By the late-2000s, the merits of investing in urban cycling infrastructure were well known outside of Cincinnati. Places like Portland, San Francisco and Chicago had proven that, if you build it, bike riders would come, and many mid-sized cities were beginning to enjoy a safer biking culture for the growing number of new urbanites choosing to live a car-free lifestyle.

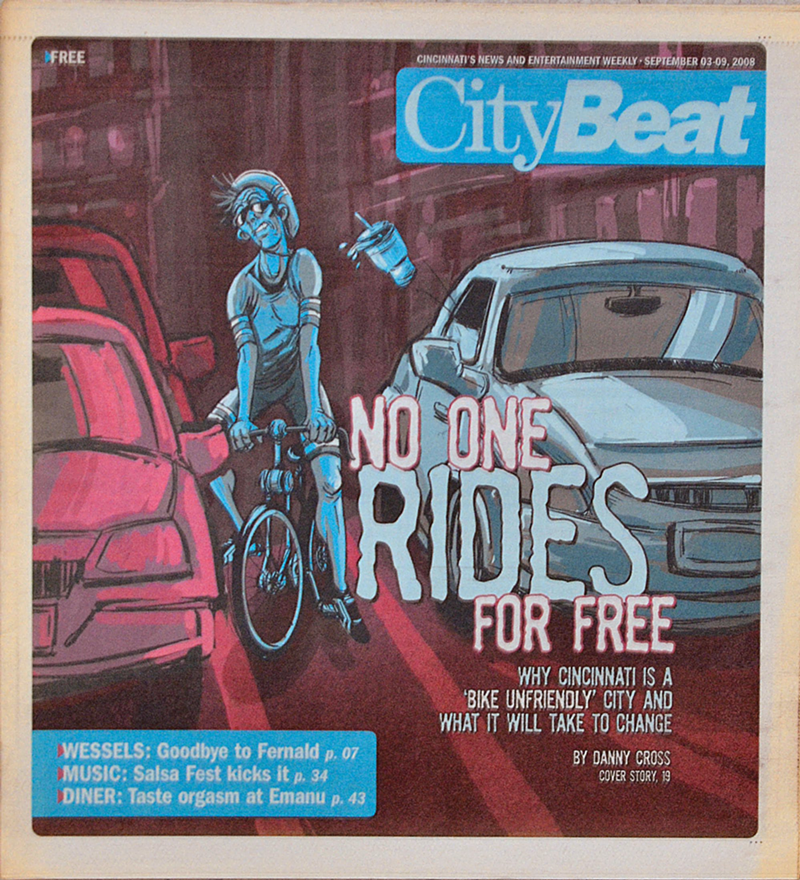

Cincinnati, as is often the historical case, was behind. The city was named to the League of American Bicyclists’ list of “Not So Bicyclist Friendly” cities in 2007 and had seen little movement on a collection of bike plans going back 30 years. Cincinnati’s most recent bike route guide at the time was a decade old and relatively useless, as cyclists actually avoided many of the official “Signed Bike Routes” because of heavy traffic, high speed limits and freeway ramps entering shared roads. The 1976 Cincinnati Bikeway Plan was still theoretically guiding new infrastructure projects, but it was non-binding and relied mostly on new construction projects for any change.

While Cincinnati allocated a measly $75,000 to $150,000 per year to bike projects, Portland was kicking 1.7 percent of its capital budget to bike planning, combining the simplest of devices — the shared street — with wide bike lanes, bike paths and bike boulevards (roads completely closed to cars) to create a system functional and safe for bikes, cars and pedestrians. The benefits went beyond allowing a small hippie segment of the population to exercise on the way to work; Portland officials credited traffic-calming measures with helping to reduce the number of motor vehicle driver or passenger deaths from 41 in 1996 to 15 in 2007. All while daily bike ridership continued to rise.

Even without being all-in like Portland, nearby cities like Louisville and Columbus were far more dedicated to bikes than Cincinnati. Various factions of local cycling advocates were pushing for attention, and the solution was relatively simple: Cincinnati needed to prioritize cycling infrastructure in policy — and then actually fund the improvements — or it would miss out on a critical stage of building a safer, more bikable and walkable urban core.

Excerpt:

“ ‘Removing on-street parking is one of the real hot button issues,’ Coppock says. ‘We tried to do bike lanes on Central Parkway just north of Western Hills viaduct because there are three lanes going north and two south. I thought, “We can re-stripe this.” It’s one of our early attempts — it’s an assigned bike route, it was easy pickings. But the on-street parking was not negotiable.

“ ‘The property owners came into City Council with lawyers and said, “No, we’re not going to go quietly.” The same thing happened on Erie Avenue (in Hyde Park). We had to move a little bit of the bike lane on one side because of a property owner. We took away a parking space and they came in and protested. I don’t know how Portland deals with that.’ ”

Today:

Cincinnati has managed to build small patches of usable on-street infrastructure over the years, but a new Bicycle Transportation Plan City Council adopted in 2010 again is merely a set of suggestions. As recent history has proven, it does not have to be followed by the mayor or City Council.

Mayor John Cranley this year nearly scrapped a fully funded plan to install protected bike lanes along Central Parkway after complaints from a handful of businesses over the removal of on-street parking. Cranley paused on the project, but a compromise proposed by Vice Mayor David Man narrowly saved it — at an additional cost of $110,000.

During another vote, Cranley diverted funding from on-street infrastructure toward Cincinnati’s urban trail system in a controversial measure that also provided $1.1 million to start up Cincy Bike Share. Council members took the offer, although some also took exception to being forced to vote for the trail money — $800,000 toward four systems that will cost millions more to complete — just to keep the bike share afloat.

The Red Bike share system — which offers 300 bikes at 35 stations in the central business district, Over-the-Rhine and uptown — has been extremely popular. Ridership significantly outpaced expectations during its first month, suggesting that Cincinnatians are just as willing as anyone else to take advantage of safe and convenient cycling infrastructure if we ever find the guts to build it.