T

he room is smaller than it ought to be. The terminal seats four dozen Amtrak passengers, a little more if you squeeze. And the trains come by only six times a week now: three late-night rides heading West to Chicago and three East to Penn Station in New York City. The Union Terminal (UT) is a flower that’s been plucked down to its last petals.

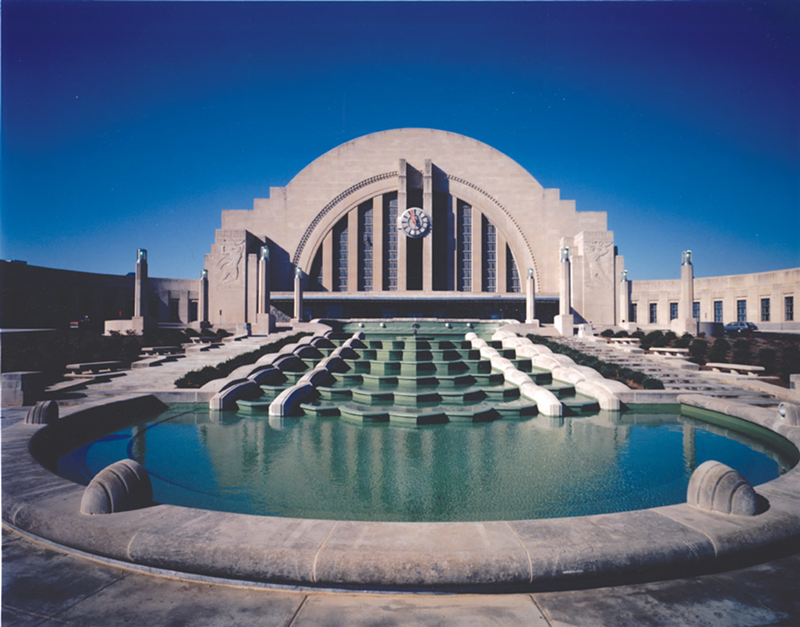

It didn’t used to be this way. The UT was once one of the nation’s grandest train stations and remains, arguably, the most beautiful. Looming tall in yesteryear’s Art Deco splendor, the UT was a transit wonder when it opened in 1933, offering dining, respite and art beneath the massive rotunda. In those days, the UT handled up to 216 passenger trains a day. Taxis and busses could drive beneath the dome to drop off rail passengers. There was a spacious, covered concourse for boarding outbound trains and hundreds of plush seats.

The UT was also built at a time when the era of rail hegemony was waning. Within six years of operation, local newspapers were already calling it a waste of money. Train traffic spiked during World War II and then declined slowly until Amtrak closed up shop in 1972. Passenger service didn’t return to the UT until 1991. Within those 19 years, the UT had its grand concourse demolished, served as a mall and flea market for a time and was saved from destruction by a 1986 bond levy that paid for its renovation and provided for the UT’s transformation into the Cincinnati Museum Center. That was 1990. And while the Museum Center has emerged as a major Cincinnati asset and as one of the central icons of our city’s identity, the passenger trains chug along sleepily in the background.

My family and I were sleepy, too, as we waited on the Cardinal’s arrival last month. We arrived around midnight in anticipation of boarding at quarter past one, but the train didn’t arrive until well past 2 a.m. We were told that a drunk had blocked the tracks and that, while he escaped injury, it took some time to check out the train and ensure that it was still safe to drive after the collision.

My wife and I and our two little children made the best of the hard plastic chairs and smooth marble floors. It made me long for the comparatively soft seats at an airline terminal. But this was our great Western odyssey and it was bound to have some hiccups.

We rode the Cardinal for nine hours until we reached Chicago’s Union Station. There, we transferred to the California Zephyr, which took 52 hours to deliver us to San Francisco. After six days in the city of St. Frank, we headed down the coast on the Pacific Surfliner to Los Angeles and then we returned on the Southwest Chief to Chicago — a tight, 43-hour trip. Finally, we took the Cardinal back home to Cincinnati. Six days of travel for six days in California. You’d better believe that getting there is half the fun if you’re making such a trip.

Stepping into the experience of an anachronistic vacation is as amazing as it is difficult, simultaneously the intimate family togetherness we sought and a too-close-for-comfort scenario that left little time for relaxation. With the UT’s concourse gone, riders board the old fashioned way: outside from a platform. And you wait, with your carry-on luggage in tow until you hear, “All aboard!” They really say this, though it’s tough to hear over the engine. We listened for the train’s whistle. Once it blows, you have about a minute to get in. It will leave without you if you haven’t boarded.

There are stops every hour to three hours. We got out every chance we could to stretch our legs. Drunks on the tracks aside, the train is usually on time. I was able to nail our stop in Ottumwa to within five minutes and had a pizza delivered to the train. Making games like this while riding through unremarkable stretches of land helps pass the time.

Of course, when the train cuts into Colorado, there’s much outside the windows to keep your attention during the long days. The windows at our seats were large and panoramic. Even coach seats are like little recliners and offer four feet of room between one headrest and the next. And the views are jaw-dropping: mountains and prairies, desert and rivers. We passed through Denver, Salt Lake City, Reno, Nev. and Sacramento, Calif. The terrain was otherworldly and remote, places unseen from car windows because roads don’t go there.

There’s drama, too. Outside of Denver the Zephyr hit a cow carcass. The cow had been killed by another train and its body had been thrown onto our tracks. Driving over it damaged the brake lines. Two repair stops were needed to keep us safe on our trek through the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The return trip offered the staggering beauty of coastal California, the flat, red rocks of New Mexico and the wide, blue Southwestern skies. The trains also brought us through the backyards of some very poor communities. There, thousands of people live in remote areas in worn out shacks with little resources. Knowing this and seeing this are two different things.

Rail trips are sobering in this way and accommodations — both coach and first class — that seem spacious in daylight can feel like hard little boxes at night. There’s a curious mix of comfort and discomfort that comes along for the ride. And the slow nature of the trip helped us see things — each other and our nation — that we might otherwise have missed. “Blink and you’ll miss it” comes to mind when I think about how I normally experience life versus how it feels when it’s slowed by the rails. “Blink and you’ll miss it” could also be true of passenger rail itself.

An Amtrak conductor, who asked that I not use his name, told me the train I was on was 40 years old.

“It’s been refurbished and refurbished and it will be refurbished again,” he said. “There will never be new trains and there will never be high-speed rail in this country, not in our lifetimes. Amtrak has never turned a profit. Not once in 40 years.”

He said he worries about discussions within Amtrak of privatizing Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor trains, the only rail segment that earns enough to be privatized.

“If that happens,” he said. “Cross-country trips like this will be gone.”

Book a ride from UNION TERMINAL on the Cardinal at amtrak.com.