As the crush of the Great Depression dragged on into 1939, the American Institute of Planners released a curious film simply called The City meant to screen at that year’s New York World’s Fair.

The striking collection of black-and-white footage sat at an odd intersection of documentary film, social commentary and borderline propaganda for one of the most radical experiments the United States government would ever undertake — the wholesale creation of entire self-sufficient (and racially-segregated) “greenbelt” towns ringed by forests and farmland and built around collectivist principles.

The federal government built one of those towns, called Greenhills, on a flat sweep of farmland 15 miles north of Cincinnati.

These New Deal towns were meant to provide work and housing for those struggling under the harshest economic calamity the country had ever seen. But they also aimed to provide a new way of living together for the white residents lucky enough to be selected as “pioneers” to settle there.

In its opening minutes, The City features swells of gentle, gliding strings underscoring scenes of rural splendor — village squares, water rushing over mills, children playing in a swimming hole. A man’s voice enters, extolling the simple, small-town life Americans led in the previous century.

Soon, the mood shifts. Anxious, discordant music with quick, stabbing horns accompanies a rush of smoking factories, tenements and lines of ramshackle houses in cities that look very much like Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Men and women trudge through a bleak, industrial landscape. Children forlornly peer out of windows. Cars endlessly wait in traffic, or careen into pedestrians, or sit mangled.

“Don’t tell us that this is the best you can do in building cities,” the voice intones. “Who built this place? What put us here and how do we get out of here again, we’re asking?”

The footage then transitions into a sequence of warm, peaceful images: boys riding bicycles through a sun-dappled landscape of tree-lined paths with simple, clean-lined structures around them. Children filing into a tall, pale building with simple, chiseled lines bearing the name “Greenhills Community Building.” Men and women working in sleek kitchens. Inhabitants tending gardens, having picnics and going fishing. All are white.

In the film’s closing minute, the smoke-filled cities and urgent music return to alternate with the gentle scenes of the idealized towns.

“You take your choice,” the voice says as the contrasting images flicker back and forth. “Each one is real. Each one is possible. Shall we sink deeper, sink deeper in old grooves, paying for blight with human misery? Or have we vision? Have we courage? Shall we build and rebuild our cities clean again, close to the earth, open to the sky? Can we afford a house, a neighborhood, a city as good as this for everyone? Maybe the question is, can we afford all this disorder?”

By the time The City was released, the escape from congested city life it advertised was more than a future-looking city planner’s fever dream. It was a brick-and-mortar, flesh-and-blood reality in three locations around the country, including Greenhills. But that dream — designed by a small cadre of advisors to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, executed by his recently-created Resettlement Administration and championed in its early years by first lady Eleanor — was also dead by 1939, declared unconstitutional by a federal court.

Eighty years later, Greenhills still exists, both in memory and reality, its International Style white buildings surrounded by now-mature trees planted in spots dictated by federal planners’ diagrams.

If you ask many of the early residents alive today, they can still paint you a picture of the early years.

They’ll tell you about the dozens of kids at play in epic war games in the forests and fields that ringed the peaceful, isolated town. About the hours spent under the sun at the local pool or at potlucks where everyone knew everyone. About the cooperatively owned grocery store. About Roy Rogers and Flash Gordon flickering on a screen above the golden-hued hardwood floor of the gym in that towering white community building that looked out from the center of town. About John Baldwin, the police chief who knew everyone’s name and who would personally find a lost child or direct traffic as students walked to school. About ice cream socials, fish fries fueled by the shared spoils of the great fishing in the neighboring lake and fireworks displays so large they shut down Winton Road, the main street running through town.

Jackie Noble’s parents moved to Greenhills the year it opened, 1938, when she was 2 years old. Save one brief interruption, she has lived there ever since. She relishes her memories of the community pool, of the close-knit bonds between her neighbors, and the sounds of playing children that have reverberated through the town for generations.

“I don’t know if Eleanor Roosevelt expected this or not,” Noble says as she sits in a coffee shop that was once the village bank. “But she had to sit back and think, ‘I did a good thing.’ Of course it worked. It’s still working. My granddaughter and great granddaughter are still living in the village. That’s five generations.”

