Shhh! There’s a tree sleeping inside Phyllis Weston Gallery. You’ll want to be silent — not because you might awaken it, but so that it can awaken you to Shinji Turner-Yamamoto’s thinking.

Turner-Yamamoto is the Japanese-born artist who opened Cincinnati’s eyes to using Mount Adams’ crumbling, deconsecrated Holy Cross Church as an art venue. There, in 2010, he suspended a live birch above an upside-down dead one, roots intertwined. The peaceful “Hanging Garden” inspired thoughts about the connections among art, architecture, the environment, people, the spiritual and the secular. Doug and Mike Starn turned up the volume this fall by bringing to the site Gravity of Light, with its hissing arc lamp illuminating images from religion, science and nature.

Now Turner-Yamamoto’s Global Tree Project initiative quietly takes root at Weston’s gallery with De Rerum Natura: on the nature of things. The title references a first-century B.C. poem by the Roman Lucretius, who observed that “nature repairs one thing from another and allows nothing to be born without the aid of another’s death.” This insight led the artist to create “Sleeping Vishnu Tree” after seeing an uprooted oak. He envisioned a new universe emanating from the tree, like the cosmos formed out of a dream by the Hindu god Vishnu.

Though horizontal, the tree feels full of energy — like a fire, wave or dust storm. It was drawn on canvas with henna, chosen because the dye “smells like forest.” Turner-Yamamoto used a feather to create swirls in the powder and appreciates that I see not just a tree but wind. “I want people to feel the wind within them,” he says, and recognize their metaphysical connection to plant life.

The artist points out bluebell blossoms on the canvas. They grew near the tree. They’re now white, the color of the fine dust in his 2010 Contemporary Arts Center show Disappearances, which included plaster and paint chips from Holy Cross. “If you grind anything long enough, it becomes white,” he explained then. But from the white powder that exists just before something disappears, new objects will emerge, according to Lucretius.

A new universe needs stars, and gold leaf discs dot “Sleeping Vishnu Tree” and other works. Turner-Yamamoto didn’t know stars while growing up in polluted Osaka and was struck by his first views of constellation-filled skies. Now stars — convex, concave and burned-out circles — are one of his signatures. Even when stars are behind clouds, “it’s important to feel their presence,” he says. Continuing the Disappearances theme, he adds: “I want people to question why there are two kinds of stars in one painting. One may still be there (in the sky), but one may be really gone,” its dying light only now reaching Earth.

Turner-Yamamoto wishes for his art to feel ethereal like the heavens. Most works are gilded on the side with gold or silver. The metal reflects light, creating a halo and making the work appear to float. “I want the art to be physically there but have lightness,” he says. He turns off the gallery lights and we silently watch the white of a sun on acetate disappear. “Shadow is creating the work,” he says, humbling himself to nature’s artistry. He made the piece for a Japanese teahouse where a window was always open.

He explains, “I wanted people to feel the wind” with their eyes as the breeze rippled the thin acetate over a white panel.

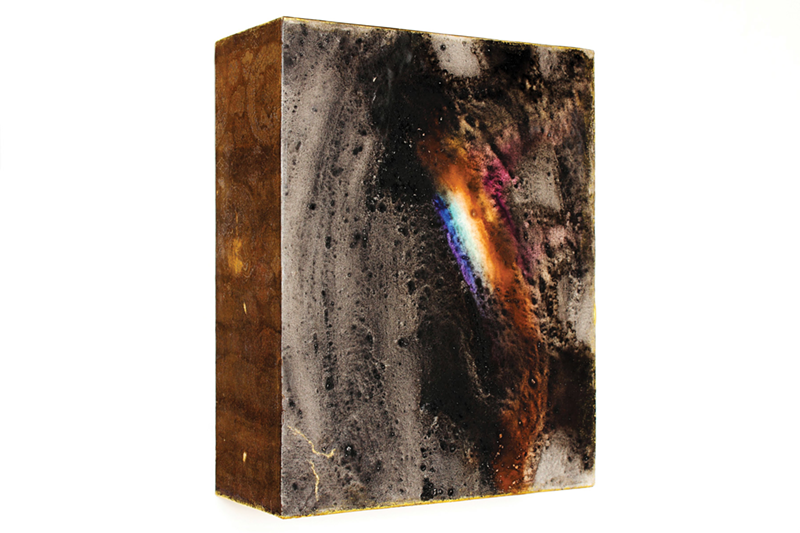

Interaction with nature happens not just before and after a work is created but during, too. Turner-Yamamoto, who now lives in Cincinnati and Washington, D.C., made his “Rainbow” and “Moonbow” paintings in Ireland, where there are “four seasons in a day.” To record the fickle weather, he covered papers with fireplace soot and peat ash, and then placed them outside so nature could have its turn. The splattered, layered works are reminders that we can’t have a brilliant rainbow without the rain – or art without effort. One moonbow includes a tuft of wool, a remnant from sheep that he discovered were eating some of the papers overnight.

“The purity of his materials (rainwater, egg, milk, beeswax) is refreshing,” says Morgan Cobb, an appraiser at the gallery. “The list of materials is more important than the titles,” adds Turner-Yamamoto. An “Irish Black Rainbow” scroll includes an Indian bead called a Krishna’s eye. Other pieces incorporate 19th century Japanese fabric.

“I like using the kimono, the eye, fragments of cultures,” Turner-Yamamoto says. This true citizen of the world then echoes Lucretius’ poem: “You never create out of nothing. You are helped along.”

DE RERUM NATURA: ON THE NATURE OF THINGS

is on display through Jan. 31 at Phyllis Weston Gallery (phylliswestongallery.com).