Great movies allow their main characters to live their own lives, to be set free from the kind of rigid determinism that all too often comes from too-carefully plotted screenplays or too-conventional audience expectations.

By those standards, as well as many others, director Robert Kramer’s Route One/USA — which begins streaming Friday Aug. 28 at Cincinnati World Cinema’s website and continues through Sept. 30 — is a great movie.

First released in 1989 but little seen then, Route One has been restored and digitized by Icarus Films and is getting a national release. Because it is 4 hours long, it streams in two parts. In The New York Times last week, critic J. Hoberman said that the film feels so timely “most of it could have been filmed last year.”

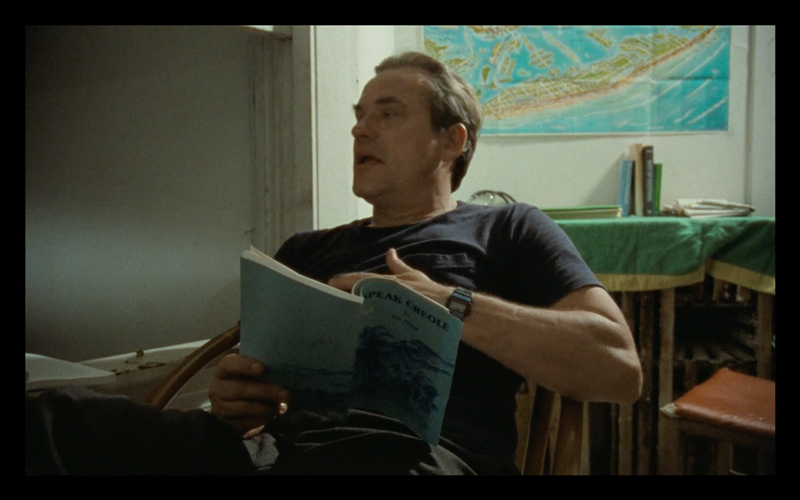

It features the actor Paul McIsaac as Doc, a 1960s political radical who became a physician and is now returning to this country after working in Africa. He comes back for a road trip with an old friend, director Kramer, to see how the country has changed — or hasn’t — during his absence. Doc is looking for a place to be an altruistic doctor as well as a decent person. He is friendly, sometimes hopeful, but also deeply introspective and, in general, constantly searching. He consistently takes actions that catch us — and the movie — by surprise.

In Boston, Doc visits a neighborhood Portuguese food market/gift shop, winding up drinking wine with the owner sitting among the wooden kegs. “I think you’ve built a good life in America,” Doc says, before ruefully confessing that his own father — a Scottish immigrant — did less well. In a grim Bridgeport, Connecticut, which looks like a city bypassed by progress, Doc fidgets at a free but formalized Thanksgiving dinner for the needy, then goes outside and meets a man who offers booze from an apple juice glass. The man, somewhat worse for wear, proudly says he put his kids through college. In Fayetteville, North Carolina, he visits a frail middle-aged newspaper reporter, Pat Reese, who tells him he was shot in the mouth by a man he was investigating. Doc hugs him.

What is especially surprising is that Route One/USA is a documentary. Despite the presence of the fictional Doc, most of the people he meets are exactly who they say they are. (There are a few recognizable public figures, like Jesse Jackson and Pat Robertson.) Critic Hoberman compared it to Robert Frank’s classic 1950s photography series, The Americans, for its ability to non-judgmentally allow its subjects to reveal themselves, as well as the nation they live in, for better or worse. That makes the presence of the fictional character Doc a great risk, but it works triumphantly. Rather than being nostalgic, it comes across as relevant — urgent, even — today.

“Looking at Route One, I have to look at it not only in the context of what we did when we did it, but where we are today,” says McIsaac, in a phone interview from Long Island. “I’ve lost none of my enthusiasm for our political and moral commitments of that time as I see it again.”

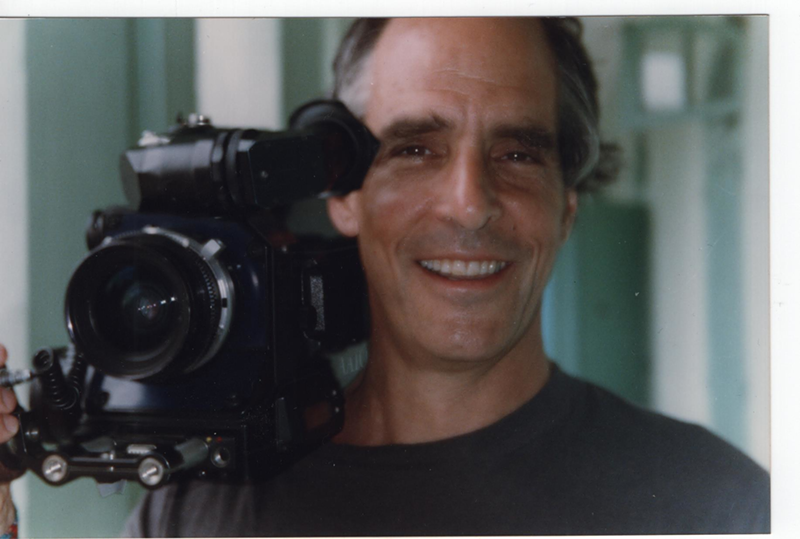

Kramer, who died in 1999, himself was a 1960s radical who had left his country to be able to keep making films abroad. He envisioned Route One/USA as a chronicle of his homeland return after a decade in France. He and a small crew would take a long road trip from Maine to Key West along U.S. Route 1, which had been the primary route along the East Coast before modern expressways.