For many original residents, the New Deal-era effort at Greenhills was a success.

But the legacy — and future — of the Ohio town born out of this radical experiment is cloudier today. The march of time and social conventions shed harsh light on the town’s segregated origins. And recent demolitions have leveled some of the town’s original buildings.

In some ways, the greenbelt towns — Greenhills; Greenbelt, Maryland outside Washington, D.C.; and Greendale, Wisconsin, outside Milwaukee — would presage the rapid suburbanization of many predominantly white, middle-class Americans in the coming decades. That development was privately undertaken, of course, but was also encouraged and in some cases subsidized by the federal government.

But in other ways, the towns exist in their own strange moment in time; one in which, for a brief few years, federal authorities flirted with openly collectivist goals even as they dictated that their futuristic utopias be racially exclusive.

Eight decades removed, the lessons of the greenbelt towns may still have some relevance as contemporary America rediscovers a love for walkability and urban green space in its cities and struggles with housing affordability, residential segregation and its fraught, complicated relationship with ideas and policies some would call socialist.

University of Cincinnati History Professor Julie Turner has researched Greenhills extensively and is working on a book about the village.

“We see in them a recognition by the federal government, or at least a small subset of planners, an acknowledgement that better housing alone wasn’t enough,” she says. “The towns specifically addressed many of the anxieties of the era between the World Wars: fears about urbanization, about the ‘machine age,’ about changing family dynamics and gender roles, etc. By providing things like movie theaters and swimming pools, the planners were consciously aiming to bring residents together in very neighborly ways, to avoid youth crime, and to bolster the idea of a traditional American way of life, even as they did so using new planning and architectural models.”

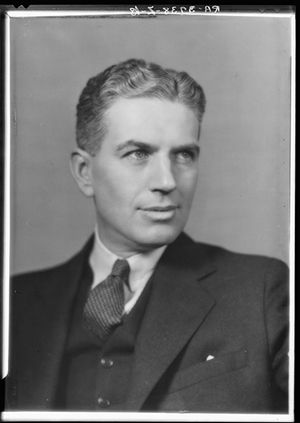

The ideas FDR advisor and Resettlement Administration head Rexford Tugwell marshaled together to launch the greenbelt initiative weren’t new.

The “garden cities” concept — suburbs designed in close proximity to green space as a balm for the increasingly sooty, congested urbanity of the Industrial Revolution — was originally the late 19th-century brainchild of British social theorist Ebenezer Howard. Howard’s concepts were never completely carried out, but a new generation of city planners carried the garden city torch into the 20th century, designing towns like Radburn, New Jersey and Letchworth in the United Kingdom.

Responding to the sweeping Depression, voters elected President Roosevelt in 1932 on his promises to address the nation’s deep economic malaise. As part of those efforts, Roosevelt created the Resettlement Administration in April 1935 via an executive order and put Tugwell, then a Columbia University economics professor, at the head.

“He definitely saw government intervention on behalf of the underprivileged as a legitimate federal power — not a common outlook at that time,” UC professor Turner says of Tugwell. “During the New Deal, he proposed the greenbelt idea to FDR as a way to put men to work building the towns, with the added bonus of slum clearance and the provision of good, low-cost housing for the working class.”

Tugwell, extensively-educated, dapperly dressed, confident and pugilistic, was a divisive figure. Critics called him a socialist and said his ideas were un-American. But, not one to shy away from ideological battles, he quickly pushed forward with the unprecedented greenbelt concept, and by 1936, construction of Greenhills and the other greenbelt towns was underway.

“My idea is to go just outside centers of population, pick up cheap land, build a whole community and entice people into it, then go back into the cities and tear down whole slums and make parks of them,” he said of the concept at the time, though the federal government wouldn’t begin slum clearance in earnest until much later.

The Resettlement Administration surveyed more than 100 prospective cities near which to establish greenbelt towns. The criteria: the cities must have some manufacturing, but more than one dominant industry. They also needed reliable, modern public transportation and had to be surrounded by cheap, abundant farmland. Cincinnati made a short list with four other cities, including St. Louis, which was later dropped from the program, and Trenton, New Jersey. A settlement there called Homestead was never finished to the scale envisioned by planners due to legal battles over the greenbelt concept.

