The two forward rolls got everyone’s attention the night of June 26, but something else occurred that fans hadn’t seen before, and it had nothing to do with grade school tumbling. After recording his ninth save of the season against the Milwaukee Brewers — and following the double somersault — Aroldis Chapman smiled. As much as it was a demonstration of happiness or joy, it appeared to also be a smile of relief, and contrasted sharply with his normally stoic expression.

Two months into the 2012 baseball season, the Cincinnati Reds relief pitcher was flying high. The Reds made Chapman — nicknamed the Cuban Missile because of his 105-mph fastball — their closer, and he proved them right by holding other teams scoreless over 24 games. Then the Missile seemed to hit a blockade, and mortality set in. During a seven-game derailment in mid-June, Chapman gave up eight earned runs, served up three home runs, blew three saves and lost four games. Reds fans were worried, only to be reassured by Chapman’s three-strikeout, two-somersault save over the Brewers on June 26. And when Chapman was named to the National League All-Star team, joining Joey Votto and Jay Bruce, his lapse from invincibility was all but forgotten.

In the Reds’ front office, though, worries about Chapman persisted. Not about his choice or location of pitches. About other stuff, like his compliance with traffic laws and his choice of companionship. Some insiders fear that the 24-year-old Cuban’s personal life is approaching, well, the velocity of his fastball.

Go back to May 20. Chapman was named the Reds’ closer that day, and he struck out Andruw Jones with a 98-mph laser to save a 5-2 win at Yankee Stadium. Just 10 hours later, he was posing for a mug shot at the police station in lowly Grove City, Ohio, just south of Columbus. The ticket says he was driving his 2010 Mercedes S63 at 93 miles per hour in a 65-mph zone on I-71. A camera in the officer’s car captured Chapman, who speaks limited English, saying he was picking up his “girlfriend” at the Columbus airport. What made matters worse was that a check with police databases showed that Chapman’s Kentucky driver’s license had been suspended a week earlier. Grove City wants him back on July 18, this time in court.

