Multiple factors have converged in Ohio to bring heroin addiction and overdose numbers to crisis levels, and law enforcement officials, doctors and politicians have all raised alarms about the growing problem during recent months.

But a near-concensus among experts that there exists a serious problem hasn’t resulted in an actionable plan to solve it. Clinics providing treatment options that can help addicts wean themselves off heroin are limited by a 14-year-old federal law restricting the number of people they can treat.

“We’ve got a problem when it’s easier for Americans to get heroin than it is for them to get treatment,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown during a July 30 conference call with reporters. Brown has cosponsored a bill in the Senate that would help lift the limits on doctors practicing at heroin addiction clinics.

The Recovery Enhancement for Addiction Treatment (TREAT) Act would increase the number of patients a doctor could treat in first year from 30 to 100 and allow doctors who undergo more training to apply to be able to see more patients after that first year. It would also allow nurses to prescribe the drugs if they complete special training.

Right now, there is no way to get a waiver to treat more than 100 patients in a year, and there are not enough physicians for the increasing number who need treatment.

There are several clinics in the region that can prescribe addiction treatment drugs, including one run by University of Cincinnati Physicians, Cincinnati’s VA hospital and the Central Community Health Board of Hamilton County, a clinic in Corryville supported by the County’s Mental Health and Recovery Services Board. Northern Kentucky has just one, the NKY Med Clinic. Each can serve a limited number of patients a year due to federal law.

The law, passed by Congress in 2000, limits physicians who treat heroin addicts to 30 patients their first year of practice and 100 every year after. The law was designed to limit the availability of methadone, another opiate used to help heroin addicts stair-step off the drug.

Methadone is easy to abuse, though, and requires daily doses to truly help treat addiction. New drugs like buprenorphine and naloxone are harder to abuse and easier to use, however. Many doctors and therapists have questioned the limits on clinics in light of these new treatment options and the state’s burgeoning need for care.

“If I have 30 more spots, or 100 more spots … whatever number I’m given, that’s what I’ll start working with,” says Mark Placentini, a doctor in Marion County, Ohio who treats heroin addicts. “If you don’t treat them, you won’t get the drugs out of the cities.”

Brown says the new law would save hospitals money by preventing overdoses and providing earlier fundamental treatment. Placentini says lifting the limitations on clinics could also have a ripple affect in the community.

“If there’s a home where there are five people on heroin in the home, and one of those people recovers and has work, that can influence the other people,” Placentini says.

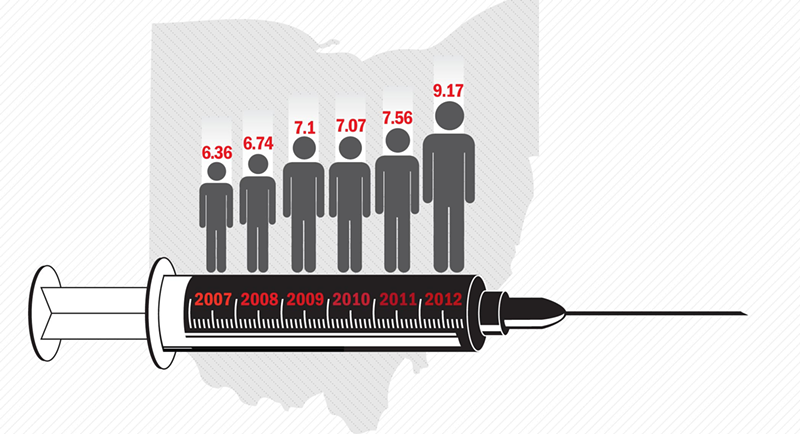

Drug overdoses have been the leading cause of accidental death in Ohio since 2007. Six-hundred-eighty people died from heroin overdoses in the state in 2012, up sharply from 426 the year before. Hamilton County has been hit hard by the rise in the drug’s popularity, seeing a big boost in demand for treatment. The county has the state’s highest rate of administration of naloxone, a drug used to treat addiction, according to data collected by the state.

Heroin overdoses are a big problem in Cincinnati. So far in 2014, EMS squads in the city have administered more than 1,000 doses of Narcan, an emergency drug used to treat overdoses, city records show. Overdoses have become so prevalent in the city that the Cincinnati Police Department is weighing equipping officers with doses of the anti-overdose treatment.

Placentini says heroin has been around for a long time in Ohio but notes that the numbers of people seeking treatment have jumped dramatically in the past few years. Placentini has joined Sen. Brown’s effort to increase the number of patients addiction clinics can treat.

The rise of heroin in Ohio comes as an unintended consequence of the state’s crackdown of other opiates, including prescription pills, addiction experts say. In the early 2000s, prescription opiates were widely prescribed, leading to a huge increase in abuse and addictions. They became so popular that illegal labs called pill mills began pumping out the synthetic narcotics to meet illicit demand.

Law enforcement in Ohio, led by the attorney general’s office, clamped down hard on the industry beginning in 2011, raiding and shutting down pill mills and others dealing the drugs. Prescription pill overdoses have dropped in Ohio for the first time since 2003, according to state data.

Although pills are harder to get now, many remain addicted to opiates. Meanwhile, heroin has gone from rarely-seen to nearly ubiquitous on the drug scene. And as supply has increased, the price has dropped. Addicts can often get a heroin fix for just $10 or $20, much less than more tightly controlled pills or other opiates.

Law enforcement officials say much of the supply is coming from Mexican drug cartels. After it crosses the border, heroin is usually shipped to distribution points like Atlanta and Chicago. From there, it comes to the Cincinnati area, often via I-71 and I-75. Once here, dealers cut it with other substances like powdered milk to increase its volume and make a higher profit. Sometimes, the drug is also spiked with other painkillers, making it more powerful — and more deadly.

The heroin trade is an international industry with a complicated supply chain. Its raw ingredients are extracted from milky opium found in the seed pods of the poppy plant, often grown in Afghanistan and countries in Southeast Asia. From there, it’s often refined by cartels in Mexico and Central America before shipment the United States.

The increased availability and low cost of the drug have led to a national emergency, law enforcement officials say. U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder has called the upswing “an urgent public health crisis” and called for action to curtail the drug’s availability.

Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine has used similar language here, calling the upswing an “epidemic.” DeWine created a $1 million anti-heroin taskforce in the AG’s office to help aid law enforcement officials in busting dealers. The crisis has a become a campaign issue, with DeWine’s challenger for AG, Democrat David Pepper, charging that DeWine hasn’t done enough to create treatment options for addicts or to stem the tide of heroin flowing into Ohio.

One of the first big landing places for the drug in Cincinnati is Northern Kentucky, where overdose and addiction rates are even higher than Hamilton County’s. In the Campbell County jail, half the 490 inmates housed in an average month are there for heroin charges. It’s not just low-income parts of Covington and Newport that are seeing overdoses and arrests, though. Law enforcement officials say they’re seeing the drug in more well-to-do areas like Fort Mitchell as well.

Law enforcement in both Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky say they’re working to cut off the supply of the drug, trying to bust dealers and traffickers who are bringing it into the region. Charges filed by law enforcement agencies in Northern Kentucky involving trafficking of the drug have gone from 400 cases in 2009 to more than 2,000 in 2013.

While law enforcement officials struggle with the supply end, others, including doctors and some politicians, have said that treating addicts and reducing demand for the drug is key. But as the need for addiction treatment services has skyrocketed, clinics have struggled to keep up.

The TREAT Act has received endorsements from doctors’ groups like the American Medical Association, the Society for Addiction Medicine and others, though some addiction experts warn it could increase abuse of methadone alternatives.

The bill, cosponsored by Brown and Sen. Edward Markey, D-Mass., was referred to the Senate’s Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions on July 23 and will need to be passed by that committee before moving on to a vote in the Senate. ©