In a Cincinnati neighborhood plagued by high rates of blight, poverty and crime, the new $18.4 million Robert A. Taft Information Technology High School in the West End couldn’t offer a more contrasting narrative. While city police book killers and other suspected felons right next door, Taft students are enriching their minds in nine computer labs and exploring the world through wall-to-wall Wi-Fi.

Behind the amenities is an even bigger claim to progress, an academic turnaround that has drawn attention from around the nation. Last year, every one of Taft’s 11th-graders had passed the state’s math and reading proficiency tests, a feat matched by only one other high school in all of Southwest Ohio. For two years now, Taft has racked up excellent ratings on its state report card. And in 2010, it softened the West End’s gritty image by winning a highly coveted National Blue Ribbon award from the U.S. Department of Education.

Like every public school in the nation, Taft High School is viewed through the prism of its numbers: the percentage that shows up for class; the percentage that graduates; the racial breakdown; the slice eligible for free lunches. And, perhaps more obsessed over than anything, academic test scores.

Numbers dictate the popularity of schools and the rise or fall of its administrators. Numbers, in Ohio, also dictate whether schools are “excellent,” “effective” or, as in Taft’s case in 2005, in an “academic emergency.” That year, Taft had an attendance rate, graduation rate and Ohio Graduation Test (OGT) passage rates that were best concealed from prospective parents. Only 40 percent of Taft 10th-graders passed the OGT math test, while 64 percent passed reading. To graduate, high school students in Ohio must pass all five OGT subject tests.

Miraculously, one year later, Taft High was shaping up as another Garfield High School, the troubled East Los Angeles school whose sudden prowess at math was depicted in the 1988 movie, Stand and Deliver. With a sharp focus on the OGT and with help from tutors from Cincinnati Bell, the same 10th-grade class that struggled with the OGT math and reading tests in 2004-05 was over the bar by rates of 95 and 97 percent, respectively, in 2005-06.

Ever since, the math and reading pass rates have stayed above 97 percent for Taft 11th-graders, culminating in the 100 percent smackdown in 2010-11. The only other high school in the region with perfect marks in both math and reading — Madeira High School — couldn’t be further removed from the poverty and high crime rate of Cincinnati’s West End.

As a reward for beating Ohio benchmarks on student test scores, attendance and graduation rates, Taft joined the likes of Walnut Hills, Sycamore, Indian Hill, Mason and the two Lakotas as excellent-rated public high schools.

Most people credit one man with making Taft what it is today — Anthony Smith, a Taft alumnus, former social worker and former science teacher who took over as principal in 2001. The man is a star in education circles, and last fall he was promoted to district assistant superintendent. Along with local coverage, Smith’s rehabilitation of Taft has been featured on CBS News, ABC News, National Public Radio, The Christian Science Monitor, Education Week and even a book titled “Inside School Turnarounds.” He has traveled extensively to share the Taft success story with other educators, including a trip to Harvard University in 2009. Because of Smith, Taft students are told, “failure is not an option.”

Why, then, does the heart-warming story of this inner-city-school-turned-academic-overachiever ring so hollow?

ACT scores below par

Two years ago, Cincinnati Public Schools wanted to find out how smart its students really were. Not by the low-bar OGT, but by the ACT, which measures not only what kids know but how prepared they are for college and careers. The district’s other excellent-rated school, Walnut Hills, posted an average combined score of 26 for the four-subject ACT (out of a possible 36), followed by Clark Montessori at 21 and the School for Creative & Performing Arts at 20. Taft got a 15. In spite of having joined Ohio’s postsecondary elite, Taft was not academically superior after all to other inner-city schools eating its OGT dust.

Aiken, Oyler, Western Hills Engineering, Withrow International and Woodward Career Tech matched Taft’s 15, while Hughes, Riverview East, Western Hills University and Withrow University scored higher.

The best that those nine schools could do on the state report cards in 2009-10 were “effective” ratings, at Aiken and Western Hills University. Hughes, Riverview East, Western Hills Engineering, Withrow International and Woodward were all on “academic watch.”

Taft’s second go-around with the ACT, in the spring of 2011, was no better. Its 66 test-takers, all juniors, averaged 15 as a group. Oyler and Western Hills Engineering, meanwhile, moved up to 16. In Kentucky, which requires all students to take the ACT, the average composite score statewide was 19 in 2010-11. There, Taft’s score was comparable to that of Covington Holmes High School, whose score of 16 was the lowest in Northern Kentucky.

Many colleges will accept students with such low ACT scores, but the better four-year colleges, such as the University of Cincinnati, generally draw the line at 21. “I believe the lowest score we took was a 17,” says Caroline Miller, UC’s senior associate vice president of enrollment management. “That person probably had very strong grades — or played the oboe well. Some good students just don’t take tests very well.”

