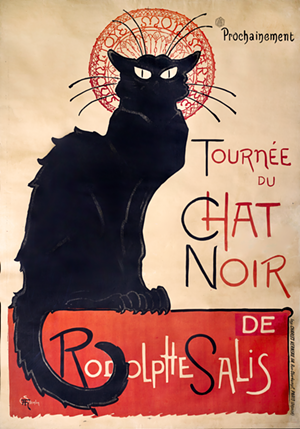

An overwhelming defeat in the Franco-Prussian War behind them, the French bourgeoisie and elites were blessed with four decades’ worth of regional peace and economic prosperity. With this Belle Époque (or “Beautiful Era”) came an influx of leisure time in which Paris’ rich and nouveau riche enthusiastically indulged. Unsurprisingly, great strides in the world of advertising coincided with this economic and cultural boom, as lavishly illustrated affiches (“posters”) were plastered on any available surface, marketing everything from bicycles to cabaret performances.

L’affichomania: The Passion for French Posters debuted at the Taft Museum of Art June 8, kicking off a seven-stop nationwide tour. Featuring five artists — Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Alphonse Mucha, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — the exhibition gathers the era’s iconic prints while demonstrating surprising stylistic diversity. The vibrant celebrity portraits of Chéret and Toulouse-Lautrec are instantly recognizable, making Mucha’s intricately detailed Art Nouveau works and Grasset’s vaguely Medieval forest scenes worth extra examination.

“The Belle Époque was the rise of entertainment — the opening of cabarets like Moulin Rouge or Le Chat Noir,” says assistant curator Ann Glasscock. “It’s partly due to electricity. If you think about it, (Thomas) Edison invented the lightbulb in 1879, and so (performers) like Loie Fuller are using colored electric lights. There are also world’s fairs that are also happening, drawing people to France. By the big one in 1900, the French, especially in Paris, saw themselves as the capital of the world."

Appropriately, a lithographic print of Fuller in action greets visitors at the start of the exhibition. Grouped with Jules Chéret’s body of work, “Folies-Bergère, La Loïe Fuller” exemplifies the father of the modern poster’s style — liquid whirls of movement and primary colors envelop his subject, suggesting billowing fabrics and brilliant lights against a black backdrop. Slouched bubble letters spell out the performance’s location in bright red. Even in the late 19th century, advertisers were well aware of the color’s ability to invoke passion, especially when paired with illustrations that exploited the male gaze.

Toulouse-Lautrec, whose work closes the gallery, was such a fan of Chéret’s that he would often send him the first edition of each poster he designed. The exhibition’s print of “Moulin Rouge,” addressed to Chéret in the bottom right corner, is one of the more striking pieces, thanks to its acidic green color palette and ominous use of shadow. Toulouse-Lautrec’s “Ault & Wiborg Co.: The Concert,” the final print on display, was commissioned in 1896 by Cincinnati’s Ault & Wiborg ink company, whose Strobridge Red ink attained international popularity due to its sun-resistant vibrancy. (That’s the same Ault who helped develop Mount Lookout’s Ault Park.)

Czech illustrator Mucha is the exhibition’s outlier, and his work is the most engaging up close. Tinged with pale lavender and turquoise, his work is densely populated with symbolism and flora, much of it depicting actress Sarah Bernhardt, who served as the Renaissance Theatre’s director from 1893 to 1899.

“She’s a pretty amazing figure,” says Glasscock. “She actually performed in Cincinnati on an American tour.”

A decorative arts historian, Glasscock is particularly fond of Mucha’s work.

“We often consider him a decorative artist,” she says. “He grew up in Moravia, around a lot of folk art and women who were making these Moravian bonnets — you can see one in one of the posters. They’re richly patterned, highly decorative.”

It’s that sort of recognizable style that helped Paris’s best-known artists rise to fame, especially during a period in which posters were hung nearly everywhere: outside venues, on specially-designated walls and tall, cylindrical structures known as Morris columns. One of these columns is on display in the Taft’s entrance, as part of the L’affichomania tour.

The Taft has also planned a number of events: Curator Jeannine Falino will give a talk on the Belle Époque on June 27, Cincinnati-based designer James Billiter will host a screen-printing workshop on July 27 and illustrator Erin Barker will teach a class on hand-lettering on Aug. 3.

L’affichomania: The Passion for French Posters will be on display at the Taft Museum of Art through Sept. 14. More info: taftmuseum.org.