S

eteria Carter of North College Hill has been battling cancer for four years. An intense regimen of chemotherapy and attendant complications caused her to drop out of school, where she was training to be a medical assistant, and has kept her from working. In that time, she’s relied on federal food assistance from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, often called food stamps.

“They’ve helped me tremendously,” she says. “They’re really a godsend. If I didn’t get food stamps, I wouldn’t be able to eat.”

Carter is one of more than 125,000 people in Hamilton County who receive SNAP benefits. But there are others in the county — and in urban areas across the state — who need them and don’t get them. That’s in part due to a decision by Ohio Gov. John Kasich not to apply for federal waivers for work requirements on SNAP benefits in those areas, even though they meet federal guidelines for such exceptions. The areas, including Hamilton County, have high percentages of low-income and minority residents, some of whom could have stayed on the assistance if not for the decision to forgo federal waivers.

In Hamilton County, 18,000 people must now meet work requirements in order to access food aid thanks to the decision, and in areas where economic opportunity still lags, many go without. Across the state, more than 140,000 people have fallen off the food stamp rolls due to the change.

Kasich points to the economic recovery in Ohio as a reason for his decision. The state’s unemployment rate has lowered to 5.2 percent, and Ohio has added 95,000 jobs in the last year. But the state still ranks low nationally in economic outlook. A study by the Arizona State University W.P. Carey School of Business found the state 29th in the nation in terms of number of jobs and job growth. Further, the recovery here has been unequal in lifting up Ohioans — data shows that customers at food pantries in the state rose 40 percent between 2010 and 2014, and Ohio still ranks sixth in the nation in terms of food insecurity.

“The economic recovery hasn’t reached a lot of people who have been unemployed for a very long time, people who are working but at a very low-wage job, people working multiple part-time jobs,” says Freestore Foodbank Director of Strategic Initiatives Jennifer Steele. “We’re still seeing an increasing need.”

The Freestore serves thousands in a 20-county region. The nonprofit helps Hamilton County residents like Carter apply for SNAP benefits, assisting them through the maze of applications and documentation they must complete. The Freestore also runs its own food pantries and works with more than 250 partner organizations throughout the region.

Steele says those hardest hit by the lack of waivers are clients who might meet the highly technical federal definition of able-bodied, but who struggle to find or keep work.

“Our partners across the region started reporting higher numbers once the waivers went away,” Steele says. “It’s especially prevalent in individuals who are suffering from mental illness and other disabilities. The issue is a lot of times that someone is mentally ill but hasn’t seen a psychiatrist to get the appropriate diagnosis. So as far as the state is concerned, they’re able-bodied, but they have a very real disability and they’re living with it and it’s impacting their ability to work.”

Many of the areas eligible for the waivers denied by the Kasich administration have high concentrations of black residents, which has sparked outcry and a civil rights lawsuit last year by Legal Aid Society of Columbus. Ohio lawmakers, including U.S. Rep. Marcia Fudge, have pushed courts to rule on that lawsuit. Areas of Fudge’s district in Cleveland have some of the highest poverty levels in the state.

“I’ve heard the stories from my constituents who struggle each month to pay for basic necessities such as medicine and food,” Fudge wrote in a letter to Kasich earlier this year. “Without question, Ohio should take advantage of every opportunity to mitigate these challenges and feed those in need.”

The Ohio Department of Health and Human Services says counties are selected by highest unemployment percentage. But by sheer numbers, the large urban areas not covered by Ohio’s decision have far more unemployed people than the rural areas the Kasich administration selected.

