Writer-director Jeremy Saulnier (Blue Ruin) knows the simple secret for creating a down-and-dirty little indie thriller: Introduce us to smart, funny characters, but don’t feel the need to burden them with cluttered backstories. Give us violent acts, but don’t linger on the results for very long. Tease us with familiar faces, although you must present them in new and startling ways, as characters worlds away from our general expectations for these performers. And for goodness’ sake, keep it moving.

What you create, if you follow this template, is tension and a sense of urgency of the white-knuckle variety, the kind audiences demand but rarely get from the studios. Which is why we need filmmakers like Saulnier and films like Green Room.

Operating with real passion and desperation, Green Room checks off each box with the precision of a brand-new drill bit burrowing right through the skull. The Ain’t Rights, a plucky Punk band (featuring Anton Yelchin and Alia Shawkat) struggle to make ends meet on the road. They love the music: when it’s firing on all cylinders, the wild nights of gigs in different cities, playing small funky clubs, wearing their influences on their sleeves. They would do anything to maintain this way of life, including siphoning a bit of gas when the tank gets low.

Unfortunately, they are stumbling toward the end of a long and not terribly successful tour run, where the pay barely covers convenience-store snacks and they find that they are getting hustled by small-time promoters. Having cornered a seemingly good-hearted local guy who scrambles and hastily arranges an afternoon set for them, The Ain’t Rights decide to take on one last gig before calling it quits.

Pulling into the isolated club, well off the beaten path in the backwoods of Oregon, every single one of the band members has a moment when their Spidey senses start tingling like crazy. The patrons skulk around in a casual neo-Nazi haze, like castoffs from night of the living skinheads. The Ain’t Rights are Punk Rockers, to be sure, but they don’t have that nihilistic, Punk spirit that’s ready to kick and fight and bleed for anything other than a hot lick.

That is, until after their set. Full of defiance, the band thumbs its nose at the crowd in between serving them an adrenaline kick that gets them fired up. After the show, the band witnesses the aftermath of a murder in the green room. All of a sudden, push comes to shove and The Ain’t Rights are forced to kill or be killed. The movie becomes a Darwinian nightmare, frighteningly all the more real because there are no undead monsters or unstoppable boogeymen wielding knives. There’s no hoping for a superhero to drop in to save the day.

Saulnier steals from the Punk aesthetic when it comes to staging and execution. Refusing to drag us back to the torture-porn vibe that dominated horror at the beginning of the new millennium, the camera never lingers too long on the bloody wounds inflicted. Instead of titillation, we experience the necessary shock of the acts, which either stuns us into a state of inaction or propels us into not-always carefully considered responses. Without realizing it, the audience assumes a role; we become one of the hapless members of the band fighting to stay alive. Do you go valiantly into the thick of battle or do you run, consumed by the instinctive flight mechanism?

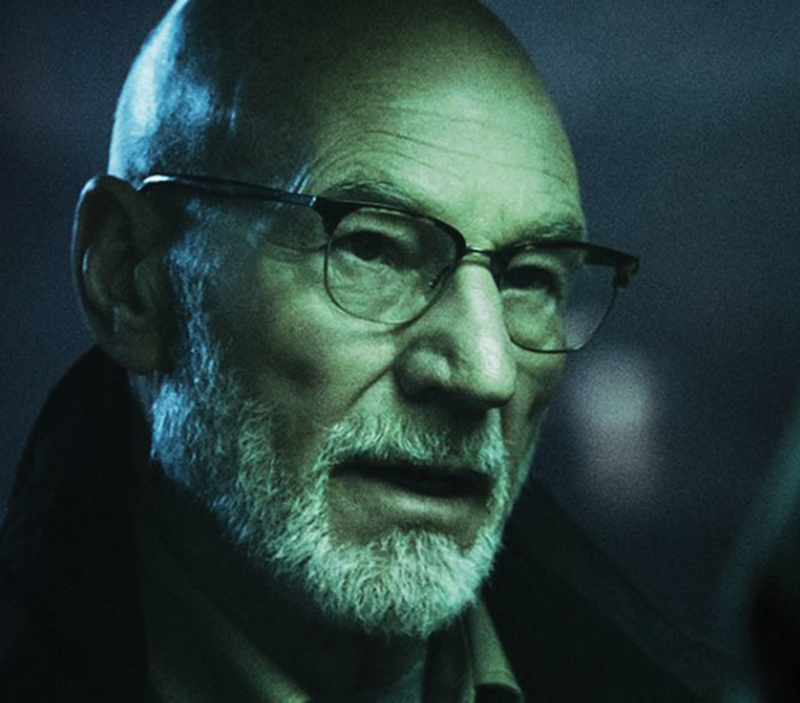

The truly daring and almost-revolutionary aspect of the film is how, even with a performer like Patrick Stewart playing the methodical club owner who arrives on the scene and seeks to clean things up with extreme prejudice, we are never jolted out of the world of the narrative. There are other familiar faces — besides Yelchin and Shawkat, there’s indie ingénue Imogen Poots — but they all commit themselves completely to the dark and dank reality. Not once does Green Room feel like an artificially constructed space, a make-believe movie set dressed up in grunge.

I will admit to being faintly reminded of early George Romero, but the monsters here had human faces, eyes still burning with some semblance of life and a desperation of their own. What happens in Green Room ain’t right, but you’ll find that you are in bloody good hands. (Opens Friday) (R) Grade: B+