How excellent can a school be with an average ACT score of 15? CPS officials, publicly at least, express no second thoughts about Taft’s excellent rating. They go strictly by the state report card and its reliance on OGT scores, attendance and graduation rates.

Smith, the former principal, said he wasn’t fazed by the low ACT scores, but made the point that students don’t try hard on a test that isn’t required for graduation. As for other mostly African-American schools outscoring Taft on the ACT, he says, “Some schools are actively moving along out there preparing kids for ACT and SAT. Guess what? You can mess up. So we did not want to be so cavalier saying we’re preparing kids for ACT and SAT. We prepare kids for OGT. We didn’t want to put the cart before the horse.”

Dr. Elizabeth Holtzapple, director of research and evaluation at CPS, said OGT scores are not necessarily a good predictor of how students will do on the ACT.

“They’re really only likely to do fairly well on the ACT if they scored in the accelerated or advanced level on the OGT,” Holtzapple says.

Yet 36 percent of Taft’s sophomores in 2009-10 — the same group of students who averaged a 15 on the ACT in 2010-11 — scored in the “accelerated” or “advanced” ranges on the OGT. Only 19 percent of students at both Oyler and Western Hills Engineering did as well.

Holtzapple backtracked and said Taft focuses on the OGT; Taft’s low average ACT score takes away nothing from its excellent rating. “Myself and the district are very proud of what has happened at Taft High School,” she says.

Other educators, however, say that the low ACT scores expose flaws in the state’s school-rating system and raises doubts about the fitness of Taft graduates beyond high school.

Michael DiSalvo, owner of A+ Tutoring/Test Preparation in Springdale, said Taft students aren’t learning what they should be learning in high school.

“(Taft’s ACT score) shows a lack of deep knowledge of those subjects and a lack of critical thinking skills,” DiSalvo says. “They can get by with some basic level of English and reading, but as far as knowing things deeply and being able to analyze things, they either haven’t been taught that or they haven’t learned that.”

Mark Hartman, a senior director at the Battelle for Kids Institute in Columbus, said the ACT reveals one’s readiness for work as well as for college.

“You need to be either college ready, career ready or work ready, and really what that means is, when you go into the workplace you are trainable — that is, you have literacy and numeracy so I can train you to do your job,” says Hartman, a former principal at Glenoak High School in Canton. “Really, what the ACT determines is that you have a set of skills so you can, one, take a college class or, two, be trainable in the workforce.”

Ann Sheldon, executive director of the Ohio Association for Gifted Children, took one look at Taft’s juxtaposed OGT pass rate and average ACT score and exclaimed, “Holy crap! We’re just pretending here.”

In November, Sheldon’s group issued an eye-opening report showing how cheap “excellence” has become in Ohio public school districts the last eight years. Taft’s ACT scores, she says, expose the school’s shortcomings in preparing students for adulthood.

“Why is there such a large gap between what we feel is excellence in Ohio versus what the education testing companies nationally are saying are required for college and career?” Sheldon asks. “Are we lying to these kids and their parents about how prepared they are? What are the implications of that?”

‘This doesn’t look right’

Some of Taft’s own teachers have wondered the same thing. From 2005, as Taft’s state rating climbed to the top, those teachers shook their heads upon hearing that first 90, then 95, then 100 percent of their students were passing the five OGT subject tests — math, reading, writing, science and social studies.

CityBeat spoke with five current and former teachers who worked at Taft under Smith. None wanted to be identified in this article, fearing negative repercussions for their careers. All five said Taft’s OGT pass rates were not believable.

“My first reaction was, ‘Oh, look at this. This is really good. I must be a good teacher,’ ” one teacher says. “But 15 or 20 seconds later, I said this doesn’t look right. This student never comes to class and that student never comes to school, and yet they passed.”

Says another, “On any given day in that time period, a third of my students would not have been present, and among the kids that showed up, 25 percent — conservatively — were failing.”

Roughly a fourth of Taft’s population consists of special-needs students with one type of disability or another, mostly cognitive-related. They, too, are required to pass the OGT subject tests, and, according to data reported to the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), passing they are.

“It’s just funny to hear that these kids that are cognitively delayed with a fourth- or fifth-grade reading level are passing a test that requires them to read through a reading selection and respond to questions,” says a third teacher. “I see the results of basic tests and reading assignments in the classroom, and there’s no way these students are passing all five parts of the OGT. They would literally have to have someone change the answers or give them the answers.”

Most students, this teacher adds, are thrilled to learn they had passed the OGT. Others, though, confided that they couldn’t have: “I’ve had plenty of kids come to me and say they didn’t believe they passed it or that it was too hard and they skipped a lot of answers.”

Teachers weren’t the only people who smelled something foul. After the spring 2006 OGT test that propelled Taft up the excellence ladder, ODE received word from its outside test contractor of “possible security violations/testing irregularities.”