After locking down locations, the federal government moved quickly. In what would become Greenhills, that meant snapping up 5,930 acres of land in a matter of months for the town, the greenbelt surrounding it, outlying farms and possible future developments.

Most farmers, suffering greatly during the Depression, quickly sold their plots. But not everyone was willing to go, Greenhills Historical Society’s Paul Richardson says. A farming family by the name of Bastion resisted federal advances to buy their land on the south side of what would become Greenhills.

“Mr. Bastion didn’t want anything to do with the government,” Richardson says. “He literally got his rifle out and shot at federal agents.”

Eventually, officials left him alone, and, though the land sold decades later and contains housing today, there’s a large notch missing from Greenhills as a result.

With much of the necessary land acquired, federal officials went to work building the town. Ohio native Justin Hartzog, who had previously designed parks for Cincinnati suburb Mariemont, was Greenhills’ chief planner. Tugwell himself visited the site, though there is no evidence Franklin or Eleanor Roosevelt set foot there.

While Tugwell toured the site in a suit and tie, those charged with the day-to-day construction lived a more rugged life.

Nick Bates, hired by the federal government to help oversee construction, is said to have lived in a tent in Mount Healthy and ridden a mule down Springdale Road into Greenhills every day to go to work. He later became the village’s maintenance supervisor and head of its volunteer fire department.

Eventually, the project required $11.5 million (roughly $210 million today) in federal investment and more than 3,000 workers putting in more than 4.3 million man hours.

By 1936, the same year work on the greenbelt towns launched, political pressures forced Tugwell from the Resettlement Administration. He would stay close to the president, eventually getting the nod to become the governor of Puerto Rico.

In the meantime, work continued on the towns.

Originally, Greenhills was to be home to 1,000 families. But due to budget cuts, it ended up with 676 units of housing — some sturdy brick, others frame houses.

By 1940, about 2,677 people lived in those government-constructed houses, Census data shows. All were carefully chosen by the Resettlement Administration.

That, too, was part of the experiment.

“The original intention was to make jobs,” Richardson says. “But the other intention that Tugwell had, interviewing all those people, was to start a neighborhood out of nothing. They were trying to create community. Of course, other towns like Mount Healthy are also communities, but here, the government was trying to create one from scratch.”

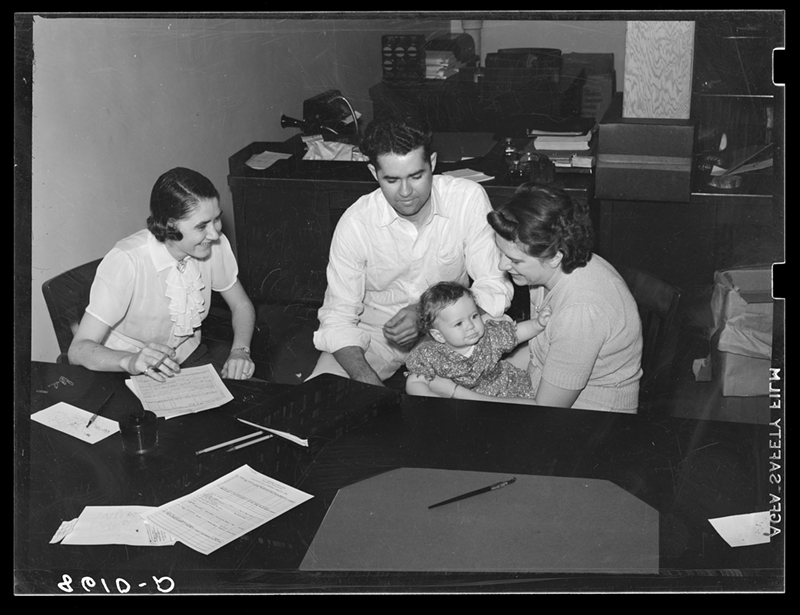

Potential residents had to fill out a 15-page application and were expected to be working class. Only families making between $1,000 and $2,000 a year were considered, and only white applicants were invited, a reflection of the racist political realities of the time.

