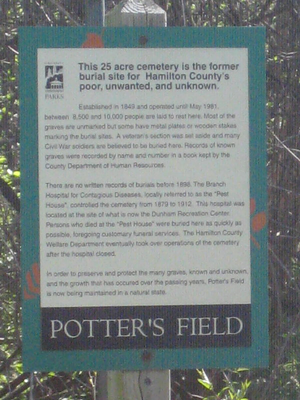

Cincinnatians call an overgrown and neglected piece of rolling land in Price Hill, “Potter’s Field.” A plaque and historic marker say that the site was used between 1849 and 1981 and that it is the resting place of between 8,500 and 10,000 souls.

Both statements are wrong.

More importantly, they perpetuate a dark secret about the boundaries of the cemetery. The true story of Potter’s Field is long and shameful, stretching from its current state of neglect back to the mid-1800s.

The name “Potter’s Field” is Biblical. In remorse, Judas gave back the money that he earned from betraying Jesus. The priests and elders used it to purchase land from a potter. Exhausted of its clay and now useless for farming, they dedicated the land “to bury strangers in.” By the 19th century, Potter’s Field had become a universal name for the unconsecrated cemeteries where communities bury their indigent dead, transients and criminals.

The location that we call Potter’s Field today is roughly 26 acres on the northwest side of Guerley Road. The city acquired the land in 1852, not 1849. An accurate number of how many people are interred there is unknown for a variety of macabre reasons.

By the 1880s, Cincinnati had seven medical schools that required hundreds of dissection subjects each semester. Legal sources for acquiring so many bodies were insufficient, so the schools relied on corpses stolen from local cemeteries, and Potter’s Field was a popular source of supply. As a result, official tallies portrayed an inaccurate body count; and many inaccuracies were rendered moot when a fire destroyed all burial records prior to 1890. However, the sources that have survived indicate that over 20,000 people were laid to rest in Potter’s Field.

The site was used until it became so crowded that graves were dug to a depth reportedly as shallow as 18 inches. The newly deceased were stacked on a previous generation, and the oldest part of the site contains three layers of bodies.

By the early 1900s, overuse of the land forced the city to expand. According to a May 1911 article, the city closed “the old burial ground” and began using a new 40-acre site “on the west side of Gurley [sic]” “across the road” from the original site.

The most important inaccuracy in Potter’s Field history is its boundaries. In truth, what we call Potter’s Field today is only a portion of the cemetery.

During the Great Depression, the down-on-their-luck were dumped into mass graves without coffins because no one identified them.

Like countless families, municipalities also struggled with empty bank accounts. Probably for fiscal reasons, City Council transferred roughly half of the original Potter’s Field to the Board of Park Commissioners in 1934. Lick Run Park was greatly expanded, and the name was eventually changed to Rapid Run Park. Park renovations in the 1940s, including a decorative pond, were constructed without regard to human remains in shallow graves, and workers reported digging through human bones. Expansions of Guerley Road have also been conducted without any apparent regard for the people laid to rest on either side of it.

Itinerate gamblers, prostitutes, unknown vagrants, petty criminals and morphine overdoses were laid to rest in Potter’s Field; but malfeasance in life was not necessary to receive the disrespectful fate of Potter’s Field. The city bought the land that is now the Dunham Recreation Area in 1878 to construct Branch Hospital, a large, modern complex that included a contagious disease facility. It enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with Potter’s. During epidemics, it was common for over a dozen indigent or unidentified dead to be buried in a week. People who lost their lives to cholera, smallpox, tuberculosis or the Spanish Influenza pandemic were buried quickly. Often, family members did not learn of a loved one’s passing until after they had been unceremoniously dumped in an unmarked grave. (This scene has been repeating itself in other cities, like New York and Manaus, Brazil, due to COVID-19.)

At least six veterans of the Civil War, one Spanish War vet, an unclear number of WWI soldiers and other members of the armed services are buried without grave markers. During an 1881 heatwave, over 100 people were hastily sent to Potter’s simply because they could not be quickly identified.

Similarly, unknown drowning victims were sent to Potter’s, including people who drowned in the Johnstown Flood of 1889, their bodies propelled by the rushing water to the Ohio River, and washing up on Cincinnati shores after floating from Pennsylvania.