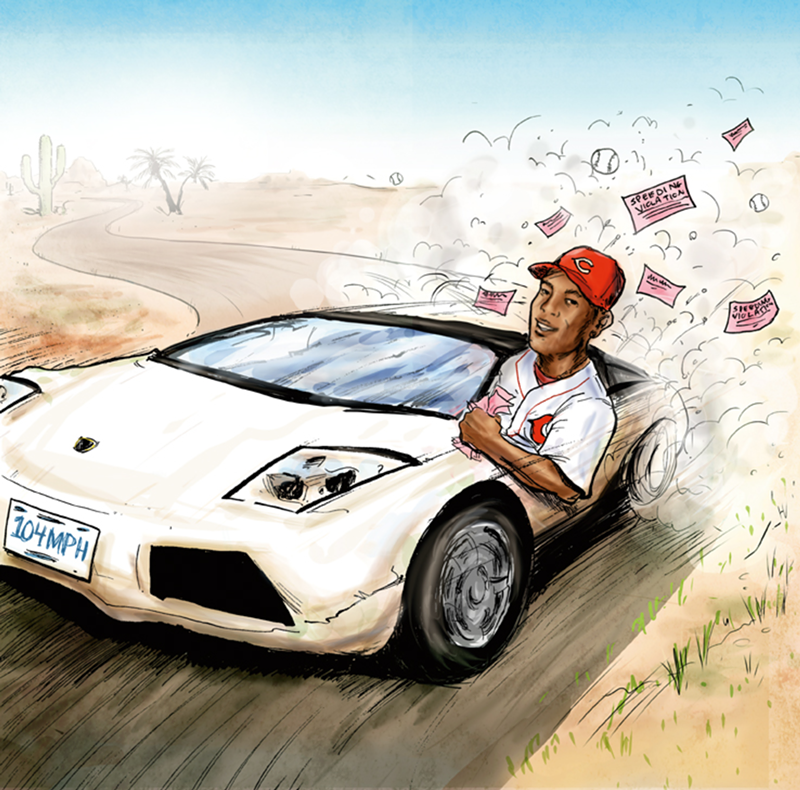

Operating a car with a top speed of 155 would cause most people to catch the wrong end of a radar gun. Chapman finds speed traps wherever he goes. Since joining the Reds’ minor league team in Louisville in 2010 and receiving his first U.S. driver’s license that June, Chapman has racked up six speeding tickets in four states, three in the Mercedes, three in his 2010 Lamborghini Murcielago, not the kind of car that sputters up the Cut-in-the-Hill. Because two of the tickets were issued in Kentucky in a 12-month span and involved speeds 15 miles over the limit, the state’s Division of Driver Licensing ordered him to attend a hearing in Louisville in June 2011. Chapman was a no-show, so the state revoked his driving privileges for six months.

Kentucky restored the license this past Jan. 11. Assume it was effective at 12:01 a.m. because Chapman was ramming his Lambo down I-95 in Miami at 6 that morning. Miami-Dade Police clocked him at 95, 40 miles per hour over the speed limit. His failure to make a March 1 court appearance in Florida triggered another license suspension in Kentucky, the one that Grove City came upon on May 21. Once Chapman made up with the Florida court and paid a $385 fine, Kentucky lifted its suspension on May 22.

By the time the Florida matter was resolved, Chapman had rejoined the Reds at their spring training camp in Goodyear, Ariz. His choice of wheels was the Lamborghini, and it was the Murcielago that Goodyear police caught doing 75 miles per hour in a 45-mph zone on Feb. 15. Chapman paid a fine of $235, bringing the cumulative cost of his speeding habit to $1,200.

Luckily for Chapman, excessive speeding in other states can’t lead to another revocation of his Kentucky driver’s license. “Since they occurred out of state, they don’t show up in our database,” said Ryan Watts, spokesman for the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. “State law prohibits us from using out-of-state citations against his points record.” The same goes for Ohio, said a spokeswoman for the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles.

Likewise, Chapman’s speeding infractions have no bearing on his immigration status.

“For somebody that is here legally, minor traffic offenses would not trigger enforcement action,” said Khaalid Walls, a spokesman for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

While his legal status isn’t in doubt, sources say his agents have asked him to simply stop driving, advice he has chosen to ignore. From most reports, in Cuba he didn’t own a bike, much less a car. In the United States, he bought a car before he had a license.

Cincinnati lawyer James Bogen defends people who are accused of crimes and traffic offenses. He said there are two main types of speeders — those who are late and trying to get somewhere too quickly and those who are hooked on the thrill of driving above the speed limit.

“If you’re somebody who just wants to drive the speed limit, you’re not going to drive a Lamborghini,” Bogen said.

Making it clear that he wasn’t talking about Chapman specifically, Bogen said chronic speeders rein it in at different thresholds. Typically, he said, people slow down when the cost and inconvenience of fines and license suspensions reach a breaking point. Others, he said, don’t stop speeding until they’ve hurt or killed somebody.

“Police officers are under the firm belief that speed kills,” Bogen said. “If my son, when he gets older, drove like that, I would take the keys away. At some point, driving fast like that, under the right circumstances, could be considered reckless driving.”

Coming to America

Although his appearance in the World Baseball Classic was three years ago, Albertin Aroldis Chapman de la Cruz remains somewhat of an enigma. He hurls 100-mph fastballs with the intent of rendering hitters impotent, but bouts of wildness have at times made him look out of place on a Major League mound. Cuban players have not always lived up to their hype, but technology of greater sensitivity and accuracy has made it possible to distinguish pretenders from the real deal. During the World Baseball Classic, Chapman’s alleged 102-mph fastball was no longer based on a scout’s estimation or the reading of a hand-held radar gun; it was verified by advanced camera system technology now used in every Major League Baseball stadium.

His personal life borders on tragedy. When Chapman bolted from the Cuban national baseball team in the Netherlands in July of 2009, he left behind his mother, father, two sisters, girlfriend and a newborn baby daughter, Ashanti Brianna, all of whom are forbidden to leave Cuba. Last month, Ashanti celebrated her third birthday, but Chapman has never held his daughter. Holding pictures of her is as close as he’s ever been — she was born while he was on the trip that would eventually provide his means of escape. After ducking into the waiting car of an acquaintance in the Netherlands, Chapman established residency in Andorra before coming to the U.S.

