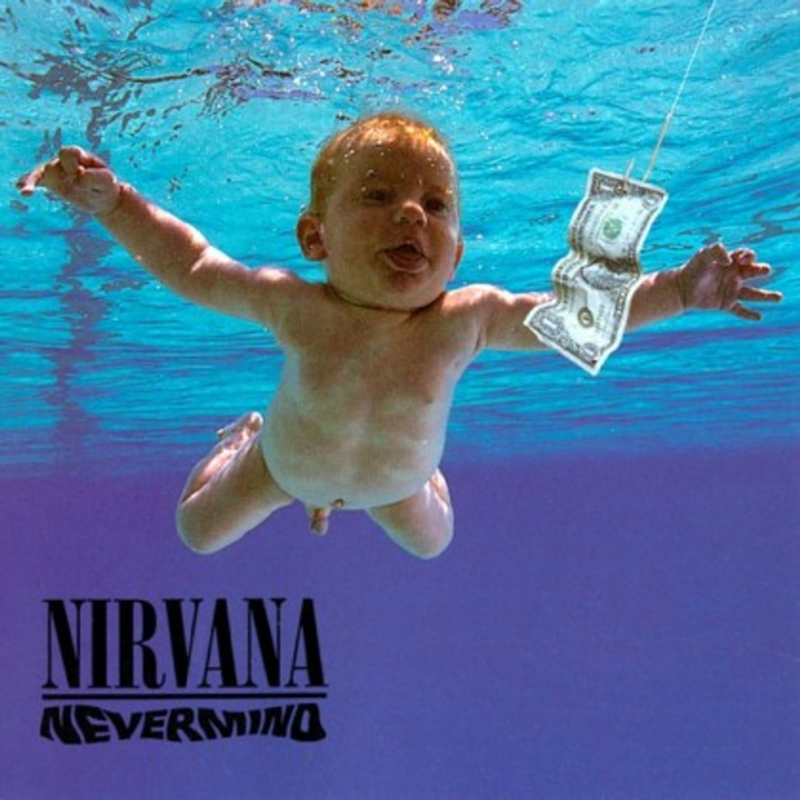

In 1991, Nirvana roared out of Northwest obscurity and into the global consciousness with Nevermind, an album of almost incomprehensible magnitude and influence. Three short, tempestuous years later, Kurt Cobain turned his back on his brief run and enormously potent legacy in a horrible, irrevocable act of abdication. Whether it was the mundane horror of heroin, the unflinching spotlight and endless treadmill of fame, a rudderless personal life spinning inexorably toward the drain or combinations of some or all or none of it, Cobain saw only one way out, a single-shot solution that solved everything and nothing.

The irony of Cobain’s final act is that Cobain, Grunge and Nirvana became even bigger than they had been. Cobain graced the covers of more music and pop culture magazines as a dead celebrity than a living bandleader, Alternative music in general and Grunge in particular grew exponentially as the once marginalized music was mainstreamed into a first language of disenfranchised teenagers. Nirvana ultimately became a platinum bone to be fought over by deserving dogs and ungrateful curs.

The ripples of Nirvana’s influence continue to radiate outward, 17 years after Cobain’s death. Consider this: In Cobain’s lifetime, Nirvana released three new studio albums, a demos/rarities collection, eight singles and a couple of EPs. Since his death, there have been three live albums, four compilations, five video/DVD releases and a box set.

And to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the release of Nevermind, Universal is adding to the catalog count by assembling three separate celebrations of the title, divided into a distinct yet inextricably connected triptych; a straight single disc remastered reissue, a deluxe two-disc edition including pre-Butch Vig demos, B-sides and other rarities, and a super deluxe five-disc package featuring original demos and mixes including the so-called “boombox rehearsals,” the unreleased 1991 Halloween concert at Seattle’s Paramount Theatre and a DVD of the same concert plus the band’s four music videos from the album and a 90-page book.

All of the various iterations of Nevermind may just have the strength to tap the same rich vein as their aforementioned predecessors, five of which sold in platinum (or higher) amounts. After all, Nevermind was one of the first albums to earn the newly established diamond certification in recognition of sales exceeding 10 million units, a mind-boggling number in the current atmosphere where 40,000 in first week sales gets you a spot in the Top 10. Nirvana’s propensity to debut in the No. 1 slot after the release of Nevermind may at last prove true for the album that started it all for the band in 1991, even if the actual amount of albums sold proves to be significantly less in the industry’s new economic reality.

