S

even-month-old pit bull mix Oreo, dark chocolatey brown with all-white paws, was, at one time, the “miracle dog.”

In 2009, Oreo’s owner hurled her from the roof of his sixth-story Brooklyn, N.Y., apartment. Her tale was picked up nationwide when the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) took her in to treat her near-fatal injuries.

After months of treatment and rehabilitation, Oreo finally got back on her feet — but not before the ASPCA issued a statement that Oreo had become aggressive and was going to be killed. Among thousands of frantic pleas to give Oreo a chance, a nearby animal sanctuary, Pets Alive, offered to take in Oreo for rehabilitation; it’s not unusual for a dog to emerging from a situation like Oreo’s to react with some temporary aggression.

She never made it there — she was killed on Nov. 13, 2010.

Two New York state legislators subsequently lobbied for “Oreo’s Law,” legislation that would make it illegal for a shelter in New York to kill an animal if a certified rescue group or no kill shelter offers salvation. The ASCPA, however, vehemently — and successfully — lobbied for its defeat, leaving impassioned animal welfare advocates across the country asking, “Why?”

That’s one question advocates of the steadily growing No Kill movement continue to ask as they seek to overturn traditional euthanasia philosophies at shelters nationwide in hopes of saving millions of animals’ lives.

Today, about 200 cities and 54 communities have embraced the No Kill movement, which has taken a proselytizing approach to spreading its methodology in communities nationwide; the Great Shelters Conference, which took place Sept. 15-16 in Blue Ash, marked the second annual locally coordinated effort to spark dialogue and lobbying efforts for local no kill implementation. Eleven states were represented by 149 animal rescue advocates during a series of lectures, panels and networking sessions.

Pioneering No Kill

There’s no doubt about it: Americans love their pets. So much, in fact, that we spend $50 billion on our animals each year, according to the American Pet Products Association.

Nathan Winograd, keynote speaker at the Great Shelters Conference and executive director/founder of the No Kill Advocacy Center, is convinced that even amidst a volatile political climate, loyalty to our pets is one fixed nonpartisan issue.

“If you look all around the country, we’ve got no kill communities that are urban and we’ve got rural communities. ... We’ve got no kill communities that are in very conservative parts of the country and in left-leaning parts of the country.”

Winograd pioneered the No Kill movement when he founded the Advocacy Center in 2004; he noticed that shelters across the nation were under-utilizing programs whose effectiveness he was certain could be amplified to prevent innocent animals from dying.

The No Kill movement defines a successful no kill shelter as one saving at least 90 percent of its animals — the other 10 percent are deemed hopelessly ill or too violent for rehabilitation — through the use of an eleven-step “equation” developed by Winograd in 2005 to create the nation’s first no kill community in San Francisco. A no kill community is simply an amalgamation of shelters in one geographic area working under the no kill philosophy.

The movement is founded upon the idea that the conventional wisdom upon which traditional kill shelters are founded isn’t just wrong, it’s immoral.

Eleven Steps

What is perhaps most interesting about the No Kill movement’s eleven-step equation, the one celebrated and preached by convert shelters from Austin, Texas, to Reno, Nev., to Boone County, Ky. — is that it’s rather unremarkable. None of the eleven steps appear magical or groundbreaking: According to Winograd, use of the eleven-step equation isn’t an “A-ha” solution to ending shelter euthanasia, but simply one that makes intuitive sense. In Oreo’s case, the difference between life and death could have been as simple as regularly accepting the help of legitimized, eager rescues.

“You have shelters killing animals at taxpayers’ expense when private non-profit organizations are willing to save that animal at their own expense. It’s that kind of antagonism that causes the friction — the refusal to collaborate,” Winograd says.

“It’s not that there’s a magic wand or some secret way that they interact. They’re common sense programs,” Winograd says. “We’re doing the best we can’ just doesn’t fly anymore.”

Kill vs. No Kill

Traditional “kill” shelters — such as the Cincinnati SPCA — are usually open admissions, meaning they’ll take in any animal surrendered to the shelter regardless of space or the animal’s health or temperament problems; that means many animals face the needle to free up kennel space before they’re even displayed for adoption.

