On a cold day last January, 38-year-old Scott Kehrer bought $200 worth of heroin from a Norwood dealer named Kenneth Gentry. Kehrer, an Arlington Heights resident and employee at Children’s Hospital Medical Center, had been struggling with addiction since a friend introduced him to the drug, which he had been getting from Gentry regularly.

Later that day, Kehrer was found unconscious from an overdose at a house in Lockland. He died soon afterward.

Kehrer’s death is one of many related to the region’s opiates crisis. In 2014, Ohio had the second-highest drug overdose rate in the country, with some 2,744 deaths — many related to heroin.

But it might have been another drug that actually took Kehrer’s life. The heroin Gentry sold him was cut with fentanyl, a prescription narcotic up to 100 times more powerful than morphine. It creates the same euphoria addicts crave from other opiates by driving up dopamine levels, creating a calming and addictive high. Authorities told a Hamilton County Courts judge that Kehrer had nine times the lethal dose of fentanyl in his system at the time of his death.

It wasn’t an isolated incident. Authorities are becoming increasingly concerned about fentanyl, which has its roots in the prescription opiate boom that sparked the ongoing drug crisis over the last decade. As that crisis has transitioned into the heroin addiction epidemic, fentanyl has made a comeback as a powerful additive.

“Fentanyl is often mixed with heroin, which is cheap, potent and available,” said Hamilton County Commissioner Dennis Deters, Chair of the Hamilton County Heroin Coalition. “Users are unaware that their drugs may have been cut with fentanyl or other adulterants, which places them at even greater risk of overdose or even death.”

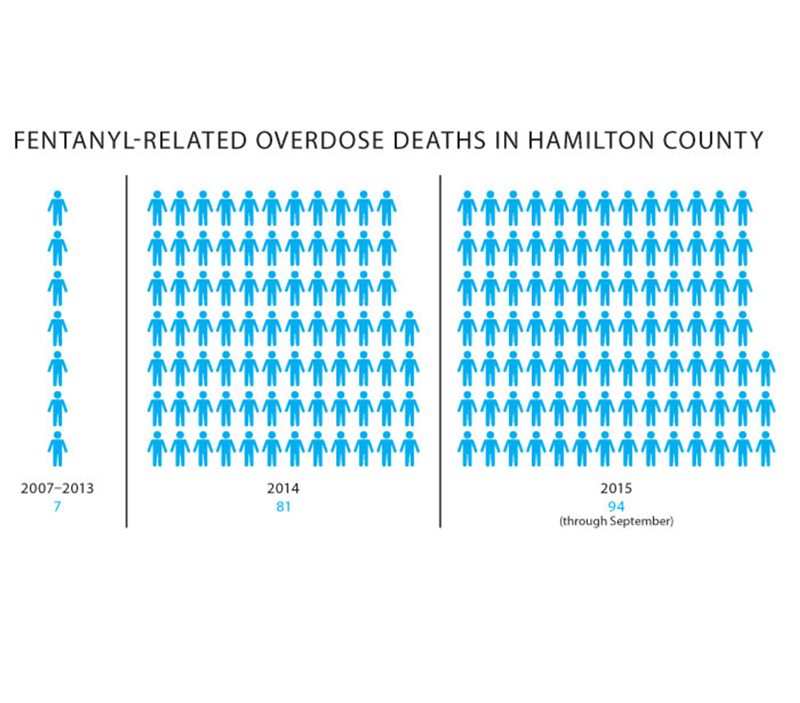

It’s a recent but quickly growing problem. From 2007 to 2013, according to Hamilton County Public Health, fentanyl contributed to just seven of the county’s overdose deaths. But in 2014, it played a role in 81 fatal overdoses, or 30 percent of the county’s 251 total overdose deaths.

Authorities are still analyzing data from last year, but the raw number of overdose deaths related to fentanyl was even higher in 2015 — 94 through September of that year. Last March alone, more than 20 people in Hamilton County died from fentanyl-related overdoses, according to a report by the county.

These deaths are often happening in specific corners of the county, including Norwood, Price Hill and the areas around Walnut Hills and Mount Auburn, perhaps a sign that certain dealers have latched onto the practice and have found a reliable source of the drug.

“As we saw increases in overdoses related to fentanyl, we took a hard look at various drug combinations, as well as a spatial analysis of deaths,” says Hamilton County Health Commissioner Tim Ingram. “There are a few pockets within the county that are experiencing much higher numbers of fentanyl-related overdoses.”