And then, of course, there’s the music itself. Cobain took influences as disparate as Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Melvins, Pixies, The Meat Puppets and every band of note in the Seattle/Olympia scene in the late ’80s and created a beautifully dark cacophony that hybridized ponderous Rock and Metal with fleet Punk, visceral Garage Rock and incongruously melodic Pop. In the Nirvana crucible, Cobain mixed slashing, distorted guitar riffs and raggedly emotional vocals that veered wildly between whispers and howls, while bassist Krist Novaselic provided a rib-breaking heartbeat and drummer Dave Grohl anchored the tumult with a pulse that felt like tectonic slippage set to an unmistakable rhythm.

It’s difficult to look past the tragedy that Kurt Cobain never had the opportunity to evolve beyond the work he created between 1988 and 1994, and that his invaluable contributions to music will necessarily remain suspended in the amber of his self-inflicted short life. By the time Nevermind was released, he claimed that his increasing joy was moving his music away from Grunge’s bleak terrain and toward a brighter Pop future. What he might have done after the release of 1993’s In Utero is a matter of purest speculation, but it’s the safest bet at the window to say that whatever direction Kurt Cobain decided to pursue, the world would have followed. The proof of that is found in the fact that we’re still discussing, experiencing and reveling in his influence nearly a quarter century after he began, and in the astonishing realization that there remains an enormous and avid audience for his world altering creation.

Former Broken Social Scene vocalist Leslie Feist was one of the highest profile beneficiaries of the TV-is-the-new-radio paradigm when her insanely catchy single “1234,” from her third album The Reminder, struck gold for Apple. You might have been visualizing iPod nanos but you were singing, “Oh, whoa oh, you know who you are …”

The song subsequently inspired TV placement, remixes, remakes, a Sesame Street version and an American Idol cover, pushing the album into platinum sales figures and earning Feist five Grammy Awards and five Juno Awards in her native Canada, but there’s a potent downside to that kind of ubiquity; people identify so completely with one song they find it hard to accept anything else the artist does. As it happens, “1234” remains Feist’s only song to chart on Billboard’s Hot 100 and the UK Top 40.

Although it’s been four years since The Reminder, and while Feist stated that she would need to process her experiences before recording again, she’s hardly been in seclusion, touring consistently and collaborating with BSS, Beck, Wilco, Grizzly Bear and Ben Gibbard, among others, making various TV appearances and doing video work. With the release of Metals, Feist finally breaks her long studio silence and it shows that she followed the first commandment of following up a stratospheric album and single: “Thou shalt not try to duplicate the sound to capitalize on your last big success.”

On Metals, Feist plays up her funkier aspects with the New Orleans Pop of “How Come You Never Go There,” shows off her propulsive World chops with “A Commotion,” soothes with the blustery Jazz/noise balladry of “Anti-Pioneer” and the gypsy hymn stomp of “The Undiscovered First,” and captivates with the arty Pop lilt of “The Circle Married the Line.” The use of strings on Metals gives the album a Chamber Pop feel and the setting reinforces Feist’s numerous comparisons to Kate Bush, as does her occasional melodic yelp.

Metals may not ultimately be the cash cow that The Reminder and “1234” proved to be, but it clearly shows that Feist is more interested in musical artistry and creative growth than sales charts and mantle bling.

We Were Promised Jetpacks began eight years ago as the winning entrant in an Edinburgh high school band competition, sparking a move to Glasgow and widespread airplay based on a three-track demo. WWPJ’s full length debut, 2009’s These Four Walls, mixed frenetic Punk with bombastic Rock, inspiring references to early U2, Big Country and The Cure.

After last year’s muted EP, The Last Place You’ll Look, WWPJ returns to the moody and energetic sound of their debut with In the Pit of the Stomach, a ten-song set that bristles with raw Post-Punk power while pulsing with Pop subtlety. “Medicine” and ‘Boy in the Basement” are propulsive rockers reminiscent of Echo & the Bunnymen’s dark intensity with slightly shinier exteriors, while “Act on Impulse” motors along on insistent guitar/synth lines and tribal drums that wouldn’t sound out of place on a Smiths hit package.

