New York Times art critic Holland Cotter recently titled his review of an L.A. gallery exhibition featuring all abstract sculpture by women with the pejorative question, “Are All-Women Shows Good or Bad for Art?”

Eye roll. His answer, of course, is implied by the query itself. Why would women want to set themselves apart as “outsiders” when the aim — to Cotter’s mind, at least — is “full integration into the larger art system?”

But perhaps large group shows featuring artists who’ve been left out of the annals of art history go beyond just aspiring to be a part of the system. If you already know that the system is broken, why buy into it?

Likewise, in exhibitions that feature the work of artists of a common race — typically a curatorial decision, but not an uncommon or even consciously made one, given the white male-leaning canon — the onus often lies upon the artwork’s ability to mitigate and/or interrogate that power imbalance.

30 Americans, an exhibition that originated during Art Basel in 2008 from a loose premise of 31 — nope, that’s not a typo — selected black, American artists from the collection of Mera and Don Rubell, recently opened at the Cincinnati Art Museum. It is a show that quite literally overflows with art from internationally renowned artists that speak to the power dynamics of race, class and political identity.

The Rubells’ only stipulation for each subsequent iteration of the show (five to date) is that administrators include every one of the initially selected artists, giving curators access to their own collection of 280 artworks by the prescribed artists and the freedom to include whatever other works by the artists the hosting institutions might also have access to.

For the show at the CAM, co-curators Brian Sholis (CAM curator of photography) and Rehema C. Barber (director and chief curator of Tarble Arts Center at Eastern Illinois University) arranged the exhibition’s layout to include three broad themes: economic issues, particularly the commodification of African-American culture; the characters people play and how they are caricatured; and how individual rights are shaped by politics.

One of the most obvious commonalities among such a disparate grouping is the oversized scale of much of the work, a quality that speaks to the sheer force of these voices, as well as to the visceral quality of the work.

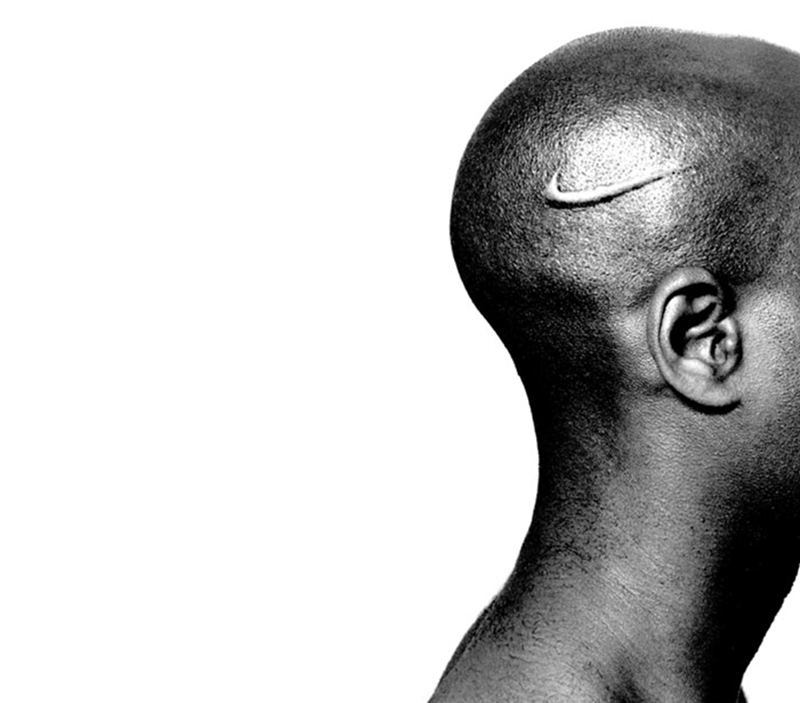

The show features installations, paintings, sculptures, videos and photography from the likes of such art-world luminaries as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Hank Willis Thomas, Kehinde Wiley, Robert Colescott and Nick Cave.

Because much of the artwork in 30 Americans is quite large, the show not only takes up all of the second floor’s changing exhibition space; several other pieces are installed on the first floor as well. In fact, according to museum director Cameron Kitchin, the show is too big for any of the museum’s single-exhibition spaces.

Wiley’s ginormous 11-by-25-foot painting of a scantily draped black male figure, prostrate like a martyred Jesus sans Virgin, “Sleep,” is flanked by portraits from European masters Thomas Gainsborough and Anthony van Dyck; it greets visitors to the museum as they walk through the corridor-like Schmidlapp Wing, setting a powerful tone for the rest of the exhibition.

In the first floor changing exhibition hall, curators thoughtfully juxtaposed Kara Walker’s iconic paper silhouettes tackling issues of black female representation since slavery, “Camptown Ladies,” with Leonardo Drew’s imposing, minimalist 8-and-a-half-by-13-foot wall of white cotton blocks. In doing so, Drew’s “Untitled #25” remains a formal reference to the grid and a reminder that these materials were once used to justify an entire economic system based on racism.

Two separate large-scale sculptural installations by Gary Simmons, “Klan Gate” and “Duck, Duck, Noose,” aim directly at racism as a function of the educational institution, while oversized figurative paintings by Mickalene Thomas and large-format Chromira C-print photographs by Xaviera Simmons subvert depictions of black femininity.

An installation of 38 lithographs on creamy white felt, “Wigs (Portfolio)” by Lorna Simpson from the CAM’s own collection, and Rodney McMillian’s Shroud of Turin-like carpet painting “Untitled” — which is literally the size of a room — are just a few of the pieces that haunt the visitor for days after viewing.

There is so much to see in 30 Americans, it could easily be broken up into several smaller shows. Indeed, there isn’t even enough room in this review to dedicate to the amount of profoundly moving work.

So if large group shows of underrepresented groups aspire to counteract lack of visibility in the art world, perhaps the next step might be not for us to exclude such exhibitions altogether, but to have many more of them.

30 AMERICANS is on display at the Cincinnati Art Museum through Aug. 28. More info: cincinnatiartmuseum.org.