I

write this to the slurred black icky thump of D’Angelo’s “Devil’s Pie” (I know I/was born to die/searching to find/peace of mind),

pausing occasionally in my writing cockpit to look up at the grainy, overdeveloped black and white Polaroid of my parents on the Hamilton porch of my girlhood home.

There is no phantasmagorical narrative.

Their body language tells a sweet story.

Sitting on an aluminum chaise lounge my memory says had orange and yellow flowered cushions, my mother wears a sleeveless white belted dress with a narrow matching necktie. Her straight black hair brushes her collar; her long legs are crossed at the ankles and her large left hand rests intimately and comfortably on my father’s right knee. Her forearm stretches the length of his thigh. Her elbow rests up near his pants pocket. He is wearing a shirt with sleeves rolled twice casually, the way men do before doing a task. Sitting behind her, he leans into her, his right shoulder disappearing and pressing into her back. She looks forward, smiling wryly like a black martyr with a secret; he’s smiling widely and looking at her adoringly.

I stand with my father in the short shadow between the era of this picture and every Father’s Day. Abiding with me are awe and embarrassment; reverence and confusion; profound loss in the absence of my mother and unshakeable aggravation in the presence of my father.

Last time I saw my old man — I’ve always wanted to say that and now he is old — we were in the low-ceilinged basement-cum-family/gathering room of the Forest Park home where he lives out his days with my stepmother.

“You tried to ruin me,” he said to me in a raspy, feeble voice colored surely with misplaced anger and un-Christian grudges. He said this to me at the end of a “family meeting” called by him and for him. After I’d told him his generic, falsely contrite apologies to a young family member for heinous behaviors he was trying to absolve needed more sincerity and specificity, he waited until the meeting had broken completely down under the weight of everyone’s emotional, tear-soaked lamentations before he got me.

I was leaving, nearly free when he said it.

“I don’t know what I ever did to you, Kathy.”

He spat my name — the one he gave me after first denying paternity — like a curse word.

This meeting was a misguided throwback to more than 30 years ago when he and my stepmother gathered my two older brothers, two older stepbrothers and I in another Forest Park family room to either introduce/lay down house rules, assess new fines for old ones or add a nuance to an existing chore. (The steps are now to be swept with a small whisk broom.)

It was the pitfalls and realities of raising a blended gaggle of teenagers with multiple parents.

It was a train wreck.

My father and I diverged when he stopped parenting me — really connecting — when I was 13: the year I got my period, started 8th grade, battled my oily, acne-prone skin, a funny-built body and unreasonable hair; the same year he ceremoniously moved my soon-to-be new stepmother and her kids into our home with an early Saturday morning announcement/yelp that we were “moving the Graysons!” that day.

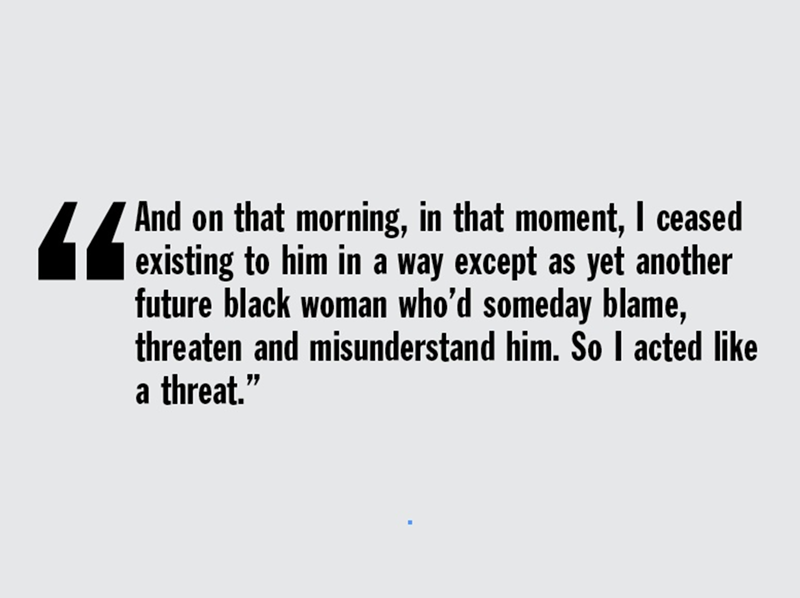

And on that morning, in that moment, I ceased existing to him in a way except as yet another future black woman who’d someday blame, threaten and misunderstand him. So I acted like a threat: I mouthed off in defiance (within an inch of punishment) and holed myself in my room, a protective cave against the bluster of stinky, over-sexed, sometimes violent boys to men and the (step)father who merely wanted us all out of his house on the other side.

I recently recalled this “family meeting” to my visiting sister (from a different father). It was the first time. I’d put it behind me as yet another failed drive-by on the resuscitation of any connection with my surviving parent. When I return from these trips I always land on what I learned late in therapy after my mother’s death. I do not have to ever lay eyes on my father again to reconcile with him. That piece of peace is mine. Intellectually I know this, but my mother taught me the biblical love of honoring my mother and father so I am somewhere in the forward slash between daughter/woman.

This column is not an axe and these words do not grind; they liberate.

When our mother died in 2005 I felt instantly parentless.

I am.

Where Mom was an action verb — parenting literally until her last, intensive care unit-breath — my father has long been a figurehead: the father, grandfather and great-grandfather who’s emotionally stilted yet paradoxically emotionally demanding especially when he is physically absent.

In the thicket of some of my family’s most emotionally and physically volatile memories, everyone’s version of events gets told and there’s never a mention or consideration of the effects of sexual deviance, spontaneous fist fights and the prolific presence of pornography on this former girl child.

Instead of providing protection and guidance, my father, a hard worker, sure, but a shadowy presence, nonetheless, was sometimes the cause and origin of that mess.

One good thing came of all that back then: I tearfully promised myself I’d never be rendered invisible or silent again.

I do have my mother to thank for that. She told me to speak up, ask questions when I didn’t know the answers and give the answer when I did.

I do have my father to thank for “choosing” my mother in, I think, 1958.

Of all the women he laid hands on in varying degrees, Mom was the best. And I do speak for my brothers, Randy and Kenny.

We came from these two parents in the picture that keeps catching my eye. We are good people.

So Happy Father’s Day, Randy and Kenny.

And to all black fathers and their daughters.

CONTACT KATHY Y. WILSON: [email protected]