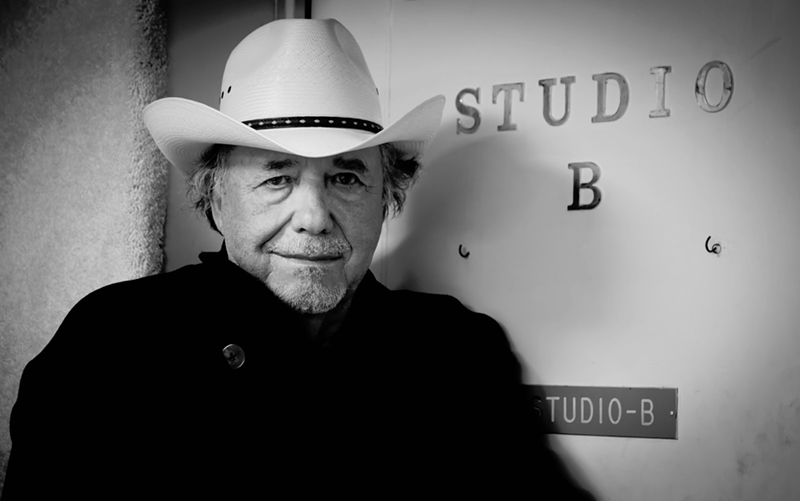

Last October, Bobby Bare was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. His long career featured some twists and turns that found him leaving his southern Ohio home to try and find success in California and elsewhere before eventually landing in Nashville. Along the way, Cincinnati’s Fraternity Records played an unexpected part in his success.

Once Bare arrived in Nashville in the ’60s, he established himself as a Country music recording and TV star. As time went by, he would become one of the fathers of the Outlaw Country movement, the early ’70s anti-Nashville scene that spawned edgy, dope-smoking artists like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver.

But long before that, Bare grew up in in a small town just north of Ironton (near the southern-most tip of Ohio) with a father who was a farmer and coal miner. He soon discovered a love for music and began to play clubs as a young man, but an unforeseen set of circumstances led him to head west. It all started when Bare was singing in a bar in the Ohio River town of Portsmouth in the early ’50s.

“I knew I was going somewhere,” Bare says about his musical dreams as a young man. “It was December in southern Ohio and at this particular time I was in Portsmouth. Me and my little band were playing at the Stone’s Grill..

“This guy showed up with a Nudie suit on,” Bare says, referring to the rhinestone-laden suits made by tailor Nudie Cohn and worn by many Country and Rock artists, “and an old convertible with a plastic rear window. He was going to California and wanted to know if any of us guys wanted to go with him. I said, ‘Hell, I’ll go!’ My bass player couldn’t, because he had a wife and kids. But my steel guitar player says, ‘Yeah, I’ll go.’ So, the three of us took off.”

As with most tales like this, there was more to the story. The stranger was not taking them to California out of the goodness of his heart.

“The reason he wanted us to go is because he didn’t have gas money to get back to California,” Bare says, laughing. “The thing of it is, by the time my steel guitar player paid his bar bill, he didn’t have any money either. It turned out that I was the only one who had any money and I only had about 40 bucks. But he did introduce me to Speedy West, the steel guitar player. Speedy loved what I did and … and eventually Speedy got me a record deal with Capitol Records.”

Bare recorded some Rock & Roll sides for Capitol, but the records didn’t make much impact. Then fate chimed in. Bare returned to Ohio in the late ’50s to prepare to go into the Army. Just before he did, he recorded a demo of the song “The All American Boy” for a friend named Bill Parsons. Cincinnati’s Fraternity Records bought the demo, released it as a single and it unexpectedly climbed to No. 2 on the Billboard singles chart. But it wasn’t Bobby Bare’s first hit. While he did the singing on the record, the label credited the single to Parsons.

Bare had just started his military stint when the song started shooting up the charts.

“I remember hearing ‘The All American Boy’ played on the radio about a week after I cut it there in Cincinnati,” Bare says. “I was in the Army. I was in basic training at Fort Knox and somebody had a transistor radio and was tuned in to WLAC listening to (DJ) John R and he played ‘The All American Boy.’ I didn’t even know it was out. I had never heard of the record company in Cincinnati that wound up with it. But, I told the guys, ‘Hey, that’s me!’ They said, ‘Oh shit, Bare. Shut up. We got to get up and fall out at 5 o’clock in the morning. Go to bed. You’re dreaming.’”

After Bare left the army in the early ’60s, he returned to Cincinnati to continue making records for Fraternity … under his own name.

“I wound up recording for that label and becoming really close friends with Harry Carlson, who owned Fraternity Records,” Bare says. “I became really close friends with him and his wife until they died. After they retired, they moved to Fort Lauderdale the last six or seven years of their life, and I went down for their funerals.”

In 1962, RCA Records signed Bare and he moved to Nashville. But during his brief stint on Fraternity, Bare did sessions at the studios of the legendary King Records.

“I did quite a bit of recording over there at King Records, at the old King studios that they had on Brewster Avenue,” Bare says. “That’s where James Brown did all of his hits. Syd Nathan was a big, old boisterous guy. He didn’t beat around the bush. He was a package.”

Once Bare signed to RCA, things really took off for the future hall of famer. His songs “Detroit City,” “500 Miles Away From Home,” “Four Strong Winds” and “How I Got To Memphis” ignited a two-decade period of hits and the rest, as they say, is — literally — Country music history.