That January, the Reds surprised the baseball world by outbidding the likes of the Yankees and Boston Red Sox in the Chapman sweepstakes. Chapman’s payday? A six-year, $30.25 million deal. But three years later, Chapman is still not the starting pitcher many expected him to be. The Reds believe he will be down the road, that he’s a work in progress. Even though his performance as a closer earned him a spot on the All-Star team, he is still regarded as a pitcher whose promise remains mostly untapped.

Victim

Because of press deadlines, CityBeat doesn’t know how Chapman pitched in the All-Star Game July 10 in Kansas City. And unless someone tips us off, we won’t know if he was accompanied by the woman he was picking up at the Columbus airport on May 21 — whether or not she was the same woman he shared a hotel room with in Pittsburgh during a road trip on May 29.

The woman in Pittsburgh was Claudia Manrique, and for a couple of days she was quite the media sensation in the Steel City. Public records and news accounts depict her as a married, 25-year-old Colombian stripper living in Maryland where she was accused by an ex-boyfriend of stealing $2,000 from his bank account when he stepped away from his computer. The Baltimore County State Attorney’s Office, which filed, then withdrew grand theft charges against her, knows her as Claudia Manrique-Cediel.

Claudia Manrique-Cediel

As Homer Bailey was shutting out the Pirates on May 29, Manrique-Cediel was found bound by cloth napkins in Chapman’s hotel room at the Omni William Penn Hotel. She claimed she had been robbed by a fake hotel worker who wanted to get in to fix the toilet. According to the police report, when she let him in, he ordered her to give him a Louis Vuitton bag containing $200,000 worth of jewelry belonging to Chapman. How the man knew about the Louis Vuitton bag, she was at a loss to say.

Pittsburgh detectives took a crack at her the next day. This time, Manrique-Cediel claimed the man held a gun to her head, something she didn’t mention the night before. Her story changed from there. The fake hotel worker turned into a man who had stolen a wallet from her purse outside a nearby CVS store and threatened to harm her friend “Viviana” in Maryland if she didn’t let him in the hotel room.

“When we advised Manrique she was displaying numerous signs of untruthfulness, she became more nervous, and began crying,” Det. James Joyce wrote in his report. “It was obvious to us that she was lying about the robbery.”

It didn’t help that she failed a lie detector test. Manrique was charged with filing a false robbery report and is scheduled to appear in Allegheny County Municipal Court on Aug. 28. Even Chapman thought she was in on the “crime,” Joyce wrote. He thought it strange earlier in the day when she spoke English to a Spanish-speaking caller on the telephone. Chapman doesn’t understand English well.

Too bad Chapman didn’t know Shahryar Kamouei. The owner of a clothing store in Towson, Md., Kamouei played the Manrique boyfriend role several months before Chapman. Kamouei told CityBeat that he met Manrique when she was working at a strip club in Baltimore. He said he helped her upgrade jobs within the profession, first at the Ritz in Baltimore, then Camelot in Washington, D.C., where “she didn’t have to do rooms and dances.” He said she met Chapman at Camelot.

“I heard he went to Camelot a few times from talking to some of the other strippers who work there,” Kamouei said.

Kamouei and Manrique fell out over his claim that she transferred $2,000 from his online bank account in January. He filed the theft charge that the local prosecutor dropped last Friday. As for the incident in Pittsburgh, Kamouei said he has no doubt that his ex was part of the robbery. “She definitely did that there,” Kamouei said. “I’m 110 percent sure.”

Defendant

Now that he’s rich and living in America, Chapman is learning all about another facet of American life: lawsuits.

