F

or two days this month — Oct. 23 and 24 — Cincinnati will celebrate the glory of Robert Mapplethorpe’s art and life.Mapplethorpe + 25, a symposium sponsored by FotoFocus and the Contemporary Arts Center, will commemorate the 25th anniversary of the landmark traveling retrospective of the photographer’s work, The Perfect Moment, coming to the CAC. (Mapplethorpe died in 1989 of AIDS-related complications at age 42, not long after the show’s opening at the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute of Contemporary Art, whose Janet Kardon had curated it.)

Appearing at the symposium will be those who have curated, studied, collected and/or been inspired by his work, including Michael Ward Stout, president of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; Catherine Opie, a top contemporary art photographer influenced by Mapplethorpe’s work; and two photography curators working together on a 2016 Mapplethorpe retrospective, Britt Salvesen of Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Paul Martineau of the J. Paul Getty Museum.The symposium, which begins Oct. 23 with a 6 p.m. reception followed by a 7 p.m. keynote lecture by independent curator Germano Celant, will be free and open to the public. Reservations are requested at mapplethorpe25.org. (A detailed story on all symposium activities ran in the Oct. 7 issue of CityBeat; you can read it at citybeat.com.)

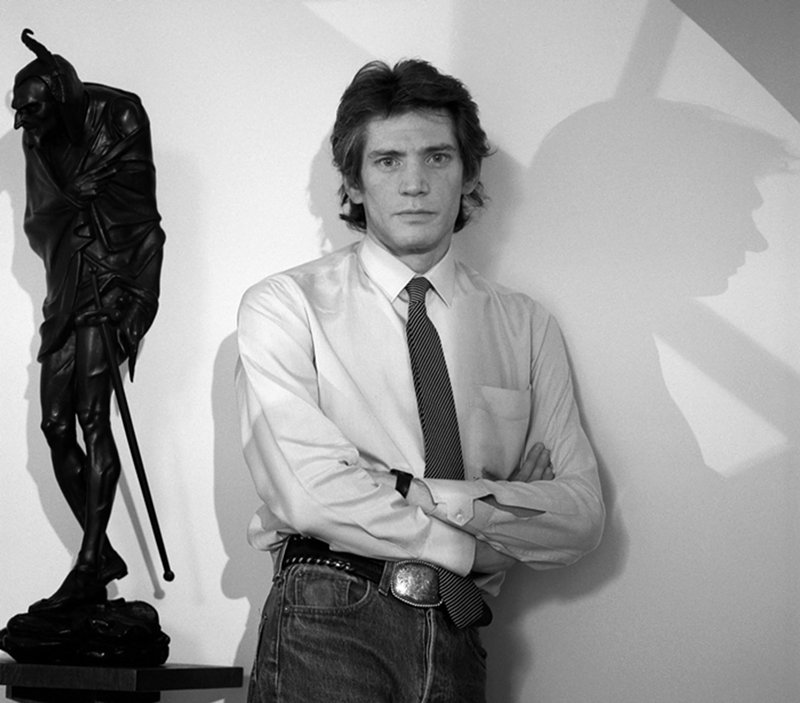

Even before he died, Mapplethorpe was a major name in contemporary photography — although not so known outside of it. In 1988, the Whitney Museum held a retrospective ahead of the touring Perfect Moment.

Now, he is firmly ensconced as a giant of art photography for the smoothly beautiful and contemplative classicism of his images of flowers, statues, nude models and the human face (including his), coupled with creative interplay between light and shadow and sometimes infused with eroticism. Indeed, Mapplethorpe is credited with playing a key role in getting photography accepted as a key part of contemporary fine art.His black-and-white photographs of flowers, especially, have become as ubiquitous as Andy Warhol’s art. “I go to the Bank of America here in L.A. and what’s behind the front desk but Mapplethorpe flower photographs?” Ohio-born photographer Opie says.

Really, he’s even more than an art-world presence — now he’s a cultural hero. Musician Patti Smith’s best-selling memoir about her relationship with Mapplethorpe in 1970s New York, 2010’s Just Kids, made him inspirational to many who never knew his art. In August, Showtime announced it would present a miniseries based on the book. And rival HBO has an upcoming documentary about Mapplethorpe planned for next year.

