Jay Porter is the founder of the now-defunct The Linkery, a farm-to-table restaurant in San Diego, and recent posts on his blog, jayporter.com, have caused a stir in the dining world. The posts were follow-ups to a New York Times article on The Linkery’s decision to be a tip-free restaurant with fixed service charges, divided among servers and kitchen staff, added to every check. According to Porter, eliminating the standard form of tipping made The Linkery a better restaurant. In his experience, it empowered the servers, brought the kitchen staff’s earnings closer to those of the wait staff and helped the employees become a better team. It also took some of the “power imbalance” — as Porter calls it — out of the diner/server relationship.

But the question is, if diners don’t tip, won’t the quality of service go down? Not according to a 2003 study by Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration. Their research indicated that average tip percentages are only “weakly related” to service quality — by less than two percent.

But local server Suzy Nagy of Nicola’s and Please disagrees. “I think that a system like [Porter’s] would only work in certain kinds of restaurants,” Nagy says. “In higher-end restaurants where food is what brings the guests in but wine sales is where the actual money is and overall experience is crucial, you require a very knowledgeable service staff who is also very technically proficient. If an entire city banned tipping, it might work. But in a city where you’re the only one doing it, the best and most knowledgeable service staff is going to go where they can make the most money.”

Why do we need to tip, anyway? According to the Department of Labor, wages for tipped employees in Ohio restaurants with gross sales less than $255,000 can be as low as $2.93 an hour plus tips. If the restaurant has gross sales higher than $255,000, wages skyrocket to $3.50.

Essentially, the tipping customer is playing the role of the employer — paying the workers the remainder of their wage.

Between Porter’s posts, the Times article and resulting Facebook posts, along with recent headlines on a local lawsuit regarding tip sharing at Jeff Ruby’s, people are talking about this complicated and sometimes taboo topic.

Three former employees of local restaurateur Jeff Ruby are claiming that they were forced to share their tips with kitchen staff and restaurant managers, which lowered their wages below minimum wage. Ruby refutes their claim, stating that his servers earn, on average, $65,000 per year and have 100 percent company-paid health insurance coverage.

Basic tip-sharing is common. When I waited tables, at the end of each shift, the servers voluntarily tipped the bartenders and bus people who had helped us through the night. Voluntarily — that’s the key. By law, in Ohio you are allowed to keep all of your tips if you earn less than minimum wage.

In California, the law is a little less restrictive. When Porter banned tipping at The Linkery, he added a service charge that allowed him to redirect about a quarter of that money to the kitchen staff.

Julie Francis, chef and owner of Nectar in Mount Lookout, works to improve teamwork at her restaurant through tip-sharing and a tip-out system, where the wait staff shares tips with the support staff.

“I really took this issue for granted before reading [Porter’s blog],” Francis says. “But I have always known that injustices can happen daily with the tipping system to the customer and server, and the inequality of pay between front and back of the house has always bothered me.”

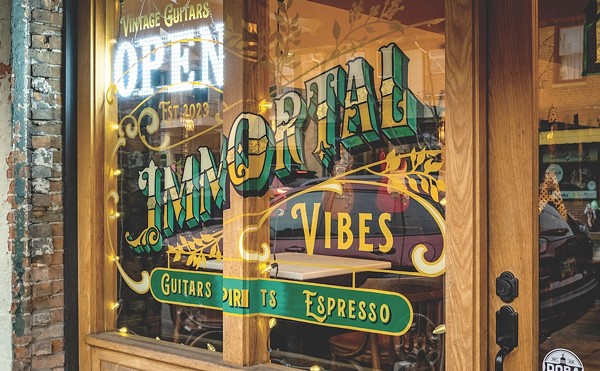

Chef Jose Salazar, who opens his new namesake restaurant Salazar in Over-the-Rhine this fall, appreciated Porter’s motivation but thinks the experiment could never happen in Ohio.

“I wish Ohio’s laws would change to allow tips to be dispersed evenly,” Salazar says. “But I think it would be difficult to implement change at the city or state level. I’d like to see the federal government step in and make the laws the same for all states.”

“It’s a very complicated issue,” he continues. “For me, the bottom line is how can we, the industry, find a way to raise the wages for cooks and dishwashers. The fact of the matter is profit margins are very low despite what some consumers might think. On one hand, we know workers deserve more — a lot more. On the other hand, there wouldn’t be jobs to go to if we paid the higher wages that we’d like to. The tip sharing system would help balance the scales, but I can’t help but think how many servers would be opposed to giving up a portion of their money. We’d be in for a fight.”

CONTACT ANNE MITCHELL: [email protected]