Eight months after defecting from Cuba, the first lawsuit landed in state court in Boston. A man who says he has known Chapman since the pitcher was 11, Carlos Thompson, claims that Chapman signed a contract promising him 3 percent of Chapman’s professional baseball earnings, 15 percent of any bonus payments and 3 percent of any marketing deals for seven years. That would give him a $2.5 million slice of Chapman’s compensation from the Reds. A judge dismissed the suit, ruling that Thompson didn’t have the required federal approval to cut a deal with a Cuban national. Thompson is appealing the ruling. Later in 2010, Thompson filed suit in Miami against Hendricks Sports Management, a Texas sports agency that represents Chapman. Thompson claimed that Hendricks stole Chapman from him. That suit was tossed as well.

Chapman’s name returned to the court docket again in May, this time in a Boston lawsuit depicting the harshness of Communist Cuba. Danilo Curbelo Garcia claims that Chapman and his father, Juan Alberto Chapman Benett, conspired with Cuba’s repressive State Security agency to stick Garcia with a false charge of trying to help Chapman escape from Cuba in 2008. The suit says Garcia was convicted and given a 10-year sentence, while Chapman regained favor with Cuban President Raul Castro after a failed defection attempt. Garcia wants $18 million. Chapman has until July 19 to file an answer.

Joe Kehoskie, a baseball agent who has represented about two dozen Cuban players, said lawsuits against Cubans who leave the island and get rich on baseball are fairly commonplace.

“These guys almost have a bull’s-eye on their back, especially when they’re in Miami,” Kehoskie said. “You’d think it’d be the opposite. I lived in Miami for years and I love Miami, but it may not be as welcoming to new Cubans as its reputation suggests. There’s a subcurrent in Miami where guys prey on guys like Chapman. They know he’s coming in from a system where he made $20 a month and lived in a crappy house and had to use a ration card to get his food to now where he has millions of dollars in the bank, or at least millions of dollars at his disposal, and everyone comes out of the woodwork to get him to invest, there’s a million get-rich-quick schemes.

“A guy like Chapman doesn’t have to earn another dollar in his life if he’s smart; he just has to sock away some of the money he has coming in,” Kehoskie said. “Every time these guys turn around, they’re getting ripped off. Kendrys Morales is a perfect example.”

Morales, the Los Angeles Angels’ designated hitter, defected from Cuba in 2004. He signed a six-year deal with the Angels for $4.5 million and joined the team in 2006. Last March, Morales’ agent, Rodney Fernandez, was charged in Florida with grand theft, allegedly taking $300,000 from Morales. Fernandez is currently awaiting trial.

As for Chapman, Kehoskie warns of another “bombshell” on the horizon.

“Reports have been mixed of whether he was actually married in Cuba, but he does have a daughter in Cuba and that’s been a cottage industry among Cubans as well,” he said. “I’m surprised someone hasn’t brought her out of Cuba so that she can get the 10 to 15 percent of his contract that she’d be entitled to whether they’re married or not. She’s entitled to a chunk for child support alone. It’s amazing the liabilities he’s facing, and he’s barely two years into his career.”

Alone

Even in a clubhouse filled with other Spanish-speaking players, like Johnny Cueto, Miguel Cairo and Wilson Valdez, Chapman drifts in and out of a parallel world. His manager, Dusty Baker, speaks Spanish, as does bullpen coach Juan “Porky” Lopez. Still, it’s hard for others to fathom what Chapman is going through.

“Sometimes you feel like — not depressed — but that you want to say something and you can’t say nothing,” said Brewers pitcher Livan Hernandez, who defected from Cuba in 1995 as a 20-year-old. “That was the hard part coming over here. Playing baseball wasn’t hard, because that’s what you’ve always done. The most important is the communication.”

Hernandez, now 37, learned English by talking to his teammates and has become one of the most respected players in the game by his peers. Hernandez said he has gotten to know Chapman, mainly because the two live in South Florida in the offseason.

“Trust me, you don’t have hard life here,” Hernandez said. “In Cuba, you have a hard life. Here it’s easy.”

But there is isolation. Before many games, Chapman sits alone in front of his locker, absorbed in his MacBook and Beats headphones. The language barrier can be a mixed blessing, discouraging approaches by people he would like to speak to and repelling those he cares not to.

