News media does its job when readers and listeners know “so what” as well as “what.”

That might take more than one article or broadcast on a given story, but the sum of coverage should allow readers and listeners to decide whether to act and, if the answer is yes, what to do.

It’s not hard to find failures to meet this standard. Consider coverage of Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders. Even if he doesn’t win the Democrats’ presidential nomination, Sanders’ ideas are dragging Hillary Clinton to the left of her comfort zone on Wall Street.

Part of the news media’s problem is Sanders’ embrace of the terms “socialist” or “democratic socialist” to describe his political/economic world view.

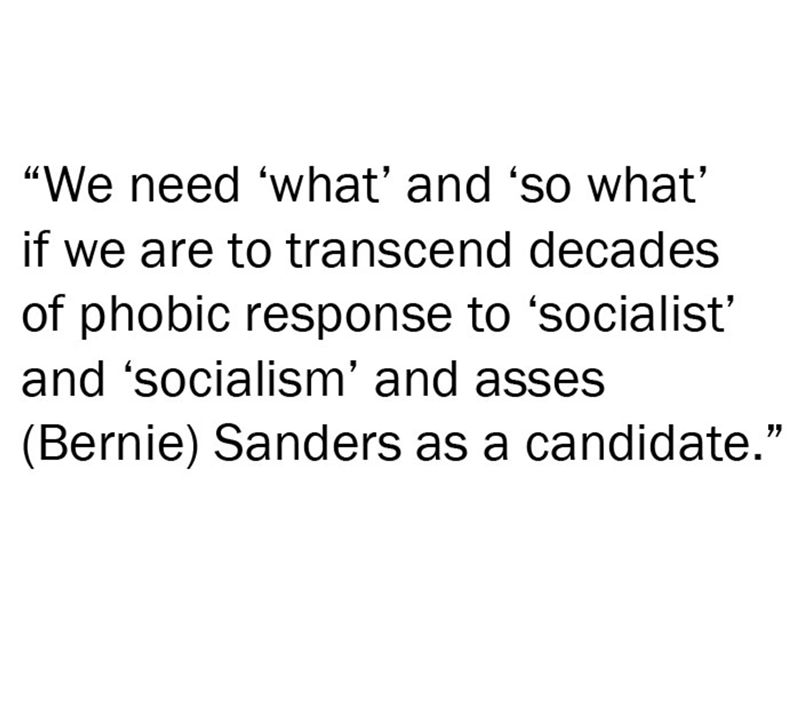

Going to a dictionary won’t suffice. Sanders is too complex and independent for what their definitions encompass. We need “what” and “so what” if we are to transcend decades of phobic response to “socialist” and “socialism” and assess Sanders as a candidate.

This failure of American journalism is no accident. For more than a century, American editorial pages have damned socialism as evil and a step toward communism. Publishers and other businessmen saw socialism as poisonous to their profitable American Way of Life.

Today, only the hopelessly paranoid — communists and anti-communists alike — believe socialism inevitably leads to Marxist-Leninist communism, but “socialist” still evokes strong reactions among voters and journalists who couldn’t tell you what it means beyond “it’s bad” or “it’s unAmerican.”

What we’re missing are explanations of how democratic socialism operates in Europe and Israel and how so many of our lovingly embraced national policies reflect what once were seen as treasonous socialist toxins.

In the absence of thoughtful coverage of Sanders’ ideas and Senate votes, I’d recommend two magazines friendly to modern democratic socialism: The Nation and The Progressive.

Or listen to Sanders.

• Photojournalism came under renewed scrutiny in the past few days. Critics asked whether anyone needed to see the dead Syrian child face-down at the water’s edge after his family’s failed attempt to flee by boat.

I would have taken that picture and I would have argued for its publication; photojournalists capture what happened in an instant, not what we wished would have happened.

We’ve seen images of drowned migrants before, bobbing in the Mediterranean or being carried ashore in Italy or Greece. Maybe it’s cumulative empathy, but response to the photo of the dead Syrian child is different.

Two images were commonly used in print and online. One was a classic news photo: a Turkish policeman carrying the 3-year-old away from the water. More provocative was the photo cropped to show Aylan Kurdi alone in the sand. For many, it is one of those images that comes to symbolize a human plight.

This kind of impact isn’t new. Recall the naked, badly burned girl fleeing combat in Vietnam or the starving Sudanese child being watched by a vulture.

Many editors explained why they used the picture of Aylan in the sand. Some others buried it in larger report of the tragedy rather than putting it on front or home pages.

Editors generally said it was to put an individual human face on a larger human tragedy. The other photo — the policeman carrying Aylan — didn’t seem to require any explanation other than the usual information of who, what, when, where and why.

• What appears to be an insider argument addressed ethical questions as broad as photojournalism.

It began when a French photojournalism exhibit rejected the work of a photographer who had his international prize revoked because he misidentified an image and added a remote light to another image.

The French show, which the New York Times called the world’s leading photojournalism festival, Visa Pour l’Image, also refused to show other winners of the same contest. Here’s part of what the Times reported from Perpignan:

“The prestigious World Press Photo contest caused an uproar in March and damaged its standing when it bestowed, then revoked, a top prize to an Italian photographer who had misrepresented the location of an image.

“Amid an intense debate about the line between photojournalism and art photography, many photojournalists were outraged that images in which the photographer, Giovanni Troilo, had intervened — by using a remote-control flash, for example — had been categorized as reportage.

“Soon after the controversy began … Visa Pour l’Image said that it would not display the World Press Photo winners’ work at its annual gathering here, not only because of the Troilo controversy, but also to protest the contest’s editorial choices.”

Meanwhile, the Times said, “Lars Boering, the managing director of the World Press Photo Foundation … announced that officials were writing a code of ethics and revising their rules to make clear that staged images would not be permitted.”

• Over the years, the Enquirer has done good work on major breaking stories. Reporters, photographers and editors “swarm” the subject. In the past few days, under the new publisher and newer editor, they did it again with good results: coverage of the firing of Cincinnati Police Chief Jeffrey Blackwell and the damning report on the killing of an unarmed driver by a UC cop.

Short of swarming a story, the next-best approach is giving the Enquirer’s James Pilcher time to dig and write. On Sept. 13, Pilcher took his scalpel to authorities taking people’s cash — civil forfeiture — without arresting or prosecuting them. Once meant to deter cash-based drug trafficking, civil forfeiture became a cash box for local authorities who keep most of their loot.

• And here I go spitting into the wind again, but I don’t like “sponsored content,” even when it’s clearly signposted. It looks too much like real news, and that’s the point: It imitates news to draw on the validity of the real thing.

A recent Sunday Enquirer topped a local page with sponsored content, a byline and a headline meant to resemble news: “Research links hearing loss to higher risk of falling.”

Given the demographics of newspaper readers — we’re old and afraid of dying after breaking a hip — this was a well-done ad. Contents might be accurate, but that’s all it was — an ad, and it should have been designed and labeled as such.

• Variety’s premature obit for Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam gave him a chance to show he hasn’t lost a beat. This was his Facebook retort:

“I APOLOGIZE FOR BEING DEAD especially to those who have already bought tickets to the upcoming talks, but, Variety has announced my demise. Don’t believe their retraction and apology!”

The photo showed the 74-year-old comic lying “dead” in bed with a friend holding a sign, “HE WAS ONLY 30! Bad reviews from Variety AGED HIM!”

CONTACT BEN L. KAUFMAN: [email protected]