Kramer was the son of a doctor who entered Hiroshima shortly after the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb there during World War II. Kramer helped found Newsreel Films, a collective of politically active filmmakers out to document protest/resistance during a time of freedom/anti-racism struggles and opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam. He also moved into still-political but more personal projects, like 1970’s Ice, a drama about American leftists actually staging a revolution, and 1975’s Milestones, a poetic film about trying to adapt to changing times.

McIsaac, himself a political and cultural activist, met Kramer at Newsreel Films meetings, and was cast in Ice as one of the revolutionaries who survives the crackdown. He also had a background in acting, including improvisation. After losing touch, the two rekindled their friendship at a 1984 reunion of Free Vermont, a collective of activists — including Newsreel Films veterans — who had settled in that state. (An affiliated organization, the Liberty Union Party, started Bernie Sanders’ political career.) At the time, McIsaac was a radio documentarian making “Reunion of Radicals” for National Public Radio.

Because they both still were working in media and the creative arts, their talk turned to working together. They discussed the idea of a character who felt the 1960s revolution and turned to medicine to help others. (Doc was somewhat based on Weather Underground member Alan Berkman, who survived a jail term and as a physician dedicated himself to helping AIDs patients.) So they made 1988’s Portugal-set Doc’s Kingdom, about a physician fighting burnout.

For Route One/USA, Kramer wanted to apply his skills, and his political sensibility, to a documentary focused on his own American discoveries. He had a tiny crew and at first wanted McIsaac to serve as a kind of location scout.

“One of the things I knew to do (as a journalist) was to go into town and figure out who is the most interesting person to talk to,” McIsaac says. “(Kramer) said, ‘Why don’t you do that? We’ll have a little money for it, and see what you find.’ So, I got on the road and started doing that. Now this is me — there was no discussion of Doc at all. And as we did that...we realized I wasn’t just finding people, but Doc was sort of pressing himself into it.”

The result is that Doc’s character explores his own past as well as that of the country he left. In Concord, Massachusetts he visits the meeting hall where Henry David Thoreau spoke out in support of abolitionist John Brown, who had raided a federal armory in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia to seize weapons and arm slaves for a rebellion. Brown was executed for his act. Doc reads the speech from the stage, breathing heavily from the strain when finished. (Kramer then moves to the next scene, a bitterly ironic factory that makes the red plastic houses and play money for the capitalistic Monopoly game.)

McIsaac says that Kramer’s crew had misgivings about his desire to play Doc in the film, since Route One/USA was to be about encounters with real people. This change meant those people would still talk about themselves, but now to an actor playing a role rather than to a documentarian asking questions.

“They said people are not going to talk to a fictional character,” McIsaac recalls. “I said I don’t agree, this is America and people are completely mediated. I was right. I can’t remember a single person who said, ‘Get out of my face’ or who didn’t get it. They immediately played their role. People know what it is to play themselves.”

The scene that still amazes McIsaac comes in Brooklyn, where Doc has a job interview with physicians helping AIDS patients at a beleaguered city hospital. One asks him how he could last for 10 years working in Africa and not be exhausted by the demands; he answers that “the idea of revolution pushed me for a time, then alcohol, some drugs.” One of the interviewers warns him, “You’re not going to get any kudos here. Nobody is going to go ooh and aah when you say what you’re doing. It’s a slow war on people, slow war on us.”

They knew Doc was a fictional character being played by McIsaac, but it didn’t matter. “They were expressing themselves and saying just what they’d say to (a real) Doc, and they just totally got it,” McIsaac says. “They knew their role at that moment is as a doctor who works at an AIDS center talking to a doctor who worked in Africa and is looking for a place to work.”

Apart from the narrative, which can reveal itself in short, sharp segments that don’t always provide context, director Kramer’s movie is consistently visually arresting — beautiful in its dedication to both straightforward and artful abstractions. He puts together quietly moving montages, like one of the foggy, doomy landscape around New Hampshire’s Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant that conjures ghosts of Chernobyl. Or he can focus underwater to portray a coral reef within an ethereal green dreamscape. The film also lets him explore some of his own interests without McIsaac: talking to refugees; visiting the grotesque Medieval Torture Museum in Saint Augustine, Florida. The film also has a beautifully spare musical score.

Route One/USA’s greatest surprise comes when Doc, in Georgia, decides to leave Kramer and crew. McIsaac made that decision because he felt it was what Doc should do in the moment. He then goes off to Miami and puts together a fictional life for Doc — a home, a girlfriend, a job working with Haitian refugees — that Kramer filmed as real because he acknowledged it made sense for Doc. It’s tricky stuff — post-modernist, maybe, or Brechtian in the way this portion of the film risks calling attention to its theatrical artificiality. Except it plays as true because Doc consistently seems so honest and open a character, and is so well integrated into the American landscape of the time.

“As I look back on it, I think that was honest,” McIsaac says. “He wants a job that’s meaningful, wants a person to love, a place to be. He doesn’t want to keep drifting with Robert in his abstract cinematic world. I like the fact we can let Doc be just a person. That is another revelation for me — if you’re honest to who this character has become, you can’t impose your own values or desires on them. You have to let them be who they are.”

McIsaac has said in the past that Route One/USA, Doc’s Kingdom and Ice shape him as a kind of Odysseus trying to come home from the wars. That’s true, but the sorrows he finds in America — environmental concerns, racism’s legacy, violence, stressed health professionals, struggling immigrants, decaying cities, a nascent religious right, a press under attack — also make this film effective as a report from America today. And Doc serves as an inspiration for change.

“It’s very exciting to try to help and be part of movements today, based on what we did back then,” McIsaac says. “That’s very dynamic and very exciting, not as nostalgia but as a feeling that one’s life has continuity.”

Route One/USA streams in two 125-minute parts starting Aug. 27 and running through Sept. 30. Rental fee is $10 per household and there is a one-week streaming window. For tickets and more info, visit cincyworldcinema.org.