Decent people have been appalled by the conditions at Potter’s Field for generations:

- An 1864 letter to the editor lamented “the squalid misery and filth attending the death and burial of the poor,” describing the mistreatment of corpses, apathetic misplacement of bodies and 18-inch deep graves.

- Throughout the late 19th century, families were often forced to look through medical school pickling vats for the bodies of loved ones that disappeared after being delivered for burial.

- In 1903, the cruel treatment of a mother whose child died of diphtheria shamed City Hall into exploring the “gross carelessness in the burial of the unfortunate paupers,” but the scandal soon faded.

- In 1910, a contingent of miners were outraged by the treatment of fellow workmen who died during hard times. They “found the place in a deplorable state of neglect…Debris of all kinds was scattered about over the lot, and human bones and skulls, bleached by exposure to the weather, glistened in the rays of the sun from beneath the piles of brush and overgrowth.” The sexton’s cows grazed on the cemetery grounds, prompting a destitute mother to erect a four-foot fence around her infant’s grave to keep the cattle off.

- Administrators of the General Hospital and a group of clergy were so troubled by the conditions that they called for its closure in 1917. A decade later, it was still operating and there were renewed concern over high weeds and gross neglect.

Hamilton County Commissioner Edwin J. Tepe is the only public official of merit in this dishonorable history. He insisted that graves be marked with permanent metal markers bearing names, if known.

Today, the only meaningful headstones in the cemetery date to Tepe’s term as a commissioner, between 1960 and 1964. After he left office, family and friends of loved ones were forced to return to the practice of planting wooden crosses or cardboard markers.

By 1969, the Post-Times Star wrote that, “Many dogs, cats and parakeets are given a better burial in Hamilton County than some people get.” Infants were buried in the same coffins as unrelated adults to save money. An ordinary push-mower was the only piece of equipment that the caretaker was allocated to maintain over 26 acres. Chairman of the Ohio Civil Rights Commission remarked that “the war criminals executed after the Nuremberg trials were given better burial,” but nothing changed.

The living had a more casual relationship with death in the 1800s, but the callousness of Potter’s Field grew harder to justify as the 20th century progressed. Finally, modern sensibilities collided with 19th-century barbarity in 1980.

Through a series of errors, Kathryn Owens did not learn that her father, Charles Hensley, had died on January 16, 1980, until after he had been buried as an indigent in Potter’s Field. She contacted a funeral home, got a court order, and had his body exhumed for a proper family funeral. Upon exhumation, Owens and her two sisters were aghast at what they found. Hensley’s naked body had been wrapped in a bloody sheet and deposited rudely in a thin pine box, along with his clothes and glasses stuffed into a plastic bag. His wallet, which contained contact information for his daughters, had gone missing. Owens and her sisters filed a complaint against Robert R. Wissel, the Hamilton County Welfare Department official in charge of supervising Potter’s Field, and the Prosecutor’s Office charged Wissel with criminal abuse of a corpse.

Negotiations between the prosecutor and county officials followed. Mr. Hensley’s daughters sought improvements at Potter’s Field. In exchange for dropping charges against Wissel, they wanted the hog removed that was grazing on the graves, adoption of “comprehensive regulations” for upkeep of the cemetery, and the installation of grave markers. The case was eventually dropped, but any promises made by Hamilton County were immediately forgotten.

Rather than improve conditions, Hamilton County Commissioners abandoned the site, turning over full control of Potter’s Field to its true owner, the City of Cincinnati. The city was forced to render it hog free, clean it, clear it and mow it. Once. After this single act of responsibility, a Parks Department official explained that his department lacked the resources to maintain the cemetery. Therefore, Parks decided to “let it return to the natural state, for the dignity of all who reside there.”

What followed was decidedly undignified. A new era of public calls to improve the cemetery began:

- In April 1981, the caretaker was fired and evicted from his home on the grounds without warning. Seven months later, a letter to the editor complained that Potter’s Field “looked like a garbage dump,” littered with “beer bottles, old worn-out tires, etc.”