Forget the old promises; these Jetpacks deliver the sky.

There aren’t many artists who are as evocative of the tumult, tragedy and triumph of the ’60s as Marianne Faithfull. Her name alone conjures up images of the daring sexual, chemical and musical limits that were being tested and toppled in those heady days. Faithfull’s exploits as a Pop singer and Mick Jagger’s girlfriend might seem prosaic by today’s jaundiced standards but she was a scandalous libertine three and a half decades ago, long before there was a map for navigating the treacherous waters of cultural experimentation or the unreasonable expectation of surviving them with career and sanity intact.

Since taming her demons in the ’70s, Faithfull has assembled an astonishingly diverse catalog filled with major accomplishments and minor excursions. Horses and High Heels, her 19th solo album, clearly stands with the former.

Faithfull’s voice, like Lauren Bacall on a whiskey-and-high-tar-cigarette regimen, is the perfect delivery vehicle for her written or chosen songs of weary reportage concerning the damaged human condition. Faithfull opens with a haunting cover of The Gutter Twins’ “The Stations,” which she reads as an epic interior monologue on wrestling with religion, mortality and the real and imagined sins we all face at the end, set to an eerie Gospel/Blues soundtrack. “Why Did We Have to Part,” one of Faithfull’s four co-writes, is an amazingly straightforward love-gone-wrong song, while her cover of R.B. Morris’ “That’s How Every Empire Falls” has the continental twang and swell of Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, telling the tale of a lost man and his search for personal and universal truth, his religious, legal and moral examinations of existence and the sanguine conclusion found in the title, a sentiment both beautiful and unsettling.

“No Reason,” a cover from obscure ’60s rocker Jackie Lomax’s Third album, is classic Stonesy Rock, and she turns Mickey and Sylvia’s “Gee Baby” into a honky-tonkin’ barroom Blues rave, while her cover of “Love Song,” written by Lesley Duncan and recorded by Elton John on his exquisite Tumbleweed Connection, has a quiet Pink Floydian elegance (perhaps a tribute to Duncan’s vocal contributions to Dark Side of the Moon).

Perhaps the album’s highlight is Faithfull’s take on Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s “Goin’ Back,” most prominently covered by the great Dusty Springfield, an unapologetic reflection on a long life, wistful but realistic and beautifully rendered as a baroque Pop piano ballad. Given her long history of style shifts, Horses and High Heels may not represent a full-blown direction for Marianne Faithfull, but the album’s outcome should indicate this would be a nice spot to settle for a little while, in any event.

On Eilen Jewell’s Queen of the Minor Key, her fourth album of original material, the Idaho-born/Boston-based singer/songwriter pushes her sound beyond the Country/Folk parameters she established for herself on her previous three (2005’s Boundary County, 2007’s excellent Letters from Sinners & StrangersSea of Tears). Bookended by the Surf/Spy thematics of opening instrumental “Radio City” and propulsive bikini beach closer “Kalimotxo,” Queen of the Minor Key finds Jewell expanding and refining her creative vision, from the slinky and seductive Jazz Folk of “I Remember You” to the mournful Country sway of “Santa Fe” to the ’50s horror movie tiki bar shimmy and twang of the slightly dangerous “Warning Signs” the uncharacteristic smirk and bounce of “Bang Bang Bang.” and 2009’s

Queen of the Minor Key also marks the first time that Jewell has featured outside vocalists on an album, and she’s instituted that policy with a captivating rookie and a bona fide ringer. The slowburn Country weeper “Over Again” offers gorgeous counterpart harmonies from Zoe Muth, whose career was kickstarted by Jewell (she got Muth signed to Signature Sounds and hooked her up with her booking agent after being wowed by Muth’s opening slot a couple of years back). Jewell and Muth work together like raw honey and homemade whiskey, and “Over Again” is evidence that this shouldn’t be a one-shot collaboration. Equally impressive is Jewell’s duet with Rockabilly Hall of Famer Big Sandy, who adds his distinctive croon to the Patsy Cline western swing of “Long Road.”

