At over six feet tall, Joseph Winterhalter is an imposing figure. With a deep voice and a firm handshake, he comes across as a fusion between an aging punk rocker and radical intellectual with a lot on his mind. At a recent gallery talk, I witnessed him expounding upon everything from Post-Structuralism’s emphasis on binary tensions to the machinations of the state-corporate nexus.

The Revolution Says…, his new exhibition of prints and paintings at Clay Street Press, is a potent cocktail of social commentary and political agitation that explores ideological and institutional failure. But in contrast to the incendiary politics that inform his work, the show is a slow burn.

I didn’t like it at first. The exhibition’s five lithographs are implacably cerebral and possess an almost vehement disregard for aesthetic concerns. According to Winterhalter, the prints, which sample the iconography of Marxist-inspired revolutionary groups like the Weather Underground, Red Army Faction and the Situationist International, are an attempt to “provide context for the paintings.” In that regard, they do operate as a kind of visual artist’s statement. But their literalness renders them difficult to encounter as art.

Winterhalter’s painting is another matter. A subtle and sophisticated thing, the large-scale works that anchor the exhibition reward a patient eye with an outpouring of mischief.

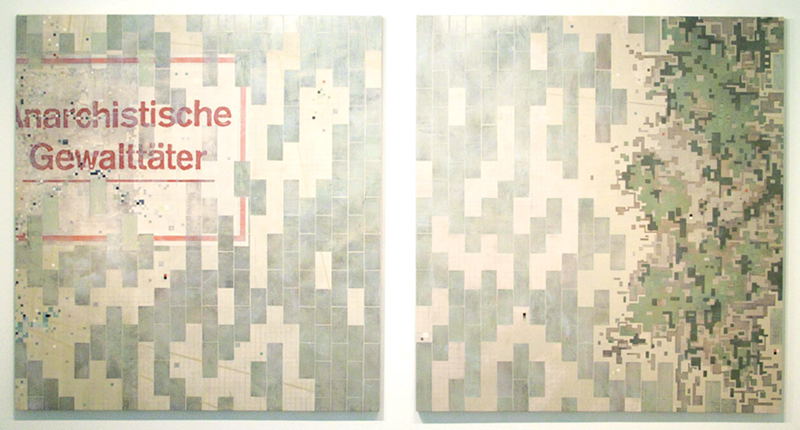

The diptych “Dissemination…Under the Big Black Sun” is a marvel of conceptual and pictorial tensions. Just slightly off square, the 78-inch-tall paintings mine the traditions of early 20th century geometric abstraction, quoting Russian Suprematists in a palette of battleship grays and institutional greens.

Using a faint blue grid reminiscent of European notepaper to guide him, Winterhalter deploys a series of slick “subway” tiles that jostle across the surface of his canvases. These tiles are laboriously painted, scrapped down and painted again using a patent concoction of acrylic paint, latex, resin, oil and wax. The result is a jewel-like finish that shimmers as you navigate the gallery.

True to their roots in 20th century French thought, the works revel in contradictions — the paintings are simultaneously illusory windows into an alternate reality and sculptural objects protruding into our own world.

When the tiles densely congregate along the sides of the paintings, they flatten out and wrap around the edge, emphasizing the works’ surface and creating a sculptural presence.

Moving away from the edges, the tiles open up and spread apart. A blood-red depiction of the phrase Anarchistische Gewalttäter — “anarchist criminals” — floats in like a wanted poster. A tactic developed by Picasso collaborator Georges Braque, the use of text affirms the painting’s surface, pushes the tiles beneath it into a fictional third dimension, and disrupts the painting’s read as sculpture.

Winterhalter’s other large painting, the camouflage-laden “More fun in the new world” is similar in scope and style, but its blue-grey surface is more taut which leaves little room the perceptual gymnastics that is the diptych’s strength.

Both paintings emphasize rectilinear shape recalling the monumental (and moribund) architecture that still dominates urban centers in the former Soviet bloc. A sort of international style from hell, these buildings are bleak reminders of everything that went wrong with the great “socialist” experiment.

During his artist’s talk, Winterhalter described his paintings as “depictions of failed possibilities.” But I wonder if they’re not allegories for the world we live in today.

One of history’s great ironies is that the Orwellian perversions of fact and language long associated with the repression of the former Soviet Union are equally at home in the capitalist “free world.” Here, a bureaucratic language of newspeak is supplanted by a corporatized free-market doublespeak.

Our national dialogue is peppered with phrases such as death tax, creation science, right to work and rightsizing that, like Soviet propaganda, are deliberately designed to misinform and ultimately manipulate a populace too distracted by the latest YouTube video to care.

Seen in this light, The Revolution Says… isn’t just a meditation on the failure of 20th century-isms to address the liberation of man. It’s an indictment of contemporary free-market pathologies that have colonized our mental conceptions, imprisoning us in a world where freedom has been narrowly defined as a choice among provided options. The rigidity of Winterhalter’s ubiquitous geometry is not a visual relic of some doomed authoritarian past, but rather a stark warning about our present inclinations.

THE REVOLUTION SAYS… continues through May 19 at Clay Street Press in Over-the-Rhine.