historic and/or unusual ventriloquial figures — colloquially and sometimes controversially known as “dummies.”

While it risks cliché to say this, the museum can legitimately be tagged a unique experience because of that. It regularly gets international attention. The New York Times last month did a major feature praising it (as well as another hard-to-see Greater Cincinnati museum, the American Sign Museum). National Public Radio has also featured it, and a Web site called Internationaltraveler.com listed it as one of the world’s 10 weirdest museums.

But is that all Vent Haven is? Among those who know of it, many just consider it a resource for the offbeat or “weird” topic of ventriloquial history — “weird” because of the way contemporary entertainment sometimes has imagined the ventriloquists as troubled persons and the figures as having minds (and lives) of their own. There is a famous 1962 Twilight Zone episode, “The Dummy,” that helped create this impression.

Yet Vent Haven could hold potential interest as an art museum, a pop-culture/entertainment-history museum or an institution that uses its narrow subject as a way to tell the story of American social and political history. But Vent Haven’s site and crowd-capacity limitations hold down local visibility, outreach and attendance to the nonprofit museum, which occupies several secondary buildings at the Fort Mitchell, Ky., residence of the late ventriloquism enthusiast and businessman William Shakespeare Berger. It is on a residential street. (Berger’s actual house is not open to the public.)

“There’s no question if this was in an area with a lot of foot traffic and in a tourist-oriented place, I think you’d easily have 300 people a day through the museum,” says Tom Ladshaw, a professional ventriloquist/magician who serves on Vent Haven’s board of advisors. “But this was W.S.’s house, and this was essentially the way he set it up.” Jennifer Dawson, in her first year as Vent Haven’s curator, acknowledges some ventriloquists have said they’d love to have the collection in their hometowns.

“We know we would not be allowed to add another building to the property — there would not be room, anyway,” Dawson says. “Since it is a residential street, there are a lot of restrictions. Mr. Berger created this whole unique museum and had it started here. At this point we have enough space to continue housing the donations we receive.”

Starting Wednesday and lasting through Saturday, Vent Haven is having its “high season.” That is when the 31st annual ConVENTion of nearly 400 ventriloquists comes to Fort Mitchell. Titled “The Year of Creativity,” featuring a lecture by ventriloquist Jeff Dunham, it mostly occurs at a nearby hotel. According to a note by the convention’s Executive Director Mark Wade posted on the Vent Haven Web site (www.venthaven.com), attendance will be greater than last year, despite the economy.

“We don’t choose to participate in the Recession, thank you,” he writes. That makes sense, since ventriloquism in general is on an upswing. Recently, ventriloquist Terry Fator won the “America’s Got Talent” reality-show contest, taking home $1 million for his effort. Almost 14 million people watched the season finale. That’s a return to the golden-era old days of the TV variety (and children’s) shows, when Edgar Bergen, Senior Wences, Paul Winchell, Jimmy Nelson and Shari Lewis were popular ventriloquists.

Bergen in his heyday was as big a name in entertainment as Gene Autry or Walt Disney. Remarkably, in the 1930s, Bergen was hugely popular in radio with his Charlie McCarthy and Mortimer Snerd figures.

This year’s Vent Haven conventioneers will see a new gift: Jay Johnson, who played ventriloquist Chuck Campbell on Soap and went on to win a 2007 Tony Award for his Broadway show, The Two and Only, has donated a collection. It will be on display for the first time for the convention and will mark a modest but permanent expansion of Vent Haven’s display space.

“That will be a new addition and we’re going to use our fourth building to display that material,” Dawson says. “And Jay Johnson is going to be at the convention.”

