T

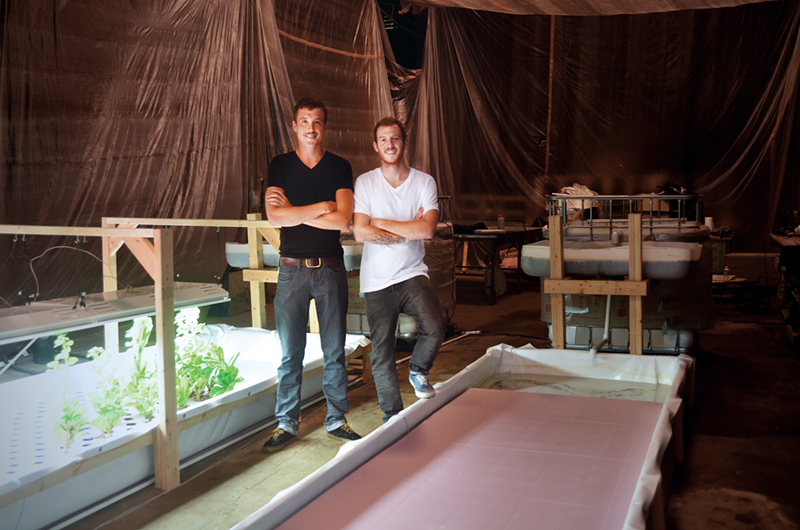

wo 23-year-olds growing plants in an Over-the-Rhine basement sounds like the beginnings of a Seth Rogen blockbuster, but housed in a six-story Apex warehouse on McMicken Avenue is the newest contribution to Cincinnati’s sustainable agriculture initiative.

One simply has to follow the sound of running water and the beats of Biggie Smalls down the stairs to the basement, where Kyle McGrath and Brad Ostendorf are hard at work cleaning, clearing, monitoring, growing and jamming. Their homemade aquaponics system, which combines hydroponics (growing plants) with aquaculture (farming fish), is steadily producing fresh food from nothing but two fish tanks, a few lights and recycled water.

Northern Kentucky natives and longtime close friends, McGrath and Ostendorf both graduated from the University of Kentucky College of Design in May 2012. Architecture degrees in hand, they turned to the restaurant industry for quick cash, but their odd jobs as bartenders and line cooks led to an interest in food, how it’s made, where it comes from and the notion that you can grow your own food rather than purchase it from a large supplier.

“With all the new OTR restaurants, there are so many chefs pushing for fresher menus,” Ostendorf explains. “The more we thought about it, the more it just clicked.”

URBTank, the name of the project and a nod to urban farming, strives to provide healthy, all-natural ingredients to local chefs, consumers and residents of the Cincinnati area without the added fertilizers and unsustainable conditions inherent in mass production. The system has been put into place in the heart of Cincinnati, residing in the basement of a former Christian Moerlein icehouse where the temperature is a cool and constant 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

The idea for an urban aquaponics system spawned from a capstone project the two friends put together during their senior year of college.

They tackled one big question and one big problem: How can we bring people back to the Ohio River? Working under the River Cities Project, the team explored Newport, Bellevue and Cincinnati, ultimately drafting a proposal for how to increase interest in the long-ignored riverfront.

“My particular group studied the Licking River,” McGrath says. “I came across this guy in Kentucky who was breeding these endangered clams. He had this weird hydroponic setup. We went with that idea of a place where we grow native fish and teach people about it while still populating the river. We pitched our idea, we pitched our design and then we graduated.”

Months later, in the midst of balancing part-time jobs, the team couldn’t shake the project from their minds and decided to pursue it as a true hobby. They built a small, 50-gallon system in a garage, worked by trial and error, and finally began to expand the project into a full-blown business endeavor. After contacting a former employer about a location, they signed the lease for their McMicken location in January of this year and have been cleaning and setting up ever since.

“We really haven’t had any help,” Ostendorf says. “It’s basically just us hanging out, listening to The Notorious B.I.G. really loudly.”

McGrath and Ostendorf are well aware of the challenges they confront trying to grow food in an urban environment, but they are even more focused on the benefits of their OTR location.

“Here in Cincinnati and OTR there are so many empty buildings,” McGrath explains. “We can come in here and we can grow 24/7, 365, and you can grow at a fairly large scale. This is still pretty small compared to a lot of commercial systems. We wanted to start small, get our bearings and figure out logistics first.”

