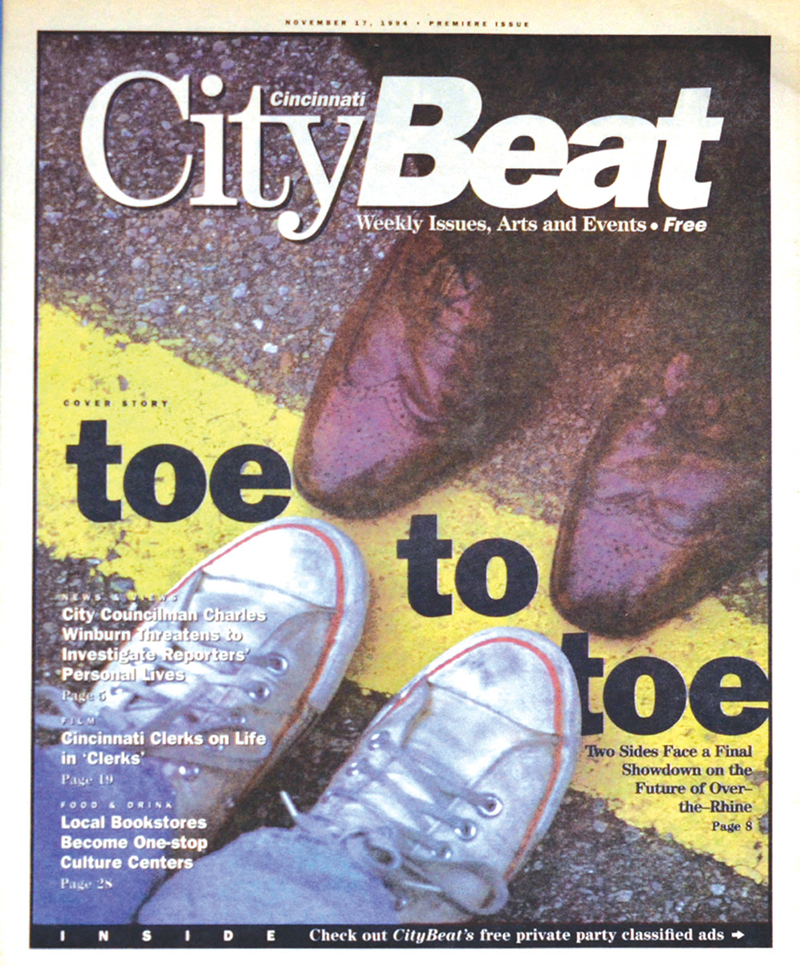

Ah, Volume 1, Issue 1, sporting that new newspaper smell. What better way to come out of the gate than covering the city’s most vexing problem: the decades-long decay of historic Over-the-Rhine and the lack of political will to do anything about it.

News Editor Nancy Firor’s cover story featured the subhed, “Two sides face a final showdown on the future of Over-the-Rhine” — a conflict that still resonates 20 years later. The story laid out the neighborhood’s sad decline and the stalemate between redevelopment advocates and low-income activists.

By 1990 Over-the-Rhine had 9,500 residents, down from 31,000 in 1950. More than $100 million in federal and city funds had been funneled into low-income housing there since the 1970 Housing and Urban Development Act. Just a month before CityBeat’s debut, City Council approved a $600,000 grant to open a housing and support center for alcohol and drug addicts on Vine Street, the neighborhood’s 15th shelter.

Buddy Gray led a vocal cadre of low-income advocates pushing the city to continue investing in services for the poor, the homeless and those struggling with substance abuse. He’d founded the Drop Inn Center, the city’s main homeless shelter, and ReSTOC, which acquired and developed properties as low-income housing.

ReSTOC owned 79 buildings and vacant lots in Over-the-Rhine by fall 1994, but more than half their buildings sat empty. Developers looking to add market-rate housing in OTR said Gray used the properties like “pieces on a chess board” to create anti-development “dead zones” across the neighborhood.

Multiple committees and studies over the prior decade had come to the same conclusion about the future of Over-the-Rhine: the only viable way for the neighborhood to cease being a ghetto was to invest in housing for all income levels, not just the poor. City Council found itself wedged between the classic arguments of “redevelopment” vs. “gentrification,” with no clear path forward.

Excerpt:

“Change starts, Jim Tarbell (then owner of Arnold’s Bar & Grill) suggests, by refusing to fund more low-income housing, shelters and the like. … There is plenty of room for all residents, rich or poor, he says, as long as they are willing to co-exist in a neighborhood that holds everyone — drug dealers included — responsible for their actions.

“There is not room, he says, for politicians who will not lead.”

Today:

Face it, most politicians won’t lead unless forced to. When the 2001 riots shut down most of the neighborhood (see “2001” on page 13), Over-the-Rhine was at rock bottom. Mayor Charlie Luken and the corporate community forged an emergency investment strategy that eventually led to the Cincinnati Center City Development Corp. (3CDC), and the OTR turnaround began.

Hundreds of other mileposts occurred along the way, including Gray’s tragic murder in 1996 by a mentally ill homeless man. Tarbell joined City Council in 1998 and served through 2007, championing the possibilities of Over-the-Rhine’s renaissance. Dozens of developers and individuals — Urban Sites, Model Group, Western & Southern and many others — have worked to rehab OTR’s huge stock of historic buildings.

But 3CDC’s work stands out as the linchpin for growth. The nonprofit group has invested more than $350 million in Over-the-Rhine, creating more than 500 units of market-rate and “affordable” housing; 30 stores and restaurants; 60,000 square feet of office space; and the new Washington Park. 3CDC owns another 100-plus vacant buildings that await redevelopment plans.

As streetcar construction continues (see “2009” on page 21), development likely will fill in more empty pockets in Over-the-Rhine, particularly north of Liberty Street.

Over-the-Rhine Community Housing, formed from ReSTOC, now manages more than 85 buildings in the neighborhood and last year placed 254 homeless people in permanent housing. The city’s Homeless to Homes initiative is designing new, larger, modern facilities for the Drop Inn Center, City Gospel Mission, YWCA and Anna Louise Inn.

Critics point out that each of those social service organizations — with 3CDC leading fundraising and construction — are moving out of downtown and Over-the-Rhine to adjacent areas, perhaps diminishing their ability to serve at-risk populations. The tradeoff for improved facilities, some argue, was getting out of the way of OTR’s redevelopment march.

Compared to 1994, Over-the-Rhine today is clearly different and undeniably better. Is it perfect? Of course not. But the way forward these days is being addressed face-to-face rather than toe-to-toe.