As many people know all too well, locking down a job with generous pay and benefits takes you through an American Ninja Warrior-style obstacle course of proving your educational record, showing work skills and surviving a barrage of interviews. But when an insider — a family member or another connection — shows you a shortcut, why bother with the usual apply-and-hope route?

Historically, that inside track is well-worn in local government across the country. Taxpayer-funded jobs often go to people as much for their personal and political linkages as their work credentials — if not more so. Even critics concede that the winners of elections reap the spoils. Jobs are some of those spoils.

Last fall, CityBeat decided to see how nepotism, political patronage and cronyism played out in Hamilton County. We obtained the lists of employees in all county offices. We spoke with more than two dozen current and former county officials, current and former employees and local attorneys — Democrats and Republicans. We verified as many relationships as we could.

If a scent emerged, it came straight from the county courthouse. There, CityBeat found 63 employees who fit the mold. Most had a relative already in elected office or on the courthouse payroll when they were hired. Others were Republican Party honchos or suburban officeholders. A few cases were anomalous. In one, a lawyer and her fiancé were hired by an elected officeholder who worked, on the side, for the lawyer’s father. A new hire is the son-in-law of county Democratic Party Chairman Tim Burke.

None of the hires fall under the state’s definition of nepotism. Ohio law makes it a felony for public officials to hire — or authorize or influence the hiring of — a family member into a public job. “Family member” includes children, parents, siblings, grandchildren, grandparents, stepparents, stepchildren and any person related by blood or marriage who lives in the same home. Ohio officials can hire all the cousins, nieces, nephews, uncles, aunts and in-laws they want, as long as they live apart. And officials can hire each other’s relatives till the cows come home, unless influence was part of it.

The Family Way

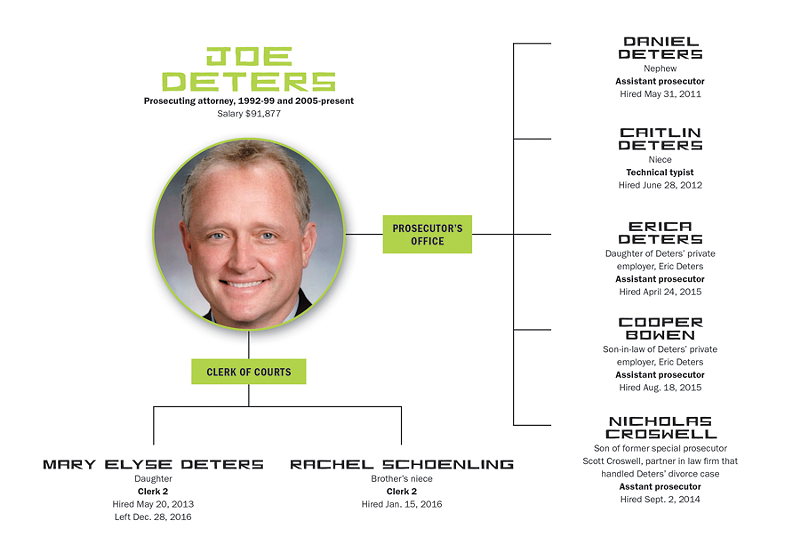

In Hamilton County, two offices stand out in their insider hiring — those of Prosecuting Attorney Joe Deters and former Clerk of Courts Tracy Winkler, who left office in January after her re-election defeat. Both are Republicans.

Take Deters, who served as prosecutor from 1992 to 1999, regained the job in 2005 and has held it ever since. Of his 186 employees, CityBeat identified 31 who were related to past or present county officials or employees or had political or business linkages with Deters at the time of their hire. Among them was Thomas Grossman, chairman of the Warren County Republican Party and the son of a retired Hamilton County judge when he was hired in 2009. Another was Michael Florez, a longtime Republican Party operative hired in 2005. Both are assistant prosecutors. Both are paid $119,480 a year.

Other hires were more tribal. Deters hired a nephew, Daniel Deters, in 2011 and a niece, Caitlin Deters, in 2012. Daniel is an assistant prosecutor making $56,650 a year, Caitlin a typist making $30,900. Deters’ daughter Mary Elyse, meanwhile, was hired by Winkler as a part-time clerk in 2013. She left that job Dec. 28. Rachel Schoenling, the niece of Deters’ brother and former Municipal Court bailiff Buzz Deters, still holds a clerical job in the clerk’s office.

Deters’ employment largess extends to even farther-flung Deterses. Deters declared himself a part-time prosecutor in 2009 so he could moonlight on the side. In 2014, he went to work for suspended lawyer Eric Deters on lawsuits filed for former patients of fugitive doctor Abubakar Atiq Durrani. The two Deterses are not related. The following April, Joe Deters hired Eric Deters’ daughter Erica Deters as an assistant prosecutor. Four months later, he hired Erica Deters’ fiancé Cooper Bowen, also as a prosecutor. Married that September, they both make $56,650.

Eric Deters says the hire of his daughter and son-in-law stemmed from his 30-year friendship with Joe Deters, not his hiring of the prosecutor for legal work.

“Erica and Cooper both just became lawyers. They worked for me for a year. They are outstanding,” Eric Deters says. “Both wanted to do public service. I asked Joe if he needed any lawyers. He said I got lucky. He did. Both applied. Both impressed. Both were hired. Both are doing great.

“Joe told me he has always relied on referrals from those he trusted because only once in all his hirings did it fail him,” he says. “If Erica and Cooper sucked, they wouldn’t have been hired. Brilliant young minds. And neither needed the job. They could have worked at and still work at Deters Law Firm.”

Winkler, during her five years in office, served as a textbook example of legal nepotism and political patronage. In October 2011, she was the wife of one Hamilton County Common Pleas Court judge, Ralph “Ted” Winkler, and the sister-and-law of another, Robert Winkler, when county Republicans handed her the vacant court clerk job, which pays a cool $100,000 a year. At the time, she was also on the Green Township Board of Trustees and was its chairwoman during a controversial event in 2010 — the township’s hiring of a new, $50,000-a-year executive assistant. Who got the job? The wife of Hamilton County Republican Party Chairman and former Common Pleas Judge Alex Triantafilou.

Once in office, Winkler opened the patronage spigots. Two weeks into the job, she hired her nephew Ryan Glandorf — whose father Roger Glandorf is a Common Pleas Court bailiff — as an auto title clerk for $22,382 a year. The next month, she made Tony Rosiello, a Republican just elected to the Green Township board, her chief deputy for human resources. In 2014, she hired Jeff Baker — president of the Colerain Republican Club — as a clerk.

That’s when Winkler became a job creator for extended clan members. Late in 2014 she hired cousin Kenneth Brinkmeyer as a court bailiff. The following June she hired her nephew John Trimble as a clerk. Two months later she hired Jonathan Bauman, the brother of her daughter’s husband, as a $55,000-a-year “fiscal officer.” And in March 2016, Winkler hired Carolyn Brinkmeyer, who is married to another cousin, as a clerk.

One favor begets another. This past January, Deters reciprocated Winkler’s earlier hiring of his daughter. Winkler’s daughter Andrea Boettcher was available for hire because her previous employer, Dennis Deters — Joe’s brother — lost his election and left office. Joe came to the rescue and hired her as an administrative assistant. The job pays $37,500 a year.

Hiring by What? Merit?

In effect, the courthouse is like a scale model for ancestry.com, with overlapping branches of multiple family trees. Some in the community have grown weary of the absence of a formal merit system in the county courthouse. Robert Newman, who has practiced law in Cincinnati for about 45 years, called the hiring of family members a “pernicious” practice.

“Sure, there are some sons and daughters and nephews and nieces who were likely hired because Dad was a judge or a prosecutor and who are performing well on the job,” Newman says. “But some are not and are less qualified than others who applied or who could have gotten the job if the employment process were an open one.

“So they work side-by-side with people who are doing the job and they are not,” he continues. “This does not do them any good. It doesn’t do the office any good. It is not fair to taxpayers. It is just bad personnel policy. Most businesses have policies against nepotism for these reasons.”

Aftab Pureval, a political outsider who in January became Hamilton County’s first Democratic clerk of courts since 1903, ran on a platform of depoliticizing the 220-employee office. In his first three months in office, he fired Rosiello, Baker, Bauman, Trimble, Carolyn Brinkmeyer and Annie Boitman, a deputy clerk who leads the Delhi Republican Club.

