When we think about grand historical myths — things like the American Dream, Manifest Destiny or every war, for example — it’s important to acknowledge that society buys into these widespread accepted “truths” because of all the supporting evidence.

Art is often submitted as corroborating proof or validation of the truths we already tell ourselves as a civilization. But one cannot underestimate the sway that history’s author has upon the angle of the story and that is (perhaps unfortunately) altogether too often dictated by whoever is doing the storytelling: the winners.

In their exhibition Based on a True Story — curated by Steven Matijcio — Duke Riley and Frohawk Two Feathers proffer their own epic narratives. Wrestling historic imagery from the grips of hegemonic obsolescence, Riley and Frohawk weave them into a sprawling web of stories about a very different kind of protagonist — one who participates in civil yet rebellious patriotism.

And while many of the narrative threads that Riley and Frohawk propose might hold a kernel of truth, both artists approach their work from the perspective of people on the fringes of societies, both real and imagined.

Los Angeles-based artist Frohawk Two Feathers, the pseudonym of Umar Rashid, has been developing his “Frenglish Empire” storyline since 2006. His imaginary world enables Frohawk to retell the French Revolution as an alternate universe where France and England have joined ranks against the Dutch and other colonizers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

But because this is a retelling of history, Frengland is filled with tattooed people adorned in symbols of contemporary culture. For example, in a Frenglish North American Company advertisement titled “Son, it’s on!” (2013), the ostensible piece of Frenglish propaganda puts the call out for “able-bodied colonists” to take up arms against the Dutch.

The soldier of fortune in Frohawk’s painting leers at the viewer over his shoulder atop a rearing horse while wielding swords over his head. “Comply with us or Collide with us” — an appropriation of the maxim “Ride or Die” — is emblazoned on his saddle, and it is this clever critique of contemporary cultural clichés that is so provocative about the artist’s work.

Particularly with his portraits, Frohawk simultaneously satirizes and romanticizes historical painting. He treats his surfaces with tea and coffee to give them the look of a primary document — no doubt also a reference to the trade goods’ connections with colonial exploitation and their use as justification for empire building. His subjects are adorned in cultural signifiers of societal class and rank and, similar to the ways Romantic painters Goya or Géricault approached portraiture at various times in their careers, Frohawk’s noble social outliers look as regal as a Van Der Zee or Sidibé sitters and invoke our voyeuristic urge to look closely at those who are different — without cost to the subject’s dignity.

Boston-born, New York-based Duke Riley is likewise interested in historical obscurities. But while Frohawk seems to celebrate monarchical structures like the noble class, Riley is decidedly more populist in his approach.

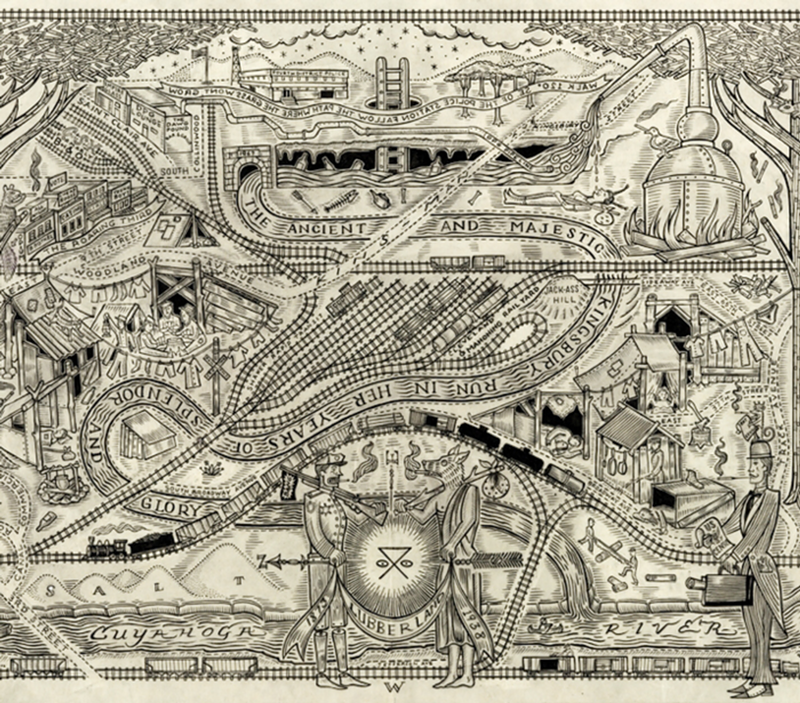

In his various projects focusing on outlier communities — “Reclaiming the Lost Kingdom of Laird,” Riley’s name for Petty’s Island, or “An Invitation to Lubberland,” about a Depression-era Cleveland riverside shantytown called Kingsbury Run — Riley employs installation, video, drawings and mosaics to recast the heroes and villains of historical dramas that happened in or near waterways.

Indeed, Riley seems frequently drawn to waterways, railways and other avenues of action as sites for his work, so it is no surprise that much of his imagery draws upon the visual language of maritime folk art. Appropriately enough, Riley’s day job is as a tattooist and his emphasis on craft involves a kind of implied performative action: illicit painting upon industrial gas storage tanks, the acquisition of materials from unauthorized expeditions to various historic sites.

Using found objects, like railroad spikes and nickels, Riley tells the story of a nomadic population and the implicit specter of their physical labor, which was crucial to the American economy.

As with all good history writing, the prospect of what we might glean from the past in order to shape the future looms heavy for the viewers of Based on a True Story. Luckily, talented artists with an interest in setting the story straight, like Riley and Frohawk Two Feathers, are looking back for us so that we might look forward to better times.

BASED ON A TRUE STORY runs though March 22 at the Contemporary Arts Center. More info: contemporaryartscenter.org.