After more than a year of back and forth about short-term rentals like those found on Airbnb and other sites, Cincinnati City Council yesterday finally passed regulations on the industry.

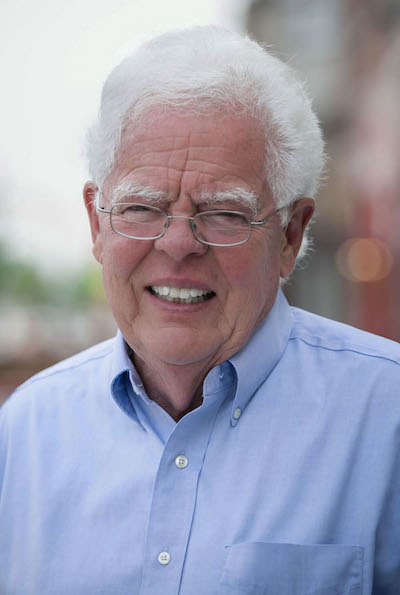

Council member David Mann has been spearheading efforts to regulate short-term rentals. His latest ordinance, which passed unanimously through council's Budget and Finance Committee earlier this month, will starting in July impose a 7-percent excise tax on short-term rental operators, require them to register with the city and self-certify that their properties are in compliance with city code. Proceeds from the tax would go into the city's affordable housing trust fund.

Council approved Mann's ordinance 5-3, with council Democrats approving and Republicans Amy Murray and Jeff Pastor and independent Christopher Smitherman voting against it.

The new version tweaks language found in Mann's last proposal to clarify that the city won't actively seek out Airbnb properties for code compliance inspections and will only respond to complaints. The new language also clarifies rules around nuisance complaints such as public intoxication and gives owners 15 days instead of seven days to respond to code compliance issues.

There are roughly 880 short-term rental units in Cincinnati, most in Over-the-Rhine, Downtown, Walnut Hills, Northside and other popular neighborhoods. That's up from about 830 last November and 640 the site showed this time last year. About 70 percent of those are rentals encompassing an entire house, condo or apartment — up from 60 percent this time last year. The city has seen a 41-percent annual growth rate in those rentals in recent years.

Critics of the industry say it causes noise and other nuisances from guests, incentivizes landlords to pull traditional apartments off the long-term rental market and exacerbates housing shortages, especially in large cities where investment groups operate large numbers of short-term rentals. Cincinnati has a roughly 30,000-unit gap when it comes to housing affordable to its lowest-income residents, though short-term rental supporters claim the industry hasn't contributed to that gap.

Mann's ordinance will prohibit any property owner receiving public subsidies to provide affordable housing from offering that property for rent on sites like Airbnb.

“We don’t want you to have the opportunity to operate Airbnb if you’re receiving support to operate subsidized housing,” Mann said in committee earlier this month. “We don’t want you to take that unit and put it on Airbnb.”

Locally, some residents in neighborhoods like OTR also say the growing number of short-term rentals is changing the character of those neighborhoods. Airbnb supporters in Cincinnati, however, say that isn't the case and that the units actually boost neighborhoods by bringing in tourism spending.

Last year, Mann introduced a more wide-reaching series of ordinances that sought at first to cap the number of days in a year an owner could operate a short-term rental at 90. Mann then proposed a different idea: capping the number of short-term rentals an owner could operate instead of the duration. Those efforts, like the most recent proposals, ran up against stiff opposition from short-term rental supporters. Mann's last proposal also hit skepticism from some of his fellow council members.

A number of local Airbnb owners said they don't mind the tax — which is comparable to what hotels pay — but claimed the code compliance stipulations in the ordinance would be "onerous."

Their main issue: That the ordinance would treat short-term rentals with more than four units as commercial instead of residential buildings, which would make them subject to commercial building code compliance. That was a sticking point before Mann's revisions clarified that the city won't actively seek out short term rentals for compliance inspections.

Some Airbnb owners are still opposed to the ordinance. A few argued in council committee earlier this month that the ordinance's July start date is too soon and that questions about the tax remain unanswered.

Airbnb will collect the tax and remit it to the city.

The company applauded the legislation in a statement today, calling it "pro home-sharing."

"This is a great achievement for our Cincinnati hosts, who fought diligently towards a clear, fair regulatory environment that protects and empowers the home sharing community," Airbnb's statement said. "We commend Councilmember Mann, who allowed local hosts a seat at the table throughout this inclusive and transparent process."

In committee earlier this month, other operators continued to insist that the regulations were unfair.

“There haven’t been any safety issues," a local Airbnb operator told the council committee. "There is no other business platform that monitors a business more than Airbnb. I feel like you’re discriminating against short-term rentals. Many of the things in the ordinance don’t apply to long-term rentals.”

Supporters of the regulations, meanwhile, say they're a good start, but don't go far enough.

"A lot of work has gone into this. It’s very important that city council move on and adopt this. This is a good first step," Legal Aid of Greater Cincinnati's John Schrider said, noting that Columbus, Ohio has short-term rental regulations that are more rigorous and include stricter code-compliance measures and background checks for operators. "We know that short-term rentals are having an impact on our neighborhoods, and we need to study that. But we appreciate the support this ordinance will provide on the affordable housing trust.”