Under Winkler, the clerk of courts office had no written policy for posting job vacancies and hiring — one that could be found, anyway. Winkler’s office did not provide one in response to a CityBeat public records request. Pureval offered to deliver it upon taking office, but could never find it. Winkler could not be reached for comment.

Pureval, for the most part, has been hiring people free of the stench of patronage. The native of suburban Dayton, who quit his job as a Procter & Gamble attorney to become clerk of courts, says he posted job openings online and conducted competitive interviews. In February, he announced the hiring of a chief financial officer from General Electric, an information technology director from Fifth Third Bank and a human resources director who had worked at Welltower Inc., a Toledo-based operator of senior living centers and health care clinics.

“My charge coming into this office was to change the culture,” Pureval says, “and the way that I’m doing that is by recruiting the most qualified people to serve in this office. The three folks that we announced this week all come from Fortune 500 companies. They’re frankly the best of the best.

“We got applications from all over the country,” he says. “We had folks from Lorain County apply and we had folks from the West Coast apply. We were able to reach a broad audience to get the best talent. The results speak for themselves. These are folks at top private companies who wanted to come to the clerk’s office. That’s unheard of.”

Pureval didn’t ban the hiring of people with the right lineage entirely. His new $87,500-a-year chief compliance officer, Chris Wagner, is the son-in-law of Hamilton County Democratic Party Chairman Tim Burke. Pureval says he had “no involvement” in Wagner’s hiring. Wagner actually has a contradictory aspect: In his nine years of managing the Ohio Attorney General’s office in Cincinnati, the last six were under Republican AG Mike DeWine.

Policy? What policy?

As one might expect, Hamilton County’s administrative office on Court Street serves as a hub for many of the human resources services for county employees. Its 265-page personnel manual is laden with policies, procedures and benefits. The rules for filling job vacancies are rigorous. The human resources department, for example, must sign off on applicants’ qualifications before they can be hired.

But this is county government. It reeks of the 19th century. Other than judges, Hamilton County has 11 elected officeholders who are their own bosses. Why a government would have elected court clerks, recorders and engineers in 2017 is a question for another day. Suffice to say, how they go about hiring and firing is entirely up to them. That is, as long as it’s legal and not discriminatory in any way.

CityBeat sent public records requests for the written hiring guidelines of various courthouse offices. Just like the clerk of courts, prosecutor Deters does not have any. Nor do the courts. Common Pleas Court Administrator Patrick Dressing said the courts must abide by the state constitution and hire on the basis of “merit and fitness.” Deters’ spokeswoman Julie Wilson said her office simply follows state and federal law in hiring.

Deters’ discretion in populating his office comes down to this state law: “The prosecuting attorney may appoint any assistants, clerks and stenographers who are necessary for the proper performance of the duties of his office.”

Translation: As long as he doesn’t break the law, Deters can hire whoever he damned well pleases.

CityBeat wanted to ask Deters if it was purely coincidental that at least one-sixth of his staff came aboard with one kind of connection or another. He turned down CityBeat’s request for an interview. Notification came from an assistant prosecutor, Michael Friedmann, who was one of those with an inside connection when he was hired in 2011. His father, assistant prosecutor Roger Friedmann, has worked in the office since 1976.

The exhaustive personnel policies of the Board of County Commissioners are meant to deter such premeditated hiring. Openings must be posted at least 10 days. They should be filled, whenever possible, by qualified county employees. Candidates are evaluated by Human Resources. Then department heads choose finalists, conduct interviews and choose the “best-qualified” applicant based “solely upon merit and fitness.”

In her six years as the county’s human resources director, Cheryl Keller says she recalls no discussion of standardizing hiring practices across elected county offices. She says her office has no control over how other elected officials advertise and fill their jobs. Deters’ office, she says, does not post jobs on the county’s main jobs page. Nor did the court clerk’s office until Pureval took over. The county’s main human resources office, Keller says, does not monitor other county offices for hiring that skirts the line of nepotism.

“I really don’t know who gets hired in other agencies to know if they’re related to anybody,” Keller says. “I don’t know that anyone’s ever tried to look at that.”