Further, he’s proved a particular inspiration to gay artists seeking mainstream success on their own terms. “He was a huge influence for a generation of young gays and lesbians who grew up with his work,” says Opie, who counts herself as someone inspired by Mapplethorpe.

So it makes perfect sense for there to be a symposium devoted to ongoing scholarship about him. On the other hand, it’s extraordinary that it’s being held here. His legacy includes a series of photographs, known as the X Portfolio, made in late 1970s New York. In those photos, he portrayed homosexual sadomasochistic acts. (Mapplethorpe, at the time, immersed himself in that male S&M subculture.)

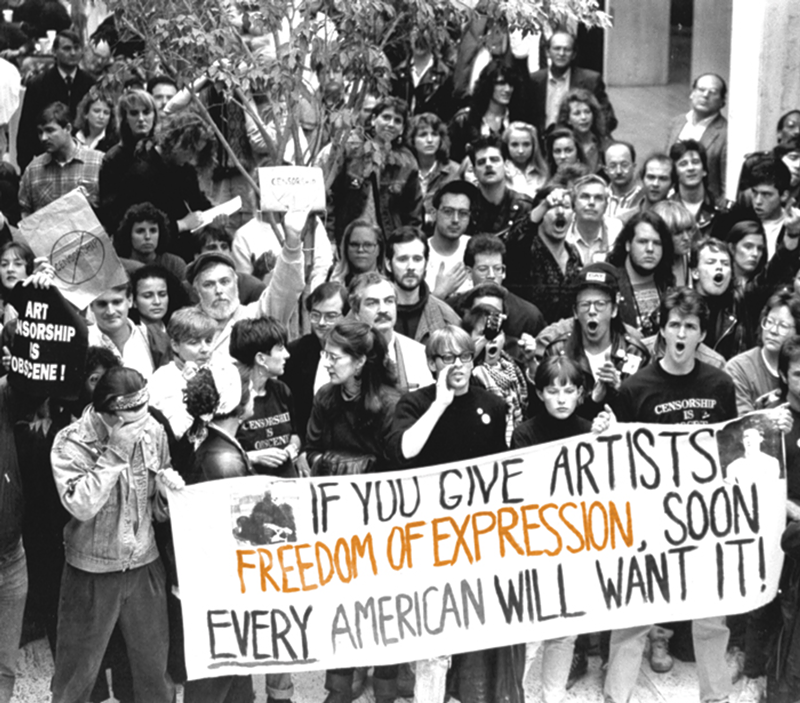

Because a smattering of that work was included in The Perfect Moment, the show became controversial at that time. Rightwing “culture warriors” attacked the federal National Endowment for the Arts for funding its catalogue, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. dropped the show.

In Cincinnati, where anti-“pornography” hunting had long been a rallying issue for conservatives, now-retired Hamilton County Sheriff Simon Leis and now-deceased prosecutor Arthur Ney — with support from the pressure group Citizens for Community Values — tried in vain to fight Mapplethorpe. They brought criminal obscenity charges against the CAC and its then-director, Dennis Barrie, for showing seven Mapplethorpe photographs — five from the X Portfolio and two unrelated commissioned portraits of naked or partially clothed children.