If there’s a message on Queen of the Minor Key, it may well be that Eilen Jewell is ready to go in any direction, and maybe every direction, and make them all work for her.

Eight years ago, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings released the exploratory and occasionally misunderstood Soul Journey, where Welch took a more directly personal stance in her writing as the duo injected a shade more vitality (and electricity) into their old-time musical presentation. Maybe the album’s mixed reviews had a negative impact on Welch, or maybe her creative well was lowered by a quartet of excellent albums over a seven-year period. In any event, Welch was beset by a writing block that short-circuited every attempt to conquer it; the trend was reversed in 2009 when the pair switched spots on the marquee and they released the well-received A Friend of a Friend as the Dave Rawlings Machine.

Subjugating her role in the duo must have been just the tonic for Welch, because The Harrow and the Harvest stands with the best of their work together. Like Soul Journey, The Harrow and the Harvest finds Welch writing as more of an active participant rather than detached observer, like the melancholy heartbreak victim in “Dark Turn of Mind” or the hard love/hard luck girl in “Tennessee.” The inevitable flow of life is a familiar theme for Welch on The Harrow and the Harvest, with a trio of songs offering interestingly similar titles and messages and distinct musical frames; the sad acceptance of “The Way It Will Be,” the jaunty and jaundiced “The Way It Goes” and the loping drawl of “The Way the Whole Thing Ends.”

The Harrow and the Harvest departs from Soul Journey, with Welch and Rawlings maintaining an acoustic profile but, like the best of their work to date, they modernize their Folk/Bluegrass texture with a contemporary lyrical perpective (“Becky Johnson bought the farm, put a needle in her arm/That’s the way that it goes, that’s the way”).

The songcraft and execution on The Harrow and the Harvest are high, which hopefully represents a revitalization of Welch’s bound muse and a faster turnaround for the next album.

It’s hard to remember that Dave Alvin’s critically acclaimed debut solo album, 1987’s Romeo’s Escape, was such a spectacular commercial disappointment that it got him dropped from his Columbia contract. It wasn’t until Dwight Yoakam had a hit with Alvin’s “Long White Cadillac” that the rootsy singer/songwriter could properly launch his solo career with 1991’s Blue Blvd and he’s been exploring the acoustic and electric possibilities of his noirish Rock/Folk/Country triangulation ever since.

The past decade has been the most exploratory; his 2000 covers album, Public Domain, won Alvin a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album, 2006’s West of the West celebrated California songwriters and 2009’s Dave Alvin and the Guilty Women was an excellent reconfiguration of his Guilty Men band.

Alvin’s latest, Eleven Eleven, named for his birth date, is a brilliant blend of the various styles he’s navigated over the past quarter century, and to create it, he ignored a lot of the parameters he’s followed in that time. Eleven Eleven was written on the road during the Guilty Women tour and recorded with musicians Alvin hasn’t worked with since his days with The Blasters in the mid-’80s. As a result, Eleven Eleven bristles with an intensity that’s impressive, even by Alvin’s standards, from the brooding menace of “Harlan County Line” to the Bo Diddley insistence of “Run Conejo Run” to the sexy Rock thump of “Dirty Nightgown” to the tragic smirk of the Blues-laced “Johnny Ace is Dead.”

Alvin’s duets on Eleven Eleven run the gamut of emotions and styles; “Manzanita” is a gorgeous Country breeze featuring Guilty Women vocalist Christy McWilson and “Two Lucky Bums” is a loping lighthearted romp that turns out to be lump-in-the-throat poignant as the last recorded collaboration between Alvin and best friend Chris Gaffney, who succumbed to liver cancer just after this session. The best of the three is the searing Blues of “What’s Up with Your Brother,” where Alvin and brother Phil sing together on an album for the very first time (Phil was sole vocalist in The Blasters), each bemoaning the fact that people always inquire about the other one. The brothers’ contentious history is played up to hilarious effect in a dialogue at song’s end when their conciliatory mood is dashed as old differences creep back into their reunion and Dave walks out as Phil notes, “See ya Thanksgiving.”

From blistering Roots Rock to stalking Blues to lilting Country to Tejano rhythms, Eleven Eleven is a sonic scrapbook of Dave Alvin’s triumphs over the past three decades, a greatest hits album of brand new songs that represent everything that Alvin has done well and better during the course of his perpetually interesting solo career.

