If you’ve been to the Cincinnati Art Museum recently, and specifically since March 22, you’ve probably found yourself lingering among portraits in a corner of the second floor. (Up the grand staircase and in Room 212, the space now designated as the museum’s photography gallery.)

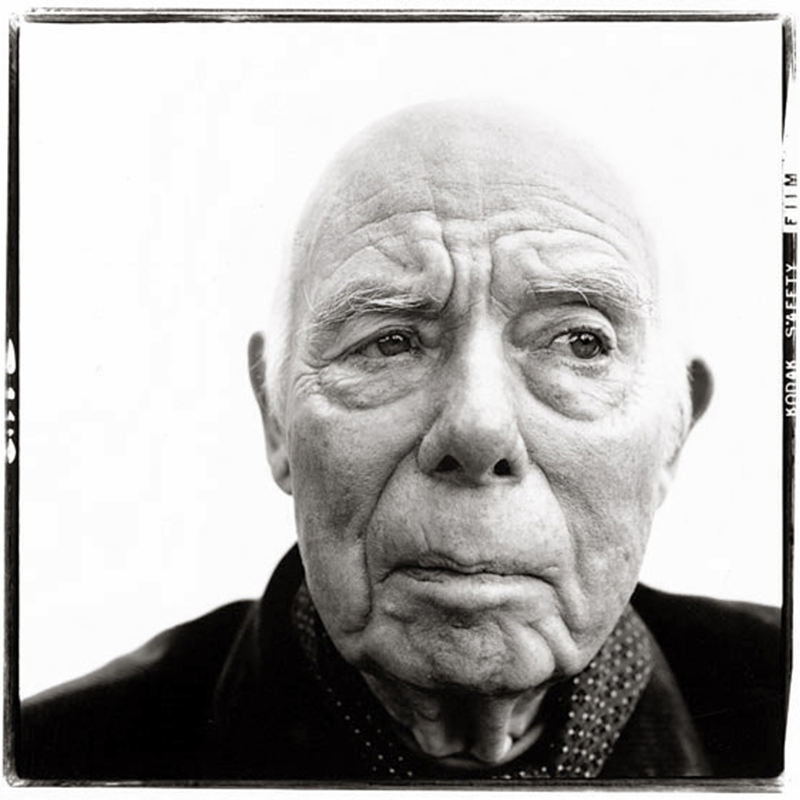

And it might’ve been Jean Renoir’s doing. The filmmaker’s honest, sideways smirk that’s good at whispering you in to laugh at life at or with him.

For me, he was the one whose 77-year-old face, through the gap of a narrow doorway, led me in to look upon his ruthlessness magnified, given new life by Richard Avedon and brought to light by Brian Sholis, the museum’s new curator of photography.

“It wasn’t until the 1970s when museums started taking photography seriously,” Sholis says. “The art world stopped writing it off as so mechanical and lacking real talent, so museums like this one began acquiring a lot of it.”

Which explains the 4,000-field, photographical rundown Sholis was sent before moving from New York to Cincinnati to take his curatorial position in 2013. The database was a list of every museum-owned piece of photography, and while studying it, Sholis noticed a pattern: two recognizable names in one row, repeated. An artist by an artist. Portraits of the Artist. You see where this is going.

“For people who don’t know much about the history of photography, they’re given another chance to connect here, and I wanted my first exhibition to be as welcoming as possible,” Sholis says. “Here, there’s twice the chance of hitting upon someone a visitor could recognize.”

Out of four-dozen artists-by-artists photographs, Sholis narrowed his exhibition selection to 14 of them, presenting Frida Kahlo by Bernard Silberstein, Picasso (with his son Claude) by Robert Capa and Miles Davis by Lee Friedlander, among others.

The dancer in me was especially drawn to modern mover Merce Cunningham by Barbara Morgan, who took Cunningham’s photo like he crafted his dances — with good faith in chance.

She shot the double-exposure by retrogressing her film after an initial shot and snapping Cunningham again in another position, not realizing the two bodies as one image until they’d been developed, much like Cunningham frequently rolled a die to dictate his movements and their sequences.

And while, like the individual pieces themselves, the idea of the exhibition is stimulating and timely (I don’t need to tell anyone about the portrait-in-the-form-of-iPhone-selfie phenomenon), the placement of the pieces is also noteworthy, and very thoroughly Sholis-thought-through.

The Mexican artist portraits are grouped together alongside a couple of painted face performers; partners in work and life, John Cage and Merce Cunningham share an intimate space on a portion of the gallery’s west wall; and Miles Davis is situated alone and dominantly, glaring over onlookers while avoiding awkward eye contact with Renoir (after being moved when Sholis saw the staring contest).

“These are more than just casual snapshots even though they look that way,” Sholis says. “These are kind of dialogues between the artists themselves and their creators, the photographers.”

And, of course, you.