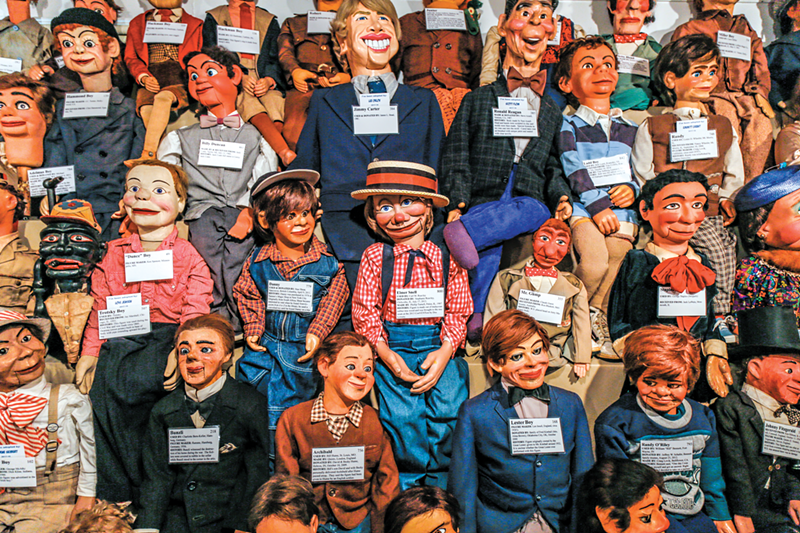

(Vent Haven will be closed to the public through July 22.) Once conventioneers are gone, Vent Haven returns to its quiet, appointment-only existence, although it has been working to improve its Web site with stories behind “featured figures.” Those lucky enough to get in for the remainder of this year will have the opportunity to be awestruck by Vent Haven’s piece de resistance: a building known as “the schoolroom,” where rows and rows of figures sit in metal chairs, organized according to their makers, with each exuding its own personality because of size, facial expressions, clothing or name. It’s as if each one’s past, and the fascinating story that goes with it, has been forever preserved in the present. The effect is overwhelming.

At Vent Haven, all the figures have fascinating back stories to tell — Jacko, the monkey with the moving eyes; Joe Flip, who quipped in a Brooklyn accent while his vent Dick Bruno spoke with a sophisticated French accent; and the lightweight Jane Jones, who was used by a rare female ventriloquist who herself weighed but 85 pounds. Vent Haven also treats the figure makers as artists in their own right and has done much work to give, say, George and Glenn McElroy of Harrison, Ohio, their due for creating figures capable of complex and imaginative facial movements.

The museum additionally has memorabilia, photographs, artifacts and an extensive collection of research books, such as a rare single-volume copy of the first book written about ventriloquism, from 1772. Another book, A Dummy Goes to Africa, is a memoir by a missionary/ventriloquist.

Some might say Vent Haven’s collection is hardly an artistic attraction in the way Monet and Rembrandt paintings are. But this subject matter might be the very reason Vent Haven could have far more impact on the city’s — and nation’s — museum world if it could accommodate more visitors, for ventriloquial figures occupy a place of strong ongoing fascination within the art world.

The artist/photographer/filmmaker Laurie Simmons, whose 40-minute movie The Music of Regret features the figures and Meryl Streep, worked with the Vent Haven collection on her still photographs and films beginning in 1987. Some of the results have been collected in the book Walking Talking Lying: Laurie Simmons, in which author Kate Linker quotes Simmons as saying, “So many kinds of male relationships come up between vent and dummy: paternal, buddy love, best-friend love, brotherly love, homosexual love.” The author also sees the potential for a veritable existential conflict in Simmons’ choice of subject matter — “the difference between its illusional humanity and its status as an object.”

Dennis Kiel, a former photography curator at Cincinnati Art Museum and now chief curator for Charlotte’s Light Factory Museum of Photography and Film, tried to pitch a Vent Haven show for CAM several years ago. The idea came after he saw the catalogue for a Simmons retrospective at Baltimore Art Museum. He said he received support from the museum’s costume curator.

“Initially, the idea was to show Laurie Simmons’ photos along with a selection of the actual dummies, etc., from Vent Haven,” Kiel writes in an e-mail message. “There are a few other photographers who have been allowed in there since … and I was thinking of including some of those images as well. But I liked the idea of focusing just on Laurie’s work and Vent Haven, especially since she had a dummy made of herself because of the experience. However, it never went any further. The idea was vetoed by two directors.”