- By 1982, it was covered with knee-high weeds again. When informed of the problem, City Councilman Charlie Luken said that the city should clean the cemetery up and continue to maintain it. He noted that, “If a private land owner had done this, there would be so many orders slapped on them, they wouldn’t know which way to turn.” Council member Bobbie Sterne also advocated for a permanent, dignified solution. In this brief moment of public scrutiny, Potter’s Field was mowed for the second and last time. Four decades of uninterrupted neglect followed.

- In 1987, U.S. Senator John Glenn demanded accountability for the conditions of Potter’s Field from Cincinnati City Hall but, based on an opinion by the City Solicitor’s Office, no action was taken.

- In 1999, a series of articles by The Cincinnati Post again shamed city officials into partially clearing part of the property, but there was no lasting change in policy.

Today, it is impossible to walk across Potter’s Field without wielding a machete. Most of it is covered in thick tangles of honeysuckle, thorn bushes and dense undergrowth. Groundcover is sometimes punctuated by debris. In the most traversable sections, you can stumble across the grave markers of people buried in the early 1960s. Some names are incomplete. Some placards simply read, “Unknown” or “Unknown Infant.”

Conditions at the recognized part of Potter’s is only part of the problem. Historic descriptions of additions to the cemetery do not comport with the modern, recognized boundaries, and complex legal descriptions in 1800s deeds add confusion. A comprehensive survey would be necessary to understand the true boundaries of Potter’s Field.

Kevin Pape, whose firm Gray & Pape oversaw the archeological removal of human remains from Washington Park during its renovation, says that he commonly finds historic cemeteries in Ohio in a state of shoddy neglect, and that true boundaries are frequently inaccurate. It appears possible that part of an apartment complex and a subdivision may be sitting on top of a graveyard.

Many states, including Kentucky and Indiana, have laws that protect skeletal remains in abandoned graveyards and Native American burial grounds, but Ohio does not. The state ranks at the “bottom of the list” for protecting these sites, according to Alan Tonetti of the Ohio Archaeological Council. There are an estimated 17,000 inactive or abandoned burial grounds in Ohio, and the owners of the land can treat these sites with as much or as little respect as they choose.

Tonetti has been working to change this for over 30 years, spearheading legislation that has garnered a sponsor in the Ohio Statehouse roughly once a decade since 1990. Each time, opponents have strangled the proposed bills in their cribs. Following years of discussion and compromise to appease organizations including the Ohio Farm Bureau, Indigenous tribes and the Ohio Real Estate Commission, the most recent draft of a burial bill has come farther than any of its predecessors. It was on the cusp of being introduced to the Ohio Legislature when COVID-19 hit. Tonetti remains cautiously optimistic about the prospects of the current version of the bill, but its fate is uncertain.

In Cincinnati, Potter’s Field was not a priority even before COVID-19 helped jack the city’s deficit up to around $81 million. David Gamstetter, who retired as Cincinnati Parks’ Land Management and Urban Forestry Manager in 2019, has been one of several Parks employees who have been troubled by the conditions at Potter’s Field for years. He envisions a cleared, respectful, forested space.

However, at present, Gamstetter notes that Parks does not have a budget or a plan for maintaining Potter’s Field, and “almost everything on the land is an invasive species.”

In the absence of any state law governing the treatment of human remains, how the City of Cincinnati treats the dead in Potter’s Field, both the recognized and unrecognized portions, is purely a question of morality and dwindling resources. If there is a solution that will finally bring the inhabitants of Potter’s Field the basic dignity that should come with being human, it is safe to assume that the solution will require leadership from outside of City Hall and a source of private funding.

Maybe the COVID-19 pandemic and the related adversities of 2020 will awaken a new sense of humanity for those who rest in Potter’s Field, inspiring Cincinnatians to decide that no one’s memory should be denigrated simply because they leave this world without enough money to buy a plot of permanent real estate. The odds are stacked against it, but maybe this city will finally put an end to almost 170 years of disgraceful neglect.

Michael D. Morgan is the president of Queen City History and Education; a curator of the Cincinnati Brewing Heritage Trail; author of Cincinnati Beer and Over-the-Rhine: When Beer Was King; attorney; and adjunct professor at the University of Cincinnati.