From the beginning of his career four decades ago, Garland Jeffreys’ work has been laced with the realities of his New York upbringing, his African-American/Puerto Rican heritage and his subsequent unique perspective. Musically speaking, Jeffreys — who either enjoyed or endured comparisons to Lou Reed, a friend before his Velvet Underground years — assiduously avoided pigeonholing (and airplay) by cooking up a sonic stew that mirrored his melting pot environment, randomly flavoring his songs of social observation and outrage with Soul, Reggae, Pop, Rock and Blues.

Although Jeffreys found himself saddled with the unenviable tag of “Next Big Thing” early on, particularly after the high profile FM success of his anthemic single “Wild in the Streets,” he’s been largely relegated to the status of a cult artist with a relatively small but extremely loyal core audience.

Jeffreys blends the multi-textured sound of his early albums with his later Rock-centric releases on The King of In Between, his first album of new material released in the U.S. in nearly 20 years. From the infectious Indie Rock ring of “Coney Island Winter,” the David Baerwald-meets-Curtis Mayfield noir Pop/Soul of “Streetwise” and the Blues thump of “’til John Lee Hooker Calls Me” to the Blues/Folk chug of “Love is Not a Cliché,” the Stonesy bluster of “Rock and Roll Music” and the Graham Parker-on-a-Reggae-buzz bounce of “The Beautiful Truth,” Jeffreys effortlessly blows through his style catalog and shows that he’s lost none of the power or the social consciousness that made him the critic’s darling in the ’70s and beyond.

It’s rare enough for an artist to conjure up an album with the kind of power and personality to be considered a career-defining work, but Jeffreys has done just that with The King of In Between, an astonishing 40 years after he made his equally strong debut.

Over the past 13 years, Gomez has been one of the most sonically and stylistically fearless bands in recent memory, from the shuffling Psych Blues of their 1998 debut, the Mercury Prize-winning Bring It On, to the Electronic Rock squall of In Our Gun to the brilliant hybridization of 2006’s How We Operate. In fact OperateA New Tide. could be viewed as the album where Gomez found their true sound, an absorbed amalgam of all the elements they had so flawlessly reflected over the first half of their career, a trend that was continued on 2009’s focused

Perhaps most ironically, the greater distance between Gomez’s five members, who once lived together and are now, in some cases, separated by oceans, the closer they become creatively. For their latest album, the appropriately titled Whatever’s On Your Mind, the quintet individually contributed nearly an album’s worth of material which was pared down to a mere 10 tracks, and the result is a brief and eclectic triumph. The Electronic pulse of “The Place and the People” is punctuated and hooked by masterfully strummed and swirlingly arranged R.E.M.-like acoustic and electric guitars, giving way to a frenetic U2-meets-Eno soundscape at the conclusion, while “Just As Lost As You” is a widescreen blending of British Folk and contemporary Rock that shivers with both great subtlety and intensity and the title track is a keyboard-and-strings evocation of the band’s early work.

Whatever’s On Your Mind relies on strings and horns more than any previous effort, and stands as further evidence of Gomez’s unique ability to remain astonishingly consistent while navigating an ever-shifting sonic course.

Fronted by the almost schizophrenically talented Katsuhiko Maeda, World’s End Girlfriend defies easy categorization. On WEG’s tenth studio album, Seven Idiots, Maeda creates a soundtrack that suggests Trans Siberian Orchestra on steroids and champagne, a Prog/Classical/Pop mash-up that is muscular and giddy and frenetic and undeniably fun. Maeda pinballs between genres and sounds with attention deficit speed but the shifts never seem capricious; “Ulysses Gazer” gives the impression of a radio dial being spun across a spectrum where Muse, Danny Elfman, Queen, Thomas Dolby, Radiohead, Testament, Raymond Scott and Mozart are all playing the same song on different stations in radically different styles but with the same visceral intensity.

Ignore the Emo-sounding band name; with Seven Idiots, Maeda makes cartoon music for intellectuals, Metal for eggheads, Classical for headbangers, Prog for 21st century schizoid adventurists, Jazz for geneticists, party vibes for blade runners. World’s End Girlfriend is everything on your iPod and more.