Cincinnati is a Midwestern pillar of Catholicism, speckled in stained glass windows that depict saints and gospel tales, and cast murky shadows of Christian lore onto the laity. These images embed themselves into the community’s psyche — perhaps more so on the West Side than anywhere. So, it’s conceivable, in a place like this, that a sheltered Catholic boy could confuse his epileptic seizures with demonic possession and not want anyone to know what he’s suffering.

That happened to local author Steve Kissing while growing up, and he has just published Running from the Devil — a book both narratively and visually graphic — to tell about it. His story, adapted from a 2003 memoir by the same name (which stemmed from an essay published in Cincinnati Magazine in 2000), reveals the panic and anguish of “a boy possessed.” Charles Santino worked as the scripter and Jim Jimenez as the illustrator.

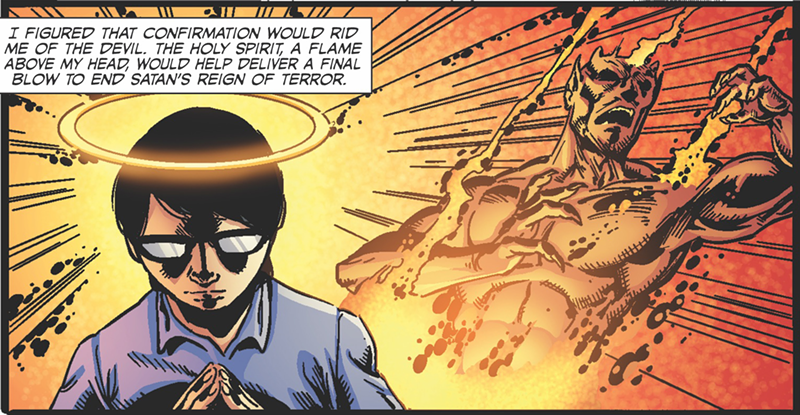

The colors and layout hearken back to ’70s comics. Bold colors pop off the page, and though the art is realistic, it often dips into a dreamscape where the devil meanders above Kissing as he cringes in pain. In another scene, Kissing holds a pillow over his ears and scrunches his face; the devil looms above him, one claw lurching for his body.

Kissing says he grew up in a Catholic bubble. Throughout his childhood, he attended Catholic school and graduated from Price Hill’s Elder High School in 1982. Through all those years, he experienced seizures. But he thought he was possessed by the devil and — a product of his cultural environment — he kept the episodes hidden.

“I think that if, when I had these so-called satanic visits — if blood had been coming out of my nose or ears or if I had been vomiting — I’m pretty sure I would have spoken to my parents or they would have noticed themselves,” he says. “I think the fact that it was easy to hide and hard to explain created the perfect storm for my whole situation.”

At age 11, he first experienced a seizure inside of St. William Church, surrounded by iconography of the faith; he describes the arching dome above the altar, a reaching statue of Jesus and flickering candles obscuring figures of Mary and Joseph. Between the pews, he felt safe.

In the midst of the seizure, the world morphed into odd hallucinations. This sensation could have only been caused by the demons they spoke of in church, he thought. And, as noted in the graphic memoir, The Exorcist had just been released a year prior — a film that was said to be based on a true story. So, couldn’t the same horrors befall him?

Kissing wants his story shared so that young people might relate to it; maybe not so much to experiencing seizures, but the process of navigating one’s identity outside of the bubble they were raised in.

Much of the novel is spent exploring this truth. It’s a coming-of-age tale, but instead of Peter Parker’s radioactive spider bite acting as the jumping point, the concept of demonic possession is what drives this narrative.

Kissing later learned that he was not possessed. During a youth conference, he had a grand mal seizure, which involves a loss of consciousness and violent muscle contractions. After a series of tests, he was diagnosed with a seizure disorder (epilepsy) and told that’s what he had experienced all those years. Though they have now ceased, the root cause of them is still unknown.

Once he entered college, Kissing left the Catholic faith.

“Given how influenced and committed I was to (my faith), it was a hard thing to separate myself from it, and it took more than a decade to do that,” he says. “There’s still a lot about the Catholic church I like and admire, even if at the end of the day I’m no longer a believer and have trouble with all sorts of things.”

He says that the story first emerged from a writerly need to recount his experience — first in the form of a personal essay. Nearly 20 years later, the graphic element was added. His four daughters also grew up in that time frame; he currently lives with his wife and works as a managing partner of Wordsworth Communications.

“That separation (of time) definitely helped,” Kissing says. “It just gives you some perspective. I had also been a parent. That gave me a perspective into my childhood and parenting. I spent a good three months not writing anything other than trying to capture my memories in this three-ring binder about key people, places and events in my life. I would just scribble things as I remembered them.”

Though such subject material can feel emotionally heavy, humor was a consistent pulse throughout. He sees his story less about angst and more as an oddball tale.

“I still find it fascinating. I still have these moments where I have to remind myself that it happened. And I think that it speaks to the power of a child’s imagination, too,” he says, adding that it makes him wonder what worlds his own kids manifested. Because Kissing is reaching back into his memory, and the tale itself feels hazy.

Like the memoir and essay that came before it, Kissing ends Running with a quote by John Milton, from Paradise Lost: “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.”

Kissing says, “That quote, given what I experienced, could say a number of different of things. I kind of created my own heaven and hell inside my mind, but wrapped around me were these broader concepts of heaven and hell — the culture that I grew up with. It also speaks to my point of view now, in terms of how I would define heaven and hell.”

In the end, Kissing faced both real and fictitious demons. The seizures may have guided the narrative, but at its core is a story of place, culture and adolescent fever dreams — the chase to be holy despite oneself and the need to hide our faults.

Find more info on Running from the Devil at runningfromthedevil.com.