“We don’t trust the media,” Hernandez said. “Sometimes you don’t understand and sometimes the media put something in the paper that he didn’t say, so that’s bad communication.”

Chapman didn’t speak to the media after his somersault celebration, in part because he was dressed down not only by Baker, but by teammates Votto and Bruce. The backlash might have caught him by surprise. In Cuba and other Latin American countries, baseball players are more demonstrative in their celebrations. There are celebrations for saves and bat flips after home runs, all accepted as part of the game. In the United States, such shows are considered boastful. Chapman’s off-mount gymnastics against the Brewers drew so much heat from his own teammates that the other team didn’t bother to retaliate. Had he not been so publicly rebuked by the Reds, it’s possible the Brewers would throw at the likes of Votto or Bruce.

Those kinds of lessons — how the game is played in the United States and the unwritten rules of being a big leaguer — are passed down from player to player as they move up the long ladder of the minor leagues to the majors. A typical player signed from the Dominican Republic could play at seven different levels before breaking into the big leagues. Chapman played only at the Triple-A level in the minors. Triple-A life is far from the glamor of the big leagues, but the occasional air travel spares players the frequent long bus trips and humdrum hotels of the lower minors.

“Normally with Latin players, you sign them at 16, and they come through your system,” Kehoskie said. “They might be coming from poverty or a background without a lot of education, but they learn things and in the progression from rookie league to A ball to Double-A, they learn a lot of things along the way. Guys from Cuba are coming from the same poverty, the same lack of education, but they’re skipping all those steps. One minute they’re in Cuba, the next they’re in the big leagues and they have millions of dollars at their disposal.”

Going forward

For now, Aroldis Chapman can lay claim to being a successful and All-Star closer. Some would say closing is where he belongs, entering games in the ninth inning, throwing 10 or 15 fastballs at 100 miles an hour and walking, not tumbling, off the mound. But as fans saw in June, those fastballs can become hittable. Whether or not Chapman was distracted by speeding problems, untrustworthy girlfriends or lawsuits, fans might never know.

The question is: do the Reds? The Reds refused to talk about Chapman’s off-field affairs or legal issues. General Manager Walt Jocketty and manager Dusty Baker said they would answer only baseball-related questions. If the team has any concerns about Chapman losing control of his Lamborghini at 95 miles an hour, it’s not sharing them with sportswriters. If the team has pulled Chapman aside to warn him of the pitfalls of befriending women with dubious motives, it’s not saying.

It was different with Josh Hamilton, the outfielder who spent 2007 with the Reds after — and while — battling drug and alcohol dependency. To keep him out of trouble, the Reds hired Johnny Narron, brother of then-manager Jerry Narron, to keep tabs on Hamilton day and night, even handling his money. Hamilton, though, requested the accompaniment. As a member of the payers union, Chapman cannot be assigned anyone to serve that purpose without his consent.

During media day in Kansas City on June 9, Chapman was again asked about the eventful two weeks in May, but once again interpreter Tomas Vera stopped the questioning short. When CityBeat explained it wanted to give Chapman a chance to give his side, to speak openly about what so many are whispering about behind his back, Chapman asked a simple question: Have you ever had a speeding ticket? How many? (The answer, by reporter C. Trent Rosecrans, was three, in 20-plus years of driving, though it probably isn’t of interest to anyone aside from the person asking it, if even him.)

Chapman then went on to answer other questions — from reporters all over the globe, in both English and Spanish. They wanted to know about his 105-mph fastball, his transition to closing, other recent Cuban defectors and his emergence as a superstar in a strange land.

For now, Chapman is an All-Star, a Cincinnati Red and the most exciting closer in the game. He will continue to draw a crowd based on his stunning physical skills, but questions about his life off-the-field life might only be answered with time.

This story first reported the model of Aroldis Chapman's Lamborghini to be a 2008 Diablo. It is in fact a 2010 Lamborghini Murcielago. This detail was incorrectly stated in a May 2011 Kentucky speeding ticket.

CONTACT JAMES MCNAIR OR C. TRENT ROSECRANS: [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected]