S

wans, frontman Michael Gira’s long-running musical outfit founded in the midst of New York City’s early-’80s No Wave scene, seems to be in a good place these days. And for a band notorious for its creative tensions and ever-shifting lineups, that’s saying something.

After more than a dozen years of inactivity, Gira reconvened Swans — now a sextet that includes longtime guitarist Norman Westberg — in 2010, dropping the well-received studio album My Father Will Guide Me up a Rope to the Sky by year’s end via Young God Records, which has put out everything Gira’s done since he founded the indie label 23 years ago. Extensive touring followed, culminating in 2012’s special-edition double live album We Rose from Your Bed with the Sun in Our Head, the proceeds from which would help fund the band’s next studio effort.

That next effort, released just a few months later, was The Seer, a dense monolith of a record that is as compelling as anything Swans has released in its knotty three-decade history. The 32-minute title track is the obvious centerpiece, an epic, ebb-and-flow soundscape that employs almost everything the band has ever tried: moody, dissonant guitar noise; freaked-out Folk; percussive gymnastics that seem borne of Jazz-like improvisation; blissed-out drones that can be both menacing and ethereal; spare, spooky vocals in which Gira repeatedly monotones, “I see it all”; and much more than can reasonably be listed here.

Gira, speaking to CityBeat via an appropriately fuzzy cellphone connection from his home in upstate New York, was less contentious in conversation than his reputation would suggest. (He even laughed a couple times.)

CityBeat:

I read on your Facebook page that you guys are going to release another live record before starting the next studio project. What was the thinking behind that decision?

Michael Gira

:I like the idea of every time we finish, like, a year of touring, doing a live album. It’s kind of a marker in time of where we were during that period. It’s for fans and people who were already interested (in us), basically. And it also — since I do these things special-edition and handmade — raises money for the rather daunting expenses of making the studio album.

CB:

Looking at clips of your recent touring on YouTube, it’s interesting that you essentially seem to be writing new songs in front of the audience. Do you find that daunting?

MG

:Yeah, we’re doing it in front of the audience. “The Seer” started out just as a groove (during the live shows); it was different than it ended up on the record. We just kind of took it where it went and gradually it metastasized into what it became on the record. It’s like 30 minutes long or something on the record. It’s a challenge, you know. It’s not like we get up on stage and have no idea what we’re going to play, but it keeps things sort of on the edge of failure, which is a nice place to be, I think, because you have to fight to make something happen. I don’t really want to recite or replicate songs from a record; that just doesn’t interest me anymore. I’d rather be making something happen in real time.

CB:

How have audiences responded to that?

MG

:The shows are filled pretty much with people that want what we have to offer. They’re not coming to see the recent record. They know it’s going to be a pretty intense experience and they come for that.

In that way, it’s not something they just read about in the press; it’s people who genuinely see that they have an affinity for what we’re doing. It’s incredibly encouraging to see so many young people. In smaller towns it seems to be the older guys in black T-shirts (laughs), but in more urbane places it’s thankfully a lot of young ladies, as well, which makes guys like us feel a little bit vital.

CB:

You seem like you have a very specific vision in your head, but you also seem like you’re open to discovery. Does your band find that dichotomy tough to deal with?

MG

:(Laughs) Therein lies the hell in being in my band. I drive my musicians crazy with that, but it’s a constant process of discovery, really. We’re all trying to find the sound. We’re really an ensemble; it’s not like six players just playing their parts. When it’s really working, we are completely subsumed in a sound that’s bigger than us. It’s just kind of trying to find a way where that can happen.

CB:

I thought it was interesting and apt when you said you were the John Cassavetes of Rock (Cassavetes was an indie filmmaker whose pre-shooting script was ultimately altered via nurtured improvisation with his actors).

MG

:I guess I have a sensibility or an aesthetic or a vision or something in that I’m most open to random events. In fact, I like random events. I like surprises — I then can incorporate them into the general flow of what’s going on. When I go in the studio I usually make these charts and I map everything out, and then after a week in the studio I just throw the fucking thing away because it doesn’t make sense anymore because things have changed so much. It’s just a matter of accepting accidents and chance and let that guide the thing sometimes.

CB:

How do you know when a song is done?

MG

:Anymore it never is. It’s just not done. It’s never done. We tweak it and edit it and the other things one does in the studio, and then if we play that song live, it changes again. Some songs start out on acoustic guitar and that’s a completely different version of it, and by the time it goes through the recording process and the touring process it’s a completely different beast. Eventually its blood has been rung dry and then it’s discarded.

CB:

You seem like you’re in a good place right now — especially given Swans’ sometimes tumultuous history.

MG

:For now I feel like what I’m doing is what I was put on earth to do, and so I just follow it. By nature I’m kind of a histrionic character, so I’m a natural performer and I love being in the moment and being like a puppet to the music.

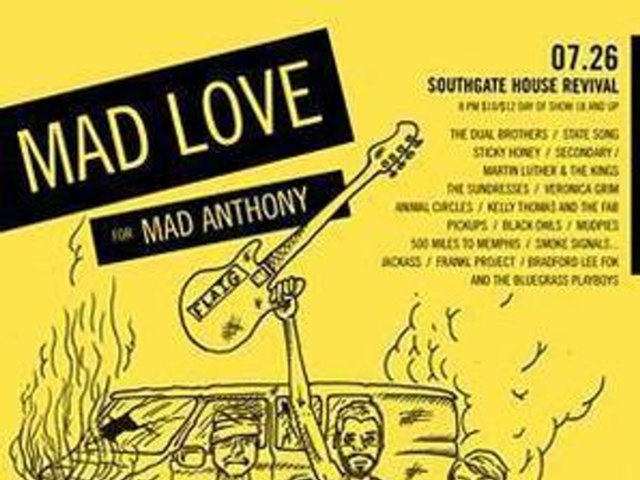

SWANS play the Southgate House Revival Tuesday (July 23) with Pharmakon. Purchase advanced tickets here.