Along with ability to grow in empty and abandoned buildings, McGrath and Ostendorf look forward to the collaboration projects that an urban environment provides. With so many businesses within such close proximity, the opportunity to work with chefs, artists, brewers and other producers increases enormously, and the team is striving to take full advantage of this setup. URBTank, the name for the operation which plays off the idea of a think tank, represents the movement to collaborate creatively with other locals and sustain a direct dialogue between urban farmers and consumers.

“We have sold some stuff to Taste of Belgium,” McGrath says. “And we have a good relationship with Ryan Santos, who’s been a really good help recommending us to chefs and getting our name out there.” Santos, who graced the cover of CityBeat in June, is known for producing pop-up dinners with local fresh ingredients in the Cincinnati area.

McGrath and Ostendorf hope to reverse the current dialogue between chefs and farmers that leaves chefs with fewer options and less specificity when it comes to their products.

Ostendorf explains: “The way they seem to work now is a farm grows so many things and that’s what they get to choose from. So they ask us what we have, and we’re trying to actually have a relationship where we grow for them, all year round. Ideally we’d want the chefs to say, ‘Hey, I want all of these things,’ and we would do it.”

In just a few months, McGrath and Ostendorf have already noticed the difference their system makes. Local chefs have shown interest in microgreens and microherbs, more delicate items that lend themselves to being grown in aquaponics conditions. Microgreens, the first true leaves of a sprouting seed in the earliest stages of growth, are popular among chefs for many reasons: They enhance the aesthetic of a dish, contain all the vitamins of a full grown vegetable in a compact form and provide immense flavor in a small package.

“Chefs can order microgreens from these large food providers coming from California,” McGrath explains, “but their choice is ‘microgreens’ and that’s it. What a lot of chefs can’t do much about is choosing which greens they get. That’s where we saw an opportunity to customize this for the chefs’ needs and wants.”

How does it all work? How do fish essentially produce the food we eat? It is a surprisingly simple process. It starts with two large fish tanks, which Ostendorf and McGrath plan to fill with local fish that work well in the temperature of the tanks. The fish produce waste that gets fed into a media bed of rocks, water and worms. When the water in the bed hits a certain level, it drains down into the plants like a filter. The plants then convert the ammonia from the fish waste into nitrites — toxic to fish — and then again into nitrates, which is very beneficial for the plants’ growth and safe for fish. The plants continue to grow and the water is recycled right back to the tanks, where the process restarts itself.

“Basically what we’re trying to recreate is a river system where plants and fish work symbiotically,” McGrath says. “The plants act as the trees or local fauna of the river system. Even though it looks pretty industrial we’re really just trying to get back to a natural state.”

One of the main benefits of aquaponics is its ability to sustain itself like a small ecosystem. Hydroponics (growing plants in water) lacks the nutrients that the fish provide, and therefore requires a lot of additives and upkeep. When hydroponics is paired with aquaculture (farming fish), the two systems feed off of each other to create a cycle that demands a relatively small amount of maintenance.

Ostendorf notes: “Basically all you do is feed your fish, keep an eye on your plants, and take them out when they’re ready. It really takes care of itself.”

Aquaponic techniques trace all the way back to ancient Rome, but the modern exploration of urban farming has occurred mostly within the past 20 years.

Becca Self, owner of FoodChain in Lexington, Ky., is working with the nearby West Sixth Brewing Company to make her newly installed aquaponics system a collaboration of businesses. Self and her team use the spent grains from the brewery’s mash

,

still 80-percent rich in energy content, to formulate food that she can feed to her fish. Therefore a byproduct that one would normally throw away helps sustain a system that produces fresh food for the community.

Word about URBTank has spread quickly, especially among chefs, and the team credits social media for playing a tremendous role in providing information about who they are and what they are doing.

“That’s how we got in touch with a lot of chefs,” McGrath says. “They will hit us up on Facebook or send us a tweet. It’s been really cool how quickly people attach themselves to it. You can see the gravity of what you’ve created just via Facebook.”

With Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and a number of chefs already on their side, McGrath and Ostendorf are confident about what URBTank can do for the Cincinnati area in years to come.

“I think (our goal) would be a sustainable business,” McGrath says. “Market ourselves, market the chefs, collaborate with other creatives, find a permanent house. We realize we’re not going to feed the community, but it’s just part of that network of small urban farmers trying to teach people that there are other ways to produce food. If you can do it in a basement like this, you can do it anywhere.” ©