Actually, a Cincinnati art museum did feature Vent Haven’s figures previously, but it was a long time ago: From Dec. 9, 1976, to Jan. 26, 1977, the Contemporary Arts Center offered Selections From the Permanent Collection of the Vent Haven Museum. It displayed 54 figures in a show credited by the then-director to assistant curator Karen S. Chambers and preparatory Frank Farmer.

And the art world’s interest continues. David Goldblatt’s 2005 book, Art and Ventriloquism, is but one example: “Like ventriloqual (an alternative spelling) dummies, artworks take on personalities, characters of their own, often saying what the artist herself would or could not say in voices distinct from her (our) daily modes of expression,” a published overview of the book explains. “Goldblatt uses ventriloquism as an apt metaphor to help understand a variety of art world phenomena — how the vocal vacillation between ventriloquist and dummy works is mimicked in the relationship of artist, artwork and audience, including the ways in which artworks are interpreted.”

Also, the stories of ventriloquists and their figures offer compelling glimpses into American social history — especially race relations. For instance, the PBS series History Detectives visited Vent Haven for a segment on John W. Cooper, a vaudeville-era (and later) African-American ventriloquist whose work defied all-too-common racial stereotyping in entertainment.

Evidence of such stereotyping, as well as the evolution of its end, can be found at Vent Haven. While the museum doesn’t have Cooper’s original figures, it owns photographs, a script, correspondence and a rare sound recording of his act. It also has the in-manyways-remarkable group of connected figures belonging to the early-20th-century blind ventriloquist Jules Vernon, who could operate them all at once. One is Happy, a smiling black man dressed in a red-and-gray uniform.

“Happy was a standard type, a character usually known as ‘the laughing Negro’ — it was actually listed in catalogues,” Ladshaw says. Moving to more contemporary times, the museum also has the original Lester, used by African-American ventriloquist Willie Tyler.

Should Vent Haven try to expand or move to a better location and try for growth? That depends on what its principals believe it should be. Berger set up Vent Haven as a charitable foundation to preserve and display his collection after his death in 1972. It opened in 1973. He is as much a reason for its existence as his collection. Besides being a successful businessman — president of Cincinnati’s Cambridge Tile Company — he was a “ventriloquarian,” actively collecting everything he could about the subject and buying whatever he could find on the market.

He was also an amateur ventriloquist who bought his first figure — Tommy Baloney, which is at Vent Haven — in 1910 and maintained correspondence and relationships with most of the nation’s key ventriloquists.

Because Berger lived there, the site has a folkloric aspect that Vent Haven wants to preserve. Berger was well known to the Hollywood entertainers who played Northern Kentucky’s supper clubs and gambling houses in their heyday.

“Edgar Bergen once came at 3 in the morning,” explains Vent Haven’s previous curator, Lisa Sweasy. “W.S. left word, ‘I don’t care what time it is, come to the house after the show.’ ” (Bergen was playing at the Lookout House.) So Berger-reverent is Vent Haven that visitors are asked to sign in because that’s a tradition Berger started in the 1930s.

“What is so great about this place is it would be unsurprising to me if he walked out that back door,” Sweasy says. “It is the same location and similar to how it looked in his lifetime. Things are pretty much as he left them. What we don’t want to do is erase him.” And in a way, the environment he created might be Vent Haven’s greatest claim to being an art museum.

“It was his own personal universe and the Vent Haven Museum exists as a monument to his own involvement as a folk artist in much the same way that Simon Rodia’s ‘Watts Towers’ testifies to his,” CAC’s Chambers wrote in the catalogue for her art show about this collection.

Vent Haven Museum is open for guided tours by appointment only from May through September. Call 859-341-0461 or e-mail [email protected]. Admission fee is a $5 donation.