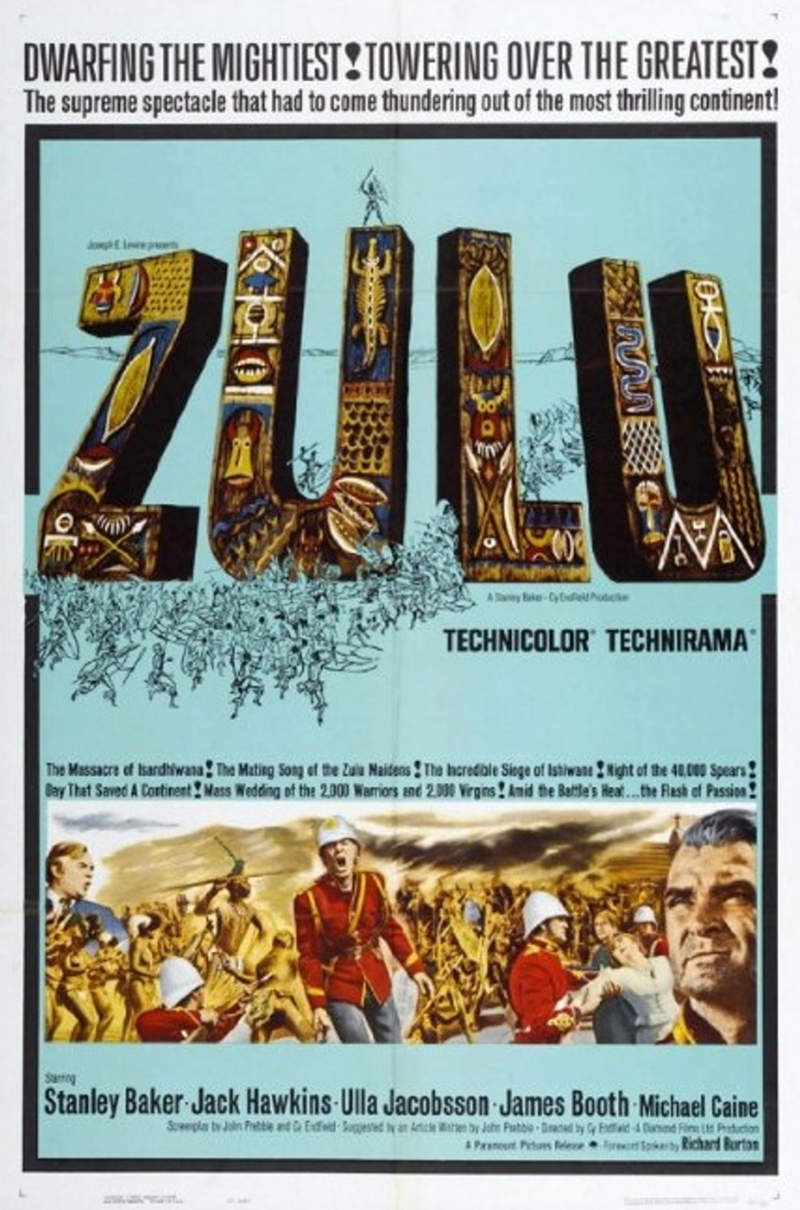

When I mention war films, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? Probably titles like Saving Private Ryan or, more recently, something like the controversial and much-debated American Sniper. But what if I ask about British war films? Maybe you’d think of Lawrence of Arabia and one or two others. What about the 1964 film Zulu? I’m going to guess that not that many are familiar with this one, let along the actual Anglo-Zulu War. But you don’t really need to know all the ins and outs of the conflict to enjoy and appreciate this movie.

The movie is based on the 1879 Battle of Rorke’s Drift, in which roughly 150 British and Welsh soldiers faced off against an overwhelming number of Zulu warriors at a mission station in southern Africa. In a lot of ways it’s almost the British equivalent of the Battle of the Alamo — the difference in this case being the British soldiers won their battle, whereas all the defenders of the Alamo died.

Let’s get this out of the way: Yes, there are a lot of historical inaccuracies in the movie. But anybody who has ever seen a “Based on a True Story” movie should be aware of that by now.

To me, some of the best war films out there are not the ones that are overly patriotic and about ‘us vs. them,’ but ones that show us who the people are on both sides or, at the very least, films that don’t broad-brush the other side. With Zulu, we get that. Neither side is portrayed as the hero nor the villain; they’re two powerful forces, in their own way, who duke it out in combat. Both are proven to be worthy adversaries who don’t give up without a fight.

One thing I love about this film is the use of sound. The movie seems to use chats, songs and sounds as a motif about the sides. Probably the most effective use is when the Zulus arrive, coming over the ridge making a huge clatter with their assegai (short spears) and shields. One of the officers in charge, Gonville Bromhead (played by Michael Caine in his first film), says that it sounds, “Like a train…in the distance.” This comparison works rather well. It’s this constant clamor created that gives the audience an idea that the British are up against an almost unstoppable force. And when the near 4,000 Zulus pop up on the ridge, it seals the envelope.

Along with the drumming, the Zulus also have their own war chants which are another form used to intimidate the defenders, but on the morning of the second day the defenders reply with their own battle cry, the military march “Men of Harlech.” I see this as director Cy Enfield’s way of showing that even though these men are in a war against each other, they do have similarities. But the beautiful medleys of the British and Zulus are disrupted with the continuous roar and volley of rifle fire. And at the end of the battle many lay dead; although they are victorious, there’s no cheers to be shouted. But the Zulus do offer a final chant of respect to their worthy adversaries.

At the end, Bromhead is asked by the more experienced officer John Chard (Stanley Baker) what he thought of his first action. Bromhead replies with “Sick,” and Chard follows it with, “You’d have to alive to be sick.” A clever indication of the creative team’s thoughts on war.

There are many other great things to say about the film. The dynamic between Baker and Caine is fantastic, and supporting performances from James Booth as the drunk, petty thief Henry Hook (one of the controversial inaccuracies) and Nigel Greene as the tough but kindhearted Colour Sgt. Bourne are great. The performances from then-Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi and his people are impressive. Also the cinematography by Stephen Dade is gorgeous, he makes every shot interesting. It almost reminds me of a John Ford Western.