UC professor Turner says there isn’t a lot of documentation on the issue, but that there are a number of clues that make it fairly clear why Greenhills ended up segregated.

“A general consensus among historians of these and other housing and town-building projects during the Depression suggests that it was already pushing the limits of many Americans’ political beliefs for the government to even be providing homes, and that integrating these residential areas would have pushed too many iffy supporters to oppose the programs entirely,” she says. “After all, even Cincinnati and Milwaukee were largely segregated at the time.”

The Self-Contained Utopia

But for many of those who were able to move to Greenhills, the government’s efforts were life-changing.

English professor Mary Ellen Seery’s parents moved to Greenhills in 1938 and she was born there in 1941. She left for college but returned in the early 1960s to live in the community for a few more years.

Seery’s parents were looking for a place to raise a family in the midst of the Depression. They had been living with Seery’s grandparents on Scioto Street in busy, cramped Corryville when their first daughter was born, forcing them to seek their own place. After a brief stint in a small, older apartment in North College Hill, they heard about Greenhills and applied.

The budding family landed on the list of accepted residents and soon moved into a brand-new house on Cromwell Street — part of what Greenhills residents call the “C-Block.”

“This was a godsend for a lot of people,” she says. “I think my family was very typical in that way. They were ecstatic they got on the list. They talked about that all their lives, how important it was at that point of their lives, during the Depression, for a young couple to move into a glorious place with all these other young couples. They made lots of friends in the community.”

The family found itself in another world, full of white-painted small apartment buildings cradled by a massive greenbelt and centered around the community building. It was affordable —about $28 a month for a two-bedroom apartment — and easy to get around.

Walking paths and narrow, pedestrian-friendly streets without four-way intersections curved gracefully through the heart of the town. Houses faced away from the street into more green spaces to encourage residents to meet each other there. Neighbors interacted easily, and with a cooperatively-owned grocery store, a drug store, doctors and dentists, there were few reasons to leave town except to go to work. While Greenhills didn’t have any churches at first, congregations held services in the gym of the community center, with Catholics wheeling an altar in and out of the space between masses.

Seery’s parents immediately fell in love with the place, eventually moving to a large four-bedroom house on Burnham Street in the B-Block with a huge yard that led straight into the greenbelt.

“They thought that was total heaven,” she says.

By the time Seery was born, the Depression had faded and a new struggle had risen to take its place — World War II. Even as a young child, the conflict and its attendant rationing, black out drills and pensive atmosphere left an impression on her and other early town residents, as it did on many Americans. The difference, however, was that Seery and her neighbors lived in a town built by the federal government and designed to foster a sense of tight-knit community.

“I remember lots of get-togethers and potlucking with other families,” she says. “Who has this? Who has that? And putting it all together in a communal way. It was this utopian existence superimposed with the war, where there was want and worry.”

The close-knit, idyllic feeling continued after the war and even beyond the federal government’s divestment from Greenhills in 1950, when Congress’ deep suspicions of such an avowedly collectivist endeavor finally caught up with the greenbelt towns. Residents were allowed to buy their houses from the government, and the recently-formed Greenhills Homeowners Corporation took control of the common spaces in the village.

Despite the change in ownership, day-to-day life in the town didn’t change much at first.

As smitten as Seery’s parents were with the community, they wanted her to experience the outside world. While other children in town went to Greenhills High School, then located in the community building, Seery’s mother sent her to Our Lady of Angels Catholic School in Saint Bernard.

“She didn’t want us to grow up any more in this isolated environment,” Seery says. “I learned about German bakeries, all of the bars my classmates’ parents owned, I got to meet girls from Saint Bernard, which is a whole other experience, and I got to know black students from the West End.”

Others stayed and attended Greenhills High School, deepening their ties to the town.