Does anyone? The Ohio Ethics Commission does. When a public official in Ohio violates the state nepotism law, enforcement falls to the OEC, in Columbus.

“Giving precedence or advantages to a family member in public hiring decisions is unfair to other applicants who may be equally or even more qualified,” says OEC Executive Director Paul Nick. “Public agencies should spend public dollars to hire the most qualified candidates and not those with the best family connections.”

It was the OEC that investigated a former West Clermont County school superintendent for recommending the district’s hire of a son, a daughter, a son-in-law and a daughter-in-law. In 2014, the OEC reached a settlement with Gary Brooks instead of trying to put him in prison or levy fines as the state nepotism law allows. Brooks retired and agreed not to repeat the offense if he ever returns to public employment. He also agreed to accept a public reprimand, which was devoid of shame value because the OEC did not disseminate it to any news media or even post it on its website.

Who’s a “Family Member?”

Such overt acts are pretty much where the Ohio nepotism law stops. Beyond that, Ohio is completely cool with officials’ free-wheeling hiring of the clan members of employees or business associates. Nothing prevents public officials from hiring each other’s relatives.

Ohio courts have upheld the status quo. Nick cites two instances of state courts quashing attempts to put the kibosh on blanket “no relatives” policies. In 1983, he says, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that the city of Fairborn’s policy violated its charter requirement to hire on the sole basis of merit and fitness. In 1996, he says, the Fifth District Court of Appeals ruled that Delaware County lacked the statutory authority to ban all hiring of relatives.

So Ohio keeps the door open for the broader form of nepotism. Mary Rita Weissman, a partner at The Weissman Group human resources consulting firm in Dayton, says that, ultimately, it can lead to “serious problems.”

“If you’re going to hire a person just because they are a relative of somebody, chances are you’re also going to rate them just because they are the relative of somebody, you’re going to promote them just because they are the relative of somebody and you’re going to give them wage increases based upon them being the relative of someone,” she says. “The first decision taints everything that comes after.”

Strict, qualifications-based hiring weeds out much of the favoritism. But nepotism laws elsewhere demonstrate that Ohio’s restrictions are entry-level.

The federal government, for one, includes nephews, nieces, uncles, aunts, first cousins, in-laws and half-siblings in its nepotism ban. Texas extends its hiring ban to nephews, nieces, uncles, aunts, immediate in-laws and great-grand-relatives. Pike County, Ky. — site of the internecine Hatfield-McCoy feud — goes one further than Ohio by banning officials from hiring their in-laws.

No place, though, appears to take nepotism more seriously than the state of Missouri.

Missouri’s nepotism ban forbids public officials at any level of government from hiring relatives within four degrees of separation by blood or marriage. In other words, no one as far removed as cousins, great nieces and nephews and great-great-grandchildren.

James Klahr, executive director of the Missouri Ethics Commission, says the ban — in the state’s constitution for more than a century — has caused problems in locales with small labor pools.

“But it’s still on the books, and I’m not aware there’s been any effort by anyone to change or minimize it,” Klahr says. “I think people want to feel like they’re being hired for their merit, not because they’re somebody’s nephew or uncle or what have you.”

But discussion of clamping down on awarding county jobs as favors to family, friends and political allies appears to be a non-starter in Hamilton County. As one might say, it’s sooooo Cincinnati.

Justin Jeffre, the 98 Degrees band member who ran for mayor on a reform ticket in 2005, is now on the board of directors of Common Cause Ohio, a nonprofit group that seeks to hold power accountable. He says the selective hiring in the county courthouse is a conflict of interest.

“I think most people would agree that that’s not acceptable,” Jeffre says. “It’s hard to believe they’re so blatant about doing this again and again.”

The prosecutor’s office's lack of written policy on posting job vacancies and hiring manifested itself as recently as January. Deters hired Tracy Winkler’s daughter Andrea Boettcher as an administrative assistant on Jan. 12. CityBeat sent the office a public records request for that job posting. The written response from Michael Friedmann?

“Our office does not have any records that would be responsive to your request.”

University of Cincinnati journalism students Lauren Moretto, Monroe Trombly and Huy Nguyen provided research assistance for this report.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that attorney Eric Deters was disbarred at the time Joe Deters went to work for his firm. Eric Deters was suspended, not disbarred. We regret the error.