Every time I heard my mom start her daily call with my Aunt Gertrude, I cringed. Within seconds, my mom’s voice — usually crisp, clear and accent-free — slowed to the kind of drawl people heard (and mocked) on Beverly Hillbillies.

On days when I was home to hear the call, I cranked up the volume on The Price is Right so I wouldn’t have to listen to her talk — and talk and talk — in that voice. I wouldn’t have to hear her drawl on about tragedies and triumphs of cousins I’d never met, of the grandparents I’d never known and of food I most certainly did not want to eat. And it was an accent that I associated more and more with what I saw in the media.

In the early 1970s, reruns of Green Acres, and Petticoat Junction and first runs of Hee Haw regularly brought hillbilly stereotypes into our living room. At best naïve, and at worst mentally inferior to their big-city peers, the media-defined hillbillies were cheap-laugh sacrificial lambs with bad teeth and an inexplicable predilection for outhouses. Surely, I thought, my family had nothing in common with those people, people who laughed too loud and swore as much by nonsensical old wives’ tales as they did by their bibles.

We were different, or so I convinced myself, even though most of my high-school peers had family “down home.” A place I imagined as some unnamed, undeveloped town in Kentucky from which their parents had escaped. But on weekends, after their dads clocked out of work at Norwood’s General Motors’ plant (now transformed into a maze of strip malls and medical offices), my classmates seemed excited to leave town and visit “mamaw” and “papaw,” terms of endearment as foreign to me as the thought of getting a Trans Am for my 16th birthday.

My family didn’t take trips “down home.” My mother, the youngest of 14, graduated high school at 16 and not long after moved, by herself, from the southeastern mountains of Kentucky to Norwood. She met my dad, an only child, during his last year at Norwood High School. I was their sixth and final child and by the time I was born, my mom’s parents were long dead and her surviving siblings and most of her cousins had also migrated north, leaving Letcher County for better jobs in Ohio and Illinois.

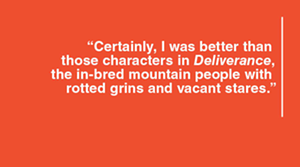

Today, when I think back to my cringing when I heard the accent and my constant questioning of her: “Why do you talk so funny when you talk with your sisters?” I recognize I was a snob. And perhaps worse yet, I believed the stereotypes of people from Appalachia I saw in the media more than I believed in my mother. Though I repeated my mom’s stubborn mantra, “No one is better than you, and you aren’t better than anyone else,” I focused on the first part of the phrase more as it helped me fight near-crippling shyness. Certainly, I was better than those characters in Deliverance, the in-bred mountain people with rotted grins and vacant stares. Appalachians were in turns ignorant and scary, and I wanted nothing to do with them.

But I now understand that I did have much in common with them, starting with my mom’s daily phone calls with Aunt Gertrude — and Aunt Georgia, and Aunt Mildred. Those conversations warmed my mom like a soft quilt made from generations of rich, familiar fabrics.

Her ease with people went beyond family. She could elicit the best and most intimate stories from anyone, from elderly neighbors to cashiers. And she had great stories of her own, though I had to beg her to share them. Stories of helping raise her sister Mildred’s daughter, of working in a retrofitted factory in California during World War II after my dad shipped overseas, of the father she idolized and the mother she lost too soon.

But I spent most of my youth embarrassed by her easy way with the world, her insistence on talking with clerks and neighbors, hanging on to their stories and remembering details that continually surprised them weeks and months later. I would try to pull her away, urging her to hurry, and bristle when she stubbornly ignored me and turned back to hear their stories.

It wasn’t until years later that I came to see the value of being “stubborn” in my own life as a journalist and teacher. And how much I learned simply by listening to my mom have conversations with her family and the hundreds of people she met in her life. It wasn’t until years later that I came to understand that the second half of my mother’s mantra was just as powerful as the first. And it wasn’t until years later that I felt a sense of comfort and confidence in calling myself an Urban Appalachian.

The shift in accepting where my family came from began when I volunteered at a “last chance” high school down by the river. I worked with a smart 16-year-old who was living on his own after a short stint in juvenile detention. He was a thoughtful young man with a big heart and a love of poetry. We worked on algebra and calculus, and I prayed every week when I came back, he would still be in class, ready for our session.

Then one day he wasn’t.

I learned he had been arrested for shoplifting and was headed to prison. Not long after, I enrolled in graduate school to become a teacher full-time, determined to support and give voice to students like him.

After graduate school, I volunteered at a GED program in East Price Hill. My students were working multiple jobs, taking care of their children and spending hours on study prep guides and practice tests. Nearly all of them talked just like my mom during those daily Aunt Gertrude calls.

My revelations about my heritage were more like slow-burning candles than light bulbs, illuminated through narratives where switching a word here or there made all the difference. Replace “stubborn” with “determined,” “strong” or “resilient.” Replace “uneducated” with “hard-working.” Replace “poor” with “family-focused.” Replace “hillbilly” with “rooted.”

Slowly, I replaced the media stereotypes I believed defined me with the actual people I knew in Norwood, East Price Hill and beyond.

Certainly, not all Appalachians — rural, urban or otherwise — embody only the culture’s strengths. Nor, importantly, are they all white, poor and uneducated. I learned to recognize that my stubbornness is born of my Appalachian heritage and see it as the result of generations of survival tactics as much as pride. I also learned to use that stubbornness to root out stories other journalists failed to see and find answers to questions others never thought to ask.

Today I revere the stories of the people — my people — who are buried on mountaintops, even in death protecting the land from the coal companies that would destroy them. And today, I’m proud to play a part in rewriting the media narratives that made hillbillies ripe for elegies instead of celebration.

Writer, editor, educator and communications consultant Elissa Yancey is participating in the Appalachian Studies Association Conference, sponsored by the Urban Appalachian Community Coalition, an organization with roots in the East Price Hill GED Center she describes. The conference will be held in locations throughout Greater Cincinnati from April 5-8. Find details and register at uacvoice.org.