Twenty years ago this month images from Rwanda were telecast around the world, and they were images of bones — bones bleached white by the sun and drained dry of blood and flesh — littering roadsides, piled in open graves, stacked in abandoned churches and markets and washed up along the shore lines of small bodies of water.

They were the bodies of Tutsis who, though minorities in number, had been deemed at the turn of the 20th century by German and Dutch colonists to appear more “Caucasian” and were therefore given more political power over their Hutu brethren who spoke the same language, worshipped the same god and even intermarried.

The Hutus spent another generation fuming, seething, plotting and even fluidly “becoming” Tutsi when it suited their needs; some Tutsis also “switched” to Hutu when the need arose.

Otherwise, these people lived and worked together in Rwanda, a nation roughly the size of New Jersey.

In mid-April 1994, the three-month systematic and well-planned genocide by machete, gunfire and rape of one million Hutu Rwandans jumped off after the airplane of then-President Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down and Hutu paranoia spread across Rwanda via national radio and television broadcast urging Hutus to kill their Tutsi friends, neighbors and relatives.

In America, we received all this news quite late, as we do with most atrocities from the continent of Africa. And as I recall, we did nothing but watch, and soon the shelf life of the story grew rancid and our nightly newscasts discarded it and moved on to something else.

I did not understand the complexities of tribal names and loyalties or the class standings of farmers versus the educated in this part of the world and so I started to try to read Philip Gourevitch’s dense, frightening and thoroughly reported literary journalism dispatches from Rwanda in The New Yorker.

Deciphering the system set up to slaughter a million countrymen, women and children in three months actually made me swoon and I could no longer read those stories.

In my feeble attempts to tether American ignorance (Rwandan genocide) with the consumption of popular culture (my column back then), I’d work Hutu and Tutsi references into my sentences.

By the time that column was running, tribunals and trials were underway for the hundreds of Rwandans ferreted out as masterminds and ringleaders of the genocidal rampage, so the story was back in the news and still new to many Americans.

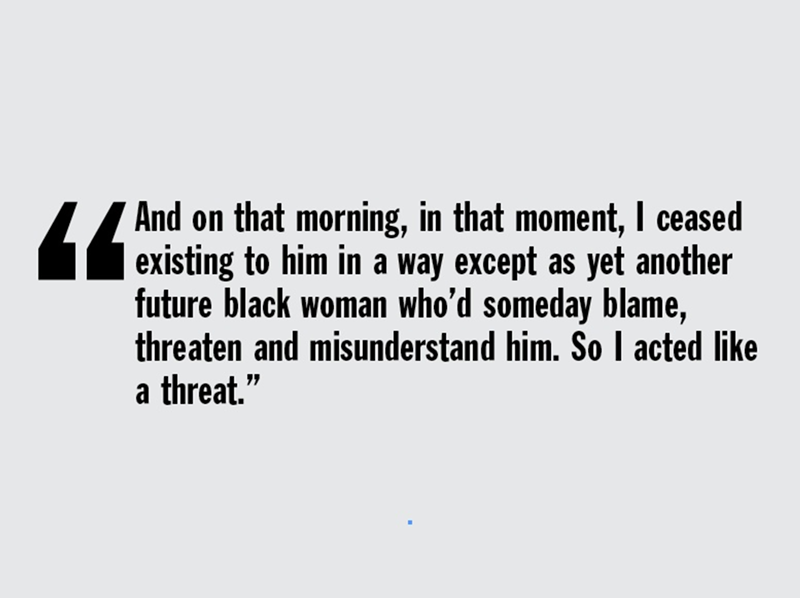

“Like a Tutsi in a Hutu village” was the simile I came up with to describe mine or someone else’s Otherness in reductive sociopolitical pop babble. Then, later, thinking I was the most clever writer to ever do it, sometimes I’d flip it to “Like a Hutu in a Tutsi village” to describe someone’s blind wrath or anger.

Admittedly I have written countless cringe-worthy phrases and sentences trying to get at the essence of some behaviors — man’s inhumanity to man, as we learned it in high school literature classes reading the classics by Dostoyevsky or Melville.

Mostly, though, my Rwandan references in retrospect are just lazy and diminishing.

One million people gone at the hands of their own people.

The closest comparison nearest to helping us make sense of this is, of course, Adolf Hitler’s massacre of the Jews; however, Hitler made a production out of religious differences while mocking and shaming the Jews for their physical appearances.

Not so in Rwanda.

They could even only tell who was who because families were required to register themselves as Hutu or Tutsi.

What Rwanda does share with Nazi Germany is what Rwanda President Paul Kagame has called the creation of “some level of insanity” among soldiers who’d come across — post-genocide — the extremist Hutus who’d murdered and raped their entire families and who were now repatriated and allowed to reclaim their land and even their social standings.

Some of those soldiers, led by Kagame from Uganda into Rwanda to quell the killing, merely killed those Hutus or killed themselves because they were now alone in the world.

Worse still were the brutal, animalistic rapes of Tutsi women.

Their breasts were cut off; some were pregnant and gave birth mid-rape and their babies were speared as they came out of the womb; women were raped with all kinds of implements, including machetes.

Seventy percent of Tutsi women raped who survived were infected with HIV and it’s now believed the Hutu government began releasing male AIDS patients from Rwandan hospitals in the weeks before the genocide to amass “battalions of rapists,” according to President Kagame.

And there are 5,000 documented children born of the rapes who live now with that stigma in a nation that prides itself on sexual chastity and the exaltation of women as pure.

But perhaps the most chilling story to come from the Rwandan genocide is that Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, the nation’s minister of family and women’s affairs, encouraged the savage rapes of women in Butare, a town dense with Tutsis, and she did it with the Interahamwe, savage marauders whose name translates to “those who attack together.”

She began her crusade by announcing via loudspeaker along the back roads of Butare that the Red Cross had come with food and sanctuary and that Tutsis should make their way to a nearby stadium. When they arrived the Interahamwe were there to rape and murder while Nyiramasuhuko watched and ordered the men to rape the women, whom she called “dirt” and “cockroaches.”

What good came of all this?

Documentation.

Gourevitch published a book: We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families: Stories from Rwanda.

The New York Times documented Nyiramasuhuko’s infamy as the first woman in the world charged with rape and genocide. Shockingly, she is of Tutsi descent.

Tutsis still receive reparations from the Rwandan government, even counseling, as that nation observes the 20th anniversary of its genocidal past.

And I’ve dedicated myself to never writing another lazy self-serving sentence.

CONTACT KATHY Y. WILSON: [email protected]