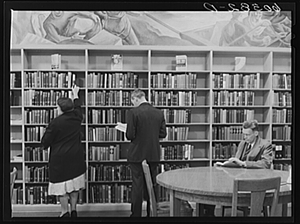

Bobbe Kugele sits in the former library of the community building and talks about its significance. She’s the head of the school’s alumni association, as well as an employee with what is now called Winton Woods School District, which serves Greenhills and neighboring Forest Park. Her family moved to Greenhills from Ludlow, Kentucky in 1941, and she was born there in 1945.

These days, the library is a museum dedicated to the town’s history, and the legacy of the New Deal-era Works Progress Administration permeates the space. The room is still ringed with a mural by locally-renowned WPA artist Richard Zoellner and contains a model kitchen with a 1930s-era stove and refrigerator.

“The room downstairs was my kindergarten classroom,” she says. “For me to look at this building, which is 80 years old, it’s beautiful. It means a lot. The folks who went to school here have a special bond. Some of my friends, they’re still close, whether they graduated in the ’40s, the ’50s or the ’60s.”

As if to illustrate her point, sitting next to Kugele is Larry Zettler, a fellow Greenhills High School alum born here in 1942. After leaving to serve in Vietnam, Zettler returned to Greenhills and was a police officer there from 1972 to 1996.

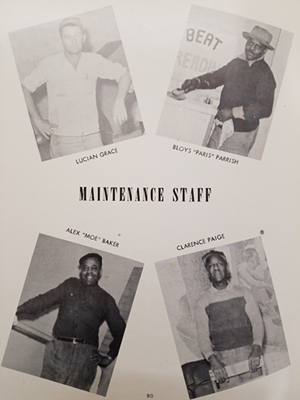

He also has fond memories of the school, including the janitors — the only black people many of the students encountered until they left town. Two, Bloys Parrish and Clarence Paige, left a particular impression on Zettler.

“I remember Parrish mopping up and down the hallways, singing while we played in the gym,” Zettler says. “It was a thing of beauty, listening to him sing. He was the nicest, most gentle man. So was Clarence. They were wonderful.”

A number of other students from that time remember the duo, especially Paige, who was also a saxophonist and Jazz bandleader. Paige would not have been permitted to live in Greenhills, which may have had so-called "sundown" laws, when he started working there and commuted every day to work from Cincinnati’s West End.

According to Cincinnati address directories, Paige lived on Mound and Charlotte streets when he worked at Greenhills from the late 1940s until he retired in the mid 1960s.

Earlier in his life, he led bands like Clarence Paige and His Syncopators and the Clarence Paige Orchestra, which was up to 10 pieces strong. His groups often appeared on local radio and played regularly at the Mariemont Inn, the Cotton Club and other well-regarded local clubs.

He also toured the region with other Jazz artists, including trumpet legend Bill Coleman, who in his memoir Trumpet Story recalled becoming interested in music around the same time as Paige when they were both growing up near Kenyon Street in the West End. The two also weathered racially-charged scrapes together as they toured West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio. According to Coleman, Paige’s band was one of the two most well-regarded among black musicians in Cincinnati.

After playing under Paige for a while, Coleman moved on to bigger national acts. He relocated permanently to France in 1948 to escape segregation, where he gained fame and eventually won the prestigious Ordre National du Mérite for distinguished contributions to cultural life.

Paige was still playing when he took his job at Greenhills, occasionally performing at school dances in the 1950s. He and Parrish were exceptions to Greenhills’ almost entirely white landscape.

“The thing is, those were the only black people I ever saw until I got my first job,” Kugele says. “See, that’s how it was here.”

Zettler agrees.

“Oh, me too, until I went into the Army. And was that the government, on purpose? I imagine so. That was the times we were in. They were good to the kids, though.”

Slow and Steady Changes

In 1963, as Zettler was serving in Vietnam and Kugele was getting her first job after graduating from Greenhills High School, big changes had started to come to the town’s cozy, sealed-in bubble.

Some were shocking and immediate.

Around 9:30 p.m. on a hot August evening that year, 15-year-old Greenhills High School student Patty Rebholz was walking home from a dance at the town’s American Legion Hall. She never made it. After a frenzied search, police found her at 5:30 a.m., strangled and beaten to death, in the backyard of a house across the street from where her boyfriend, 15-year-old Mike Wehrung, lived.

Wehrung was immediately a suspect, and after questioning him, police felt sure they had the killer. But a county juvenile court judge, Benjamin Schwartz, intervened, making Wehrung a ward of the state and sending him to military school in North Carolina.

The case became a national fixation, but remained unsolved for decades. Then-Hamilton County Prosecutor Mike Allen reopened the Rebholz case in 2000, and Wehrung stood trial for allegedly murdering his high school sweetheart. But a jury found him not guilty, in part due to a lost deposition from 1963 in which a witness placed Wehrung in his own living room at the time of the murder.

The case remains unsolved. Longtime residents like Zettler, who worked the case as a police officer when he returned from Vietnam, and Kugele, whose younger sister was very close friends with Rebholz, say it forever disrupted the calm, sealed-off atmosphere in Greenhills.

“It shook the community,” she says. “People started locking their doors then. My sister was in school at that time — she would say it wasn’t fun anymore. Someone’s been killed, brutally, viciously.”

Other shifts were more gradual: the development of new, single-family homes in Greenhills started in the 1950s and accelerated in the proceeding decades after the federal government sold the town.

“People used to say to us, ‘Hey, you live in those barracks,’ ” Kugele says of the original housing. “And maybe they did look like barracks. To have a single-family home… that had been few and far between. But then, they started building them on Drummond Street in the mid-1950s. My dad was pretty unhappy about that.”

The town narrowly avoided an even larger change in the intervening decade. After taking possession of the town’s common areas, the Greenhills Homeowners Corporation moved to open up the greenbelt — which now included a dam constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1950 to keep the Mill Creek Valley from flooding — to more housing development.

“The greenbelt was sacred,” Zettler says. “When it was sold to the GHOC, the condition was the government would sell it for one dollar, but it could never be developed. It had to remain a pristine greenbelt. As the village began to advance, GHOC started showing interest in developing into the greenbelt. And the government stepped in and said, ‘no, no.’ ”

The federal government fought GHOC’s plan all the way up to the Supreme Court, which finally ruled against developing the land in 1966.

Zettler sees both the upside and downside of that.

“It strangled the community in some ways,” he says. “We stayed constrained by the greenbelt.”

Even with the greenbelt around its edges intact, however, Greenhills was changing at its core.

“The supermarket, the drug store, they started changing hands,” Kugele says. “The store wasn’t a co-op anymore. In the early 1970s, the pharmacy changed ownership. That put a lot of people who had worked here for years out. My mom worked there for 25 or 30 years.”

The changes happened slowly, longtime residents like Kugele and Noble say. But the past few decades have brought a shift — more mobility, more outside noise, less feeling tied to a single, isolated place like Greenhills.

Noble, who still lives in Greenhills and rents some of the original housing she owns to young families, says the community is still intact, even if people aren’t bound to it in the same way they used to be.

There is still a tight-knit feeling here — during a recent windstorm that knocked out the power in Greenhills, the village opened up its town hall for anyone who needed to come in to charge cell phones, grab a snack or simply be around other people. Every year, the village Christmas celebration draws hundreds to the center of town for a massive bonfire, horse and buggy rides, tours of the community building and other events. And the shopping center continues to host a number of locally-owned businesses. But things have changed, too, Noble says.

“I still see a lot of the old times here,” she says. “But I don’t think there is the same openness that there used to be. How do you explain it? People aren’t as secluded out here now. We were secluded, we knew it, but we didn’t think about it that way.”

A Slow Walk Toward Diversity

By the mid-1960s, racial shifts were also taking place, albeit very slowly. The 1960 Census shows Greenhills with zero black residents, but a few trickled in and by 1970, when Greenhills’ population hit its peak of about 6,100 people, there were 10 people of color living there.

Seery, the English professor who grew up in Greenhills and moved back with her husband in 1965, remembers one of the community’s first black families moving into one of the community’s newer sections the following year.

“He was an engineer with GE,” she says of the father in the family. “There was terrible uproar about it at the time. They were threatened. A family prayer group I was in decided to be a support group for them and speak up for them. It became a big issue. I didn’t realize until that time how much prejudice there would be in the community. I still have these mixed feelings about this community that I loved and the people I knew and the lack of welcome for this family.”

Integration inched along over the next decade. By the 1970s, the NAACP had named Greenhills, along with a large number of other local districts, in legal action aimed at Cincinnati Public Schools around segregation. In 1978, the Greenhills-Forest Park School District drew up a voluntary plan (listed on page 39 of this document from the Department of Education) to integrate Greenhills High School with neighboring Forest Park High School, both of which were run jointly by the local school district.

The next year, more than 100 black students from Forest Park found themselves on buses bound for Greenhills.

Greenhills’ neighboring town had been privately developed after the federal government sold off excess land it bought when planning Greenhills, and over the years had become home to a sizable black population, including some displaced from Cincinnati’s West End during slum clearance programs in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Kathy Y. Wilson remembers the final day of eighth grade, when she and the other students who would be going to Greenhills were packed into the Forest Park Middle School gym and told the news. Most were not happy.

“Because we were 13-year-old adolescents who thought we were big time because we were leaving eighth grade, someone said something defiant about it, and it was like a ripple effect, we all started in,” she says. “But they gave us these letters for our parents, and I think they had had it all planned out, the bus routes and everything. It was a big deal.”

Despite her early trepidation, Wilson, who later became an award-winning journalist, columnist (for this publication and others), author and college educator at the University of Cincinnati, credits the experience with launching her career as a writer.

“They made a way for us,” she says. “They hired a black woman as an assistant principal. I feel like they bent over backward for us. Another black person might feel differently. But I thought it was the bomb. Because of my AP English teacher, I started studying transcendental meditation. She introduced me to Emerson and Thoreau. She introduced me to James Baldwin. Miss Arnold — I still give her credit for everything about my intellectual growth as a writer. Other than my mother, she was the first person to tell me, ‘Kathy Y. Wilson, you’re a writer. Don’t you know?’ ”

There were hard moments, including an incident in which a white student slammed a locker just above her head and called her a racial slur as he walked away and another in which a guidance counselor tried to dissuade Wilson, a straight-A student, from going to college. But overall, Wilson says she didn’t experience the racial tension at Greenhills she might have expected.

“It ignited me. It really did. And everything that goes along with it, even teaching, I think I got that from Greenhills,” she says. “Now, my experience could have been completely different if my father had been in a house in Greenhills. I can’t guarantee it would have been as welcoming. Busing is different than housing.”

The year after Wilson entered Greenhills High School, the Census counted 23 black residents among the roughly 5,000 people living in Greenhills. In the decades since, however, more have moved to the community.

By 1991, Greenhills High School and Forest Park High School merged, becoming Winton Woods. That merger saw its own, sometimes racially-charged growing pains, some say. It also removed one of the central, unifying aspects of Greenhills — its high school and sports teams.

Today, the town’s central shopping strip features a black-operated barbershop and beauty salon, and five-year estimates from the American Community Survey suggest about 13 percent of Greenhills’ 3,600 residents are black. That’s about half the proportion found in Hamilton County overall, but it’s way up from just 3 percent a decade ago.

If the social forces defining Greenhills have been dynamic and shifting in the past few decades, the sturdy, simple structures workmen built 80 years ago seem more permanent. But they, too, are subject to the march of time.

Kugele can’t forget the day she saw the apartment on Cromwell Road where her mother lived out her final years demolished. They joined other buildings in the C-Block on Chalmers Lane, which were also torn down.

“I drove down there and I saw the staircases,” she says of the apartments on Chalmers. “The stairs to the second floor just out there in the rubble. I thought, ‘Someone take those.’ The wood still appeared solid. They’re from 1938, and they were still standing. I couldn’t believe they tore those down.”

In the early 2000s, the village government took control of the properties on Chalmers and Cromwell, which officials say had badly deteriorated. But repairing them would have cost an estimated $4 million, money the village has said it doesn’t have. So, after trying in vain to sell the structures, the village razed them in 2017.

It wasn’t the first swath of demolitions. A decade ago, Greenhills officials moved forward with a plan that required the demolition of 52 apartments from the original village, saying they were beyond repair. Those buildings had been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1989, but that alone didn’t save them.

Those demolitions triggered efforts to get Greenhills listed as a National Historic Landmark, which affords extra protections to historic structures. Preservationists won that status for the original core of Greenhills in 2017 — months before the buildings on Chalmers and Cromwell came down.

“Unfortunately, at this time, there isn’t really a plan to preserve these buildings,” says Richardson of the Greenhills Historical Society. “We thought, since we are a National Historic Landmark now, we thought maybe this would stop. Well, unfortunately, six months later, they tore down 26 more units (on Chalmers and Cromwell).”

The federal government seems to agree to an extent. A month prior to the demolitions, the village received a stern letter from officials with the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees National Historic Landmark designation and historic preservation at the federal level.

"It is discouraging that many of the same concerns and issues that had occurred eight years ago still appear to be present today, after designation as an NHL," the letter reads. "The concerns we expressed over the earlier tear-downs and new construction were acknowledged as the NHL process was undertaken, but ultimately it was felt that the national significance of the village, the entirety of the remaining resources, and the intactness of the original village plan and associated greenbelt outweighed the loss of historic fabric."

"Bear in mind that the shared heritage and stewardship of the village should extend throughout the community, and decisions made today will impact current and future generations," the letter continues.

Richardson acknowledges that the situation is complex. Like a lot of smaller municipalities, Greenhills — which brings in only about $2 million in revenue a year — is smarting from state cuts to local government funding. It’s also dealing with a declining population and the simple fact that much of its housing stock is 80 years old.

“I sympathize with the village,” Richardson says. “Unfortunately, we have a lot of empty land now sitting and I don’t think they’ve really found a developer to build the new housing.”

But Richardson and other preservation-minded Greenhills fans have applauded a move by the village to hire John Senhauser, a former chair of the Cincinnati Historic Conservation Board and a professional architect, to design new housing that will fit in with the neighborhood’s aesthetics.

Challenges linger, however. Easy access to highways make the kind of insulated, self-contained communities Greenhills was designed to be harder to sustain. Suburban-minded homebuyers generally want bigger properties than those on offer in Greenhills’ historic core. And those looking for smaller digs have shown a continued preference for living in larger, denser neighborhoods in the urban cores of cities like Cincinnati — the very places Greenhills was designed to provide refuge from, and where bars, restaurants and employment are easy to get to today. As a result, Greenhills has found itself in the middle of two trends sprinting away from its core design.

Richardson argues it doesn’t have to be that way, though. Many of the amenities young people are looking for in cities — walkability, close-knit communities, historic features — are here in Greenhills, with the added benefit of a bevy of green space and low prices.

“I know right now we’re struggling, but I really hope we attract some young people,” he says. “You’ve seen the revitalization of places like (Cincinnati neighborhood) Northside. What if Greenhills was next? We’re such a great walking town.”

The other greenbelt towns offer differing illustrations for the fate of the model briefly taken up by the federal government. Greenbelt, Maryland, for example, still contains a co-op grocery, pharmacy and restaurant, the New Deal Café, and nearly all of its original structures remain intact.

It has also partially overcome its segregated past. Currently, Greenbelt is home to about 23,000 people — 41 percent of them African-American, though most of the town’s black residents live outside its historic core.

While some preservationists see Greenhills’ legacy in structural assets that need to be saved, others have a broader, more philosophical take on the importance of the New Deal-era village.

As housing gets less affordable and as the nation continues to struggle with income inequality, racial strife, deeply pressing environmental issues and the fragmentation of civic bonds that knit together communities, some wonder if there are modern lessons to be taken from planners’ experiments in Greenhills.

Perhaps more now than at any time in the past eight decades, the questions asked in the 1939 film The City are ringing again.

“It wasn’t the utopia I thought it was growing up,” Seery says, “but yes, it worked. And so I reflect all the time, what is the Greenhills of today? What would it look like? Would it be accepted at all? We’ve had public housing, but not community building. There’s such a need for that, but I don’t know that we’re in the mentality to accept the kind of diverse community building that would embrace everyone.”