In many ways, the heroin and fentanyl crises have fueled each other to their current ghastly heights.

Prescription drug companies first developed fentanyl in the 1960s to treat severe pain associated with surgery and certain cancers. It acts fast, is very powerful and can be obtained in lozenge and patch forms. Like many powerful opiates, it’s prone to abuse.

Dr. Neil Capretto, who treats addiction at the Gateway Rehabilitation Center in Pennsylvania, told NPR earlier this year that problems with fentanyl started with medical professionals.

“Patterns of abuse actually began with hospital workers, anesthesiologists and nurses,” Capretto said. “There were a rash of (them) dying from overdose. You’d hear of them getting it in the operating rooms by drawing out fentanyl from vials and putting saline in its place.”

A powdered form of fentanyl, called China White on the streets, rose to prominence in the 1980s. With the advent of the drug’s patch and lozenge forms, patients who had been legitimately prescribed fentanyl began abusing more often as well. That dovetailed with an overall rise in prescription drug abuse that started in the 1990s and became a crisis in the last decade.

In the early 2000s, doctors began widely prescribing opiates like fentanyl, leading to a huge increase in abuse and addictions. The demand for those opiates was in large part driven by marketing pushes from major pharmaceutical companies, which funded academic studies, educational programs and medical groups like the Federation of State Medical Boards. Those organizations in turn endorsed increased use of opiates.

An article in the 2015 Annual Review of Public Health implicates the relationship between these companies and medical groups, and the role both played in pushing opiates.

“To overcome what they claimed to be ‘opiophobia,’ physician-spokespersons for opioid manufacturers published papers and gave lectures in which they claimed that the medical community had been confusing addiction with ‘physical dependence,’ ” the report says. “They described addiction as rare and completely distinct from so-called ‘physical dependence,’ which was said to be ‘clinically unimportant.’ They cited studies with serious methodological flaws to highlight the claim that the risk of addiction was less than 1 percent.”

One of those companies, Purdue Pharmaceuticals, paid $634 million in federal fines around those claims in 2007. Federal officials said the company learned in the mid-1990s that physicians weren’t prescribing opiates in non-cancer cases because they were worried about addiction, and then went about creating educational material and getting endorsements to assuage those fears.

Around the same time, medical professionals and federal officials were releasing a number of warnings about the dangers of opiates in general and fentanyl specifically.

But the damage was done. Prescription opiates, especially ones like OxyContin, became so popular that illegal labs known as pill mills began pumping out the synthetic narcotics to meet illicit demand. Law enforcement in Ohio, led by the attorney general’s office, clamped down hard on the industry beginning in 2011, raiding and shutting down pill mills and others dealing the drugs. Prescription pill overdose deaths then began dropping in the state.

The decrease in pill supply, however, led many to heroin. According to the federal government’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health, four out of five heroin addicts surveyed reported their addictions started with prescription opiates.

Today, heroin has gone from rarely seen to nearly ubiquitous on the drug scene. And as supply has increased, the price has dropped. Addicts can often get a heroin fix for just $10 or $20, much less than more tightly controlled pills or other opiates.

The heroin trade is an international industry with a complicated supply chain. Its raw ingredients are extracted from opium found in the seed pods of the poppy plant, often grown in Afghanistan and countries in Southeast Asia. From there, it’s often refined by cartels in Mexico and Central America.

Fentanyl, meanwhile, remains a popular prescription drug. In 2013 and 2014, doctors wrote more than 13 million prescriptions for the opiate, according to a March report by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Law enforcement officials say some fentanyl overdose deaths come from diversions of those legally produced drugs into the hands of drug dealers, who mix them with heroin or sell them straight, while others come from suspected illegal fentanyl labs.

It’s not the first time the combination has resulted in a rash of overdoses. In 2006, more than 1,000 people in Chicago, Detroit and Philadelphia died when batches of heroin containing fentanyl reached street-level dealers. The big bump in overdose deaths related to fentanyl has gotten the attention of federal authorities.

“Drug incidents and overdoses related to fentanyl are occurring at an alarming rate throughout the United States and represent a significant threat to public health and safety,” DEA Administrator Michele M. Leonhart said in a warning the agency issued this spring. The DEA raised alarms about the fact that the current outbreak is much more widely dispersed geographically than the one a decade ago.

That outbreak ended when authorities shuttered a single illicit lab in Mexico. But with the heroin crisis raging more intensely now, it might not be so easy to curb the narcotic this time. ©