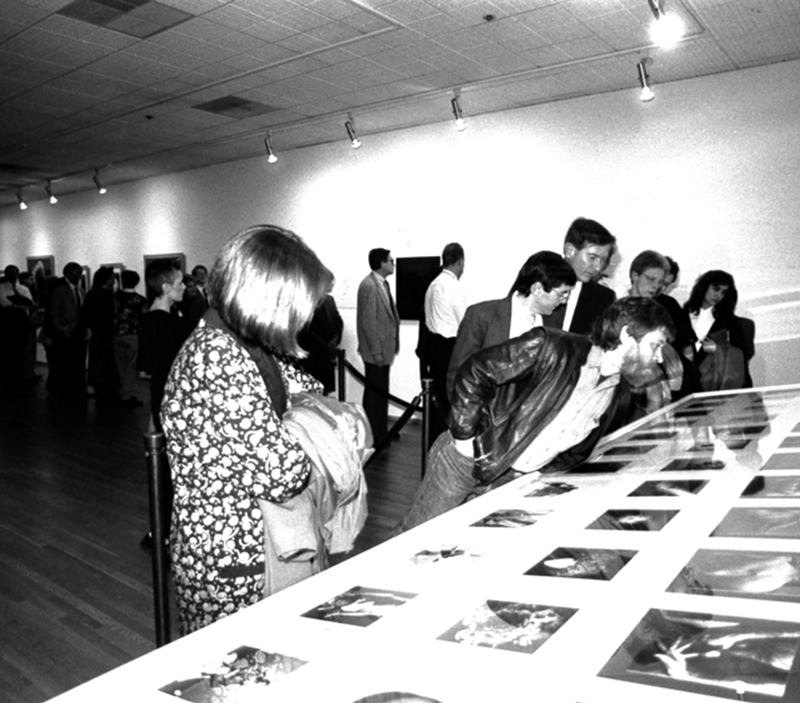

This prosecution was pursued despite the fact the show seemed constitutionally protected on the face of it — it had serious artistic value because it was organized by an arm of an Ivy League university and had already been shown in other art museums. Also, the attendance seemed to show that “community values” accepted Mapplethorpe’s work as art: 81,000 saw the exhibit during its run; a then-record 4,000 came to the preview.

In October of 1990 — 25 years ago this month — a Municipal Court jury took just two hours to acquit the CAC and Barrie of all charges. That makes this symposium, thus, an observation of an important victory against attempted censorship of the arts. “We’ve known for some time we wanted to do an in-depth symposium around Mapplethorpe because it was an important opportunity and almost our responsibility to think about this event,” says Raphaela Platow, current director of the CAC.But it’s also a recognition of the fact that in the art world, Mapplethorpe has long since ceased to be so controversial. The symposium aims to show just how accepted he is now.“The symposium angles very much to be about Mapplethorpe — the man and his work — to try to clear the smoke on the controversy and get back to an art-historical discussion on the significance of his pictures and what his work was about,” says Kevin Moore, FotoFocus’ artistic director, who selected the symposium participants with CAC approval.

“Back then, it was all about censorship and the scandal that occurred,” he says. “We’re trying to steer the conversation toward what

the work was really about, and include the controversy in the historical context.”

Platow agrees: “We really, really wanted to focus on Mapplethorpe as an artist and his legacy,” she says.

Still, it isn’t that easy to move forward. So the first symposium on Oct. 24 will be “The Exhibition, the Contemporary Arts Center, and Arts Censorship.” It will include Barrie, now based in Cleveland; Jock Reynolds, director of the Yale University Art Gallery; H. Louis Sirkin, trial counsel to Barrie and CAC in 1990; and Michael Ward

Stout, president of the Robert Mapplethorpe

Foundation. Platow will moderate.

Two questions that may well be posed at that symposium are: How has Cincinnati changed since 1990, and could a prosecution against an art museum happen here again? Opinions differ.

“I don’t think it could happen again,” says Barrie, who recently visited friends in Cincinnati and toured the vibrantly hip, revived Over-the-Rhine area. “I think so many things have changed in Cincinnati. With the demise of certain characters on the scene, the city feels more free and more able to accept change and different ideas.”

Sirkin is more cautious. “I think it could happen again,” he says. “They (the pro-prosecution forces) say they won the battle because they exposed it. They take pride in the sweat Dennis went through while that thing was pending.”

Oddly, one devil’s advocate on the panel could be Stout, whose foundation has done much to promulgate Mapplethorpe’s good name through its support of contemporary art photography in museums and of medical research into AIDS and HIV infection. (Mapplethorpe established the foundation shortly before he died.) The foundation’s income comes through the sale of his prints.

“I regret they (the symposium organizers) haven’t been able to invite someone from that (other) side,” Stout says. “It looks to me the lineup is pretty much all pro-Mapple-thorpe or pro-CAC. It would be interesting

if there were someone conservative.”