Limited admission shelters are more selective in which animals secure a spot in the kennels; once cages are filled, excess animals are denied regardless of circumstance. Representatives from the Cincinnati SPCA, including board member Jim Tomaszewski, attended the conference to build relationships and collect ideas.

“These aren’t new, groundbreaking ideas,” Tomaszewski says. “We could be doing better at a lot of these things.”

And they’re working on it; overall adoptions rose 56 percent from 2011 to 2012 after improving rescue and foster liaisons and lowering adoption rates. Still, there’s great room for improvement. According to 2011 Cincinnati SPCA data, the Cincinnati SPCA took in 9,025 cats; 1,307 (about 14 percent) were adopted. Dogs fared better; 8,209 were taken in, while 3,151 were adopted (around 38 percent).

Requests for Cincinnati SPCA’s euthanasia procedures and criteria were not fulfilled by press time. The SPCA’s website outlines which percentages of animals were deemed “not adoptable” due to health or temperament issues; unregulated, hazy standards left up to individual shelters and could be something as minor as a dog being an unpopular color, breed or affected by blindness or allergies.

Making the Change

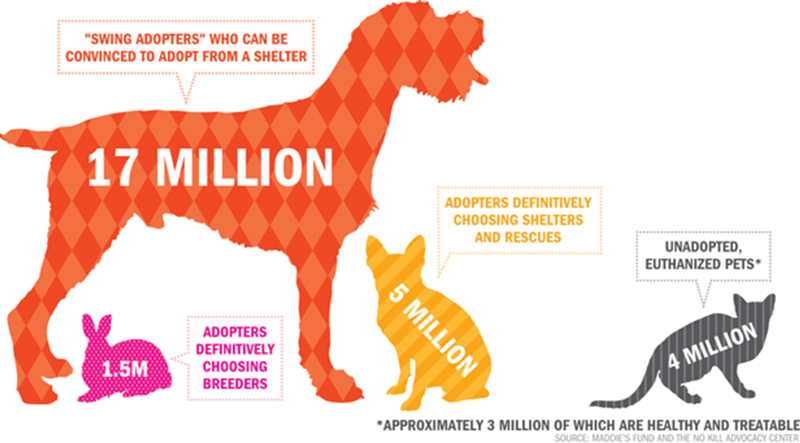

According to the No Kill Advocacy Center, roughly 23 million Americans are considering adopting a new dog or cat into their home each year; 17 million of those are “swing adopters” — they have not decided from where they’ll get their new pet and can be swayed to adopt from a shelter. Four million shelter animals are euthanized each year, meaning attracting less than 25 percent of those adopters would be enough to fill the gap and end needless euthanasia nationwide.

For Beckey Reiter, shelter director at the Boone County Animal Shelter in Boone County, Ky., since 1994, the transition was molded from a more practical standpoint.

“The rates of cats coming into our shelter were increasing every year. We were trapping and euthanizing entire litters of kittens and it wasn’t working. … I had a staff member come in in tears because she couldn’t stand to euthanize another kitten. I thought, ‘There has to be an answer.’ ”

Reiter attended the first Great Shelters conference in 2011 after she read one of Winograd’s books; the dialogue inspired her to institute extreme policy changes at her shelter, whose save rate stood at 53 percent in April 2011; as of April 2012, it increased to 80 percent.

“There’s more stress now — but that’s because everyone is striving in a different direction,” Reiter said at the conference Saturday. Reiter’s shelter has experienced bumps in revenue, adoptions, volunteer participation and doubled donations following a public commitment to implementing the no kill equation.

According to Winograd, that stress is a small price to pay for the benefits.

“Is it too much to ask that the organizations that not only we fund with our tax dollars but that we fund with our philanthropic dollars — is it too much to ask them to be creative? I don’t think so.”

For information on the national No Kill movement or details about the No Kill equation, visit nokilladvocacycenter.org.