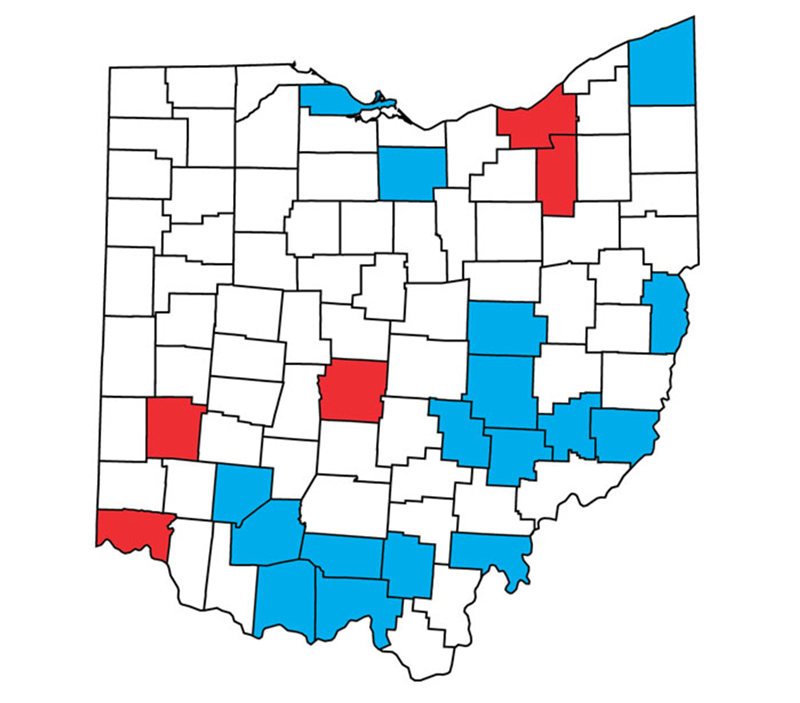

According to a CityBeat analysis of Sept. 2015 unemployment data, the 17 sparsely populated Ohio counties that received federal work requirement waivers for SNAP this year contain about 42,000 unemployed people.

Meanwhile, the state’s five largest counties, all predominantly urban, contain 187,000 unemployed people. These include Cuyahoga County, which is 30-percent black, Hamilton County, which is 26-percent black and Franklin County, which is 22 -percent black. None received waivers.

Nine of the 17 counties which Kasich has granted waivers are 1-percent black or less. Last year, nearly 95 percent of waiver recipients in counties granted them were white, according to state data. That’s despite the fact that statewide, almost 38 percent of overall SNAP recipients are minorities.

“One of the unintended consequences was that cities were largely excluded,” Steele says of the way Ohio applied for its waivers. “Minorities were disproportionately impacted by the waiver applications because they largely live in cities.”

Under current federal law, able-bodied adults are eligible for three months of benefits every 36 months unless they’re working at least 20 hours a week. But during the Great Recession, the government issued waivers to this rule for states with higher-than-average unemployment.

Kasich first made the decision to selectively apply for the waivers in 2013. That year, the entire state qualified for them, but the governor only applied for them for 16 mostly rural, nearly all-white counties. The Republican, who is now running for his party’s presidential nomination, said he did so in an effort to practice fiscal responsibility and end dependence on the program, and because the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services is more active in urban areas and can help in other ways.

Though statewide exemptions will end in 2016, 32 counties and 12 cities in Ohio are still eligible for waivers by the federal guidelines. However, Kasich recently announced the state would again apply for 18 waivers for the same mostly rural, predominantly white counties, with a few additions and subtractions. Cities like Dayton and Cleveland have passed resolutions asking Kasich to apply for the waivers for their low-income populations.

Work requirements for able-bodied adults were part of bipartisan welfare-reform legislation co-sponsored by then-congressman Kasich in the 1990s. They were designed to limit time spent on federal aid programs, which conservatives say bred a cycle of dependence.

That narrative has become a major theme in Republican politics and part of larger calls to slash government spending. Powerful party leaders like U.S. Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin have pushed budgets that cut food-aid spending, arguing that cultural factors have led to cycles of poverty and dependence on government aid in America’s inner cities. Federal nutrition programs have weathered a number of cuts in Congress over the past few years as Ryan and others have chipped away at SNAP spending.

But studies of welfare users, including a large-scale study released last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research, show most people on welfare programs like SNAP stay on them for short, finite amounts of time and suggest the programs don’t cause dependence. Nutrition programs are also a very small part of the federal budget, accounting for less than 1 percent of overall government spending.

Meanwhile, Kasich is pushing hard on both his conservative credentials and his compassion as he campaigns for the GOP presidential nomination, set to be decided next year in Cleveland.

The governor has quoted Bible verses extolling care for the poor in campaign stops and interviews.

“Did you feed the hungry? Did you clothe the naked? If we’re doing things like that, to me that is conservatism,” he said during a Fox News interview in late January.

But that help comes with a time limit, according to Kasich’s campaign.

“If anybody out there believes that able-bodied workers between 18 and 49 should be on benefits indefinitely, then that is just fundamentally a difference of opinion,” Kasich campaign spokesman Rob Nichols told the Cleveland Plain Dealer earlier this month, dismissing criticisms against Kasich’s SNAP policies as “insipid politics.” ©