“I’ll bet there are people on the other side who don’t think this is settled,” he continues. “I’m sure there are people throughout this country that believe some of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work is not necessary to see publically, or be in public institutions or institutions that are tax-supported.” (He emphasizes he’s not one of them.)

Former Sheriff Leis did not reply to a request for comment by this story’s deadline.

There is an “oral history” component to the symposium occurring at the 21c Museum Hotel on Oct. 24, when all interested parties, no matter their viewpoint, are invited to share their memories of The Perfect Moment’s 1990 Cincinnati presentation.

Another important question to be explored at the symposium pertains to how the X Portfolio’s reputation has fared with time — very well, actually.

Between 1978 and 1981, Mapplethorpe produced the X, Y and Z portfolios. Each had black-and-white images pertaining to one subject — the S&M imagery of X , flowers of Y and nude African-American models in Z .The X images were pretty shocking. The New York Times described them this way at the time of the Cincinnati acquittal: “One of the five photographs shows a man urinating into another man’s mouth, another shows a finger inserted into a penis, and the other three each depict a man with an object inserted in the rectum: a whip, a cylinder, and a man’s hand and forearm.”

Among art followers, there is acceptance now of that as groundbreaking — a milestone even. The shock is gone.“Young artists interested in his work absorb it in a different way,” says Jennifer Blessing, senior curator of photography at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She will be at the Oct. 24 “Curators Curate Mapplethorpe” panel, which Moore will be moderating, along with Salvesen and Martineau.

“It’s less of a challenge to them,” Blessing says. “They see, I think, an artist who was really in love with the craft of photography and trying to create images for himself and his community.” By that, she says, she means the community of gay people who also enjoyed the S&M world. (The Guggenheim is planning a 2018 Mapplethorpe show, based on its trove of some 200 photographs acquired in the 1990s.)

One advocate of the X Portfolio’s place of importance is the aforementioned Salvesen, curator of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Besides the 2016 Mapplethorpe retrospective that she is organizing with the Getty’s Martineau, in 2012 she mounted an exhibit called XYZ containing all 39 images from the three portfolios.

“We had only one gallery and we installed X, Y and Z together on the walls,” she says. “We explored other options, but ended up showing them in three rows because that was the way Mapplethorpe talked about showing it.”

“He felt they were mutually reinforcing subjects and he didn’t want them to be seen in isolation,” she explains. “He wanted it to be understood that, whether it was a portrait or a floral still life or a sex picture, he approached it with equal sensibility and his own vision. He didn’t want them syphoned off into different categories.”

Actually, there is some Mapplethorpe work that has gotten more controversial with time. His use of nude African-American models, in the Z Portfolio and afterward, has come under increased discussion and analysis. That’s even as they become ever more popular — one of his photos in The Perfect Moment, 1980’s “Man in a Polyester Suit,” with its depiction of man wearing a suit but exposing his penis, just sold at auction for $478,000.

LACMA and the Getty intend to address that subject in next year’s retrospective.

“They are pictures that are very much as the artist would have us believe — they are about beauty, contrast, the idealized body,” Salvesen says. “But then there are other issues to confront about the fact of a white male photographer setting up these situations in the studio. Who did he intend the viewers to be? How can we as viewers acknowledge and appreciate the beauty without overlooking any power disparities or (other) issues of that nature?”

Perhaps the most personal and intimate

testimonial will come from Robert Sherman,

who is participating in the Oct. 24 “The Artist’s Circle and Studio” panel.If you don’t know the name, you may recognize the face. He is the hairless white man seen in profile, in front of an equally hairless black man, in the 1984 photograph “Ken Moody and Robert Sherman.” One of Mapplethorpe’s most famous and admired images, it was on the 1990 poster for The Perfect Moment ’s presentation at CAC. Both men had alopecia, and Sherman had hopes of an acting career around that time, though not as a leading man. “But he saw me in a light I couldn’t see myself in,” Sherman says of Mapplethorpe. “People see beauty in different ways. He just showed it to the world, and fortunately the world agreed.”MAPPLETHORPE + 25 SYMPOSIUM precedes the CAC’s exhibit, After the Moment: Reflections on Robert Mapplethorpe, opening Nov. 6. More info: contemporaryartscenter.org.