Over the past few years, America has seen dynamic changes when it comes to same-sex marriage. Federal court rulings have extended marriage equality to a majority of states, and now a series of cases to be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court involving Ohio and three other states could be the issue’s most definitive national moment.

Cincinnati is at the epicenter of that moment in more ways than one. The U.S. Sixth District Court of Appeals here set up the Supreme Court showdown by upholding Ohio’s 2004 constitutional amendment banning gay marriage, as well as similar bans in Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee. That flew in the face of a number of decisions by other federal circuit courts across the country, which have struck down the bans. Now the Supreme Court will have to mediate the disagreement.

Cincinnati also has a much more personal connection with the fight. Several of the plaintiffs whose cases will be heard by the Supreme Court live here. Despite residing in one of the final 13 states barring gay marriage, they say they feel welcomed and supported by their city. That’s a big change from just a decade ago, a change many hope will extend across the country.

Currently, 70 percent of the U.S. population lives in a state that allows gay marriage, according to U.S. Census data.

“I think for a lot of reasons, we have reason to be hopeful that history will be made next week,” says Cincinnati Vice Mayor David Mann of the upcoming court battle.

For the plaintiffs, the emotions are high, but the magnitude of the potential court decision that will bear their names and could affect millions is hard to fathom.

“It’s hard for me to emotionally grasp that,” says plaintiff Jim Obergefell. Because his particular suit against Ohio had the lowest case number, the case before the Supreme Court, Obergefell v. Hodges, bears his name. “On an intellectual level, I do a little, but it just doesn’t seem real.”

The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the cases April 28 and rule on the issue by the end of June. At stake: whether or not state bans on same-sex marriage violate couples’ civil rights, and whether states like Ohio must recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states.

Gay rights activists say issues with the bans are unconstitutional and compare the struggle for marriage equality with battles over civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s. Lawyers for states seeking to keep their bans, including Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine, argue that the matter is up to voters, not judges.

Repercussions for the bans go beyond a marriage ceremony, extending from birth to death. Ohio’s ban keeps the state from recognizing official documents like birth and death certificates on marriages performed in the 37 states where same-sex marriage is legal.

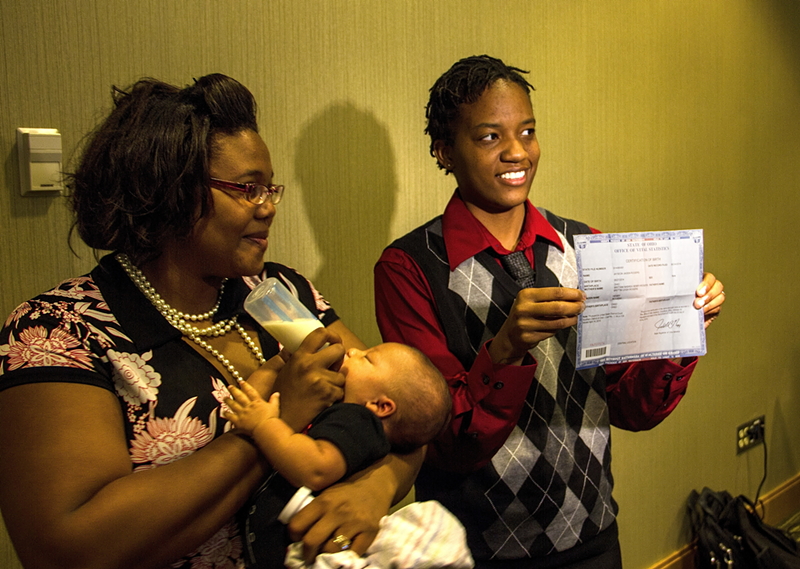

Plaintiffs Brittani Henry-Rogers and Brittni Rogers of Golf Manor met in 2008 and decided they’d like to start a family, so Henry-Rogers underwent artificial insemination to become pregnant. The two married in New York in January 2014. Their son, Jayseon, was born that June.

“Blood couldn’t make us any closer,” Rogers told CityBeat after the U.S. Sixth District Court of Appeals heard arguments about their case last July.

The Rogers won an April 2014 battle in federal court when U.S. District Judge Timothy Black ordered that the state allow both of their names to appear on Jayseon’s birth certificate. The state issued the certificate but appealed Black’s ruling. In a 2-1 ruling, the Sixth Circuit court in Cincinnati sided with the state.

If her name isn’t on Jayseon’s birth certificate, Brittni Rogers will have to go to great lengths to prove she has guardianship when signing him up for school, helping him get a driver’s license or traveling out of state with him.

“We just want to be treated as a family, because we are a family,” Henry-Rogers said. “We both take care of him, so we should both have the right to be on his birth certificate. Who wouldn’t want two moms?”

There are other challenges for same-sex couples seeking to be recognized by Ohio.

Jim Obergefell of Over-the-Rhine has become a national symbol for marriage equality thanks to his fight to be listed on his husband John Arthur’s death certificate.

Because Ohio forbade gay marriage, the two flew to Maryland, where same-sex marriage is legal, to wed in 2013 after two decades as partners. Arthur was terminally ill with Lou Gehrig’s disease and passed away a short time later. Obergefell successfully fought to be listed as spouse on Arthur’s death certificate, though Ohio appealed that decision and the Sixth Circuit also overturned it in its decision last August.

Though Ohio is fighting plaintiffs all the way to the highest court in the country, Cincinnati has staunchly supported them.

It’s another sign of the city’s continued evolution. Twenty-two years ago, Cincinnati passed Article XII, one of the most-restrictive anti-gay ordinances in the country. The charter amendment passed by City Council expressly forbade passage of laws protecting individuals from discrimination due to their LGBT status.

As Ohio was passing its anti-gay marriage amendment in 2004, Cincinnati was dismantling its anti-gay laws, revoking Article XII. Since then, the city has become increasingly LGBT friendly. In 2011, Cincinnati elected its first openly gay elected official, City Councilman Chris Seelbach.

Last year, the city scored a perfect 100 on the Human Rights Campaigns’ Municipal Equality Index. And in March, City Council passed a motion supporting same-sex marriage. Council has also recognized gay rights activists recently and has declared April 28 John Arthur Day in honor of Obergefell’s late spouse.

“We’re with you,” Cincinnati Vice Mayor David Mann said to Obergefell after council passed the motion recognizing Arthur. “We’re grateful for what you’ve done to bring things to this point. We look forward to taking steps to reverse some mistakes Ohio has made in the past.”

Obergefell still lives in the city he shared with Arthur since the 1980s. He says he feels nothing but support from Cincinnati.

“I really do feel like the city is behind us,” he says. “From the start, the city solicitor stood up in court and said, ‘We refuse to fight them on this.’ And the people in this city — I just feel a lot of love.” ©