The cleanup crews came in at 7:30 a.m. July 25 to clear out the camp under downtown Cincinnati's Fort Washington Way and disperse any remaining campers there once and for all.

By the time the crews in masks and disposable gloves came with trucks to begin throwing away tents and other belongings and pressure wash the concrete, those who had stayed there were gone. Six left with housing certificates, a couple have gone into job programs, a few others into detox facilities. A dozen or so followed the camp's "mayor," Leon "Bison" Evans — to a new camp at an undisclosed location nearby. That camp, Acting City Manager Patrick Duhaney has said, does not have the city's blessing.

Jessica Barnett was one of the last ones to leave. With the help of a friend, she stashed her tent and personal belongings in a safe location the night before. Then, with just a pillow, a chair and a blanket, she went to sleep one last time under the concrete slab that hums with traffic day and night where she had been staying since April.

"I didn't have anywhere to go," she says.

When she woke up before city crews began arriving, she was at a loss. She walked out from under the cool, shaded overpass up onto Third Street, where she sat on a concrete bench for a while. Below, city crews were preparing to put up fencing to keep camp residents from returning.

Eventually, a man named Desmond approached her. He and several others had weeks ago pitched tents alongside the barrier overlooking Fort Washington Way on Third Street. Would she like to join them? Yes, she would.

Those staying in the spot say they do not want to move again. But they feel the city crews, with their legally-mandated 72 hour notice forms, are likely to come for this camp next.

The Fort Washington Way camp was actually slated for removal a week prior, but advocates and Cincinnati City Council members pushed for a six-day delay to help those staying there find places to go.

Following complaints from the Downtown Residents Association and various business groups, Acting City Manager Duhaney two weeks ago issued a memo calling for the camp's removal, citing public health and safety concerns. Mayor John Cranley has echoed those concerns, saying that police believe drug use and human trafficking have occurred at the camp.

Others, however, dispute claims that the camps are havens for crime and drug use.

"I've been there at all hours of the day and night and I have never observed any dangerous, unhealthy or illegal activity," Jeff McDowell, a communications manager at Procter & Gamble and board member for nonprofit Maslow's Army, told Cincinnati City Council recently. "I'm not denying that we need to address the issues that downtown residents have expressed. They're real. But I'm here to tell you that (camp residents) are part of the solution."

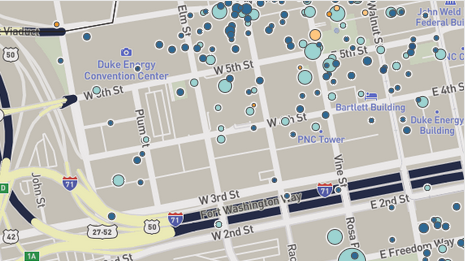

Recent media reports detail the search for a drug dealer operating near the camp. But if there have been other serious crimes in its vicinity, they aren't reflected in the city's crime stats. Though the Central Business District has seen 568 reported crimes since the beginning of February, only a few minor incidents have been reported in the blocks around the camp, according to city data initiative CincyStats. A map of downtown crime complaints shows nearly all since February have taken place in other parts of the Central Business District.

At a noon news conference the day the Fort Washington Way camp was cleared, backed by the Greater Cincinnati Homeless Coalition and Maslow's Army amid a throng of Reds fans streaming into nearby Great American Ball Park, those living on Third Street made their stance clear: They feel they're being swept under the rug, and they've resolved to stay at the camp until the city addresses deeper issues.

Dale Edmonds, one of the residents at the camp, held up a piece of paper listing systemic reasons why people become homeless, from health crises to low wages to lack of mental health care or addiction treatment. Edmonds has been homeless for more than three years.

"If I've got a mental issue, or a social issue, or a disease, help me with that," he said. "Don't kick me to the curb. That's not fair."

Local nonprofit Strategies to End Homelessness counted 7,168 people experiencing homelessness in Hamilton County in 2016— well more than the roughly 1,000 shelter beds and 2,500 units of permanent supportive housing available. Shelters are temporary solutions anyway, say advocates with organizations like the Greater Cincinnati Homeless Coalition.

They point out that Hamilton County needs thousands more units of affordable housing available to low-income residents. A study from LISC of Greater Cincinnati released last year suggests that gap could be as high as 40,000 units. Solutions to bridge that deficit — an affordable housing trust fund recently established by the city, for example — could take years to bear serious fruit.

Barnett wants simple things, she says. An affordable apartment where her three daughters can visit her. A job she can do that provides enough money so she can get by and take care of her kids.

"I've been living in a home all my life up until the last three years," she says. "I want that back. I want my girls to have a place to come back home to with me."

Finding stasis has been hard for the 36-year-old since she lost housing she was staying in via a Talbert House program a few years back. She's been to jail for drug possession. She's had all of her belongings — including her ID, her birth certificate and her social security card — stolen on the street. The lack of those documents makes it hard to find a job, she says, and she hasn't been able to get new ones.

"I know there's the van, but they have 10 spots for all the homeless people in Cincinnati," she says, referring to a new program called GeneroCITY 513 sponsored by the city and social service organizations that pays those experiencing homelessness $45 a day and lunch to do jobs like picking up trash around the city. "People are literally fighting for these spots. People want to work. They want to do things that are useful. It's not that we don't want to do for ourselves, it's that where we don't know where to start again."