Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine emphasized the fact that a new curfew order seeking to stop the spread of COVID-19 would not be perfect. But advocates for the homeless say the order could complicate things for the unsheltered people without homes across the state.

The order itself, signed by Ohio Department of Health director Stephanie McCloud on Nov. 19, mentions an exemption for individuals experiencing homelessness from the requirement to state at home between the hours of 10 p.m. and 5 a.m.

The order also says homeless Ohioans are “strongly urged to obtain shelter, and governmental and other entities are strongly urged to make such shelter available as soon as possible and to the maximum extent practicable.”

But as the pandemic continues, advocates are saying homeless individuals want to avoid the pandemic, and understand that going to a shelter with an unknown amount of people is a risk.

“People are really doing everything they can to avoid having to go to a shelter right now,” said Marcus Roth, director of communications and development at the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio.

The curfew also gets complicated because it can involve enforcement by police, who may not know that that the homeless are exempt from the order, and those without a residence may not know they have the right to an exemption. At a recent press conference announcing the order, DeWine said violation of the order amounts to a misdemeanor charge.

“Generally speaking, we’re always opposed to the punitive approach to homelessness,” Roth said. “Being homeless is not a crime and treating it as such is only making things worse for the individual and the community in general.”

The state and the federal government could be doing more to help people avoid being out in the streets, especially with a pandemic that is causing job losses that could lead to many more people struggling to pay rent or a mortgage, along with the other costs of living.

Generally, Roth said, those facing potential homelessness will exhaust every other option before they are faced with living on the streets, from paying rent with credit cards, to selling other assets like cars or living with other friends or family members.

In a September housing survey conducted by Apartment List, 36% of renters nationwide said they had drawn money from their personal savings since the start of the pandemic, and one-in-four have built new debt either with credit card spending or loans from relatives or friends.

One in ten people have withdrawn money from a retirement account, which typically involves penalty fees.

So-called stays of evictions haven’t stopped the removal of people from homes entirely. While the CDC recognized that adding more people to an apartment or increasing the number of people in homeless shelters would not help the spread of COVID-19, the health order they released in September to pause evictions requires people to file declaratory documents, which prove the resident has tried to pay rent but can’t. The order allows landlords to challenge the eviction stay in court.

“It’s problematic to say the least,” Roth said.

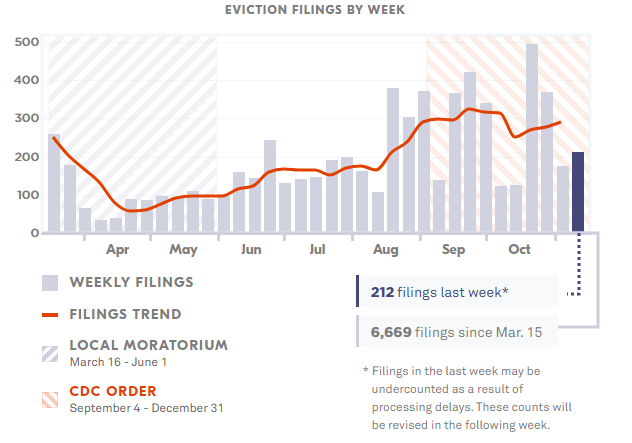

The Eviction Lab at Princeton University, which tracks eviction filings in major cities across the nation, showed Columbus evictions down dramatically in March but they have risen again since then.

The state didn’t implement an eviction moratorium as a whole, but Franklin County courts halted processing of non-emergency eviction filings from March 16 through June 1. As of the first week of November, Columbus reported 212 filings for the week, with a total of 6,669 filings since March 15.

Hamilton County courts also halted eviction proceedings from March to June, though the eviction filings were still accepted. After the June expiration, evictions went back up, peaking the week of Aug 23, with 316 filings that week, according to Eviction Lab data.

The county in which Cincinnati sits has had a total of 4,256 filings since March.

The Cleveland Municipal Housing Court halted non-emergency eviction filings in the same period and saw eviction filings bottom out between March and June. Unsurprisingly, as soon as June 1 rolled around, eviction filings saw their peak, with 344 filings from June 14 to June 21.

The levels have largely dropped below 100 filings since the peak, with a total of 2,273 filed since March 15.

The other issue on the horizon is the expiration of the CDC health order at the end of December, even though the pandemic will still be present throughout the country, according to experts.

The impending deadline makes Roth and other homelessness advocates feel another solution needs to continue and be improved: emergency rental assistance.

As of Oct. 26, the state created a Home Relief Grant program, distributing $50 million from federal coronavirus relief funds to help residents with rent, mortgages or utility bills like water and sewer.

According to the state, the funding will be distributed through the Ohio’s 47 Community Action Agencies. Residents can apply to be compensated for bill back to April 1, but that program also ends on December 30.

“What we’re really concerned about is what happens in January and the months to come, when the CDC (eviction) moratorium expires as well as CARES Act funding for emergency rental assistance,” Roth said. “We could have a serious crisis.”

Roth said Congressional action on a new coronavirus funding bill would be a good first step, but more needs to be done. This also includes more community action, as a shortage of volunteers and an long-standing need for resources hampers shelters and advocacy efforts.

This story was originally published by the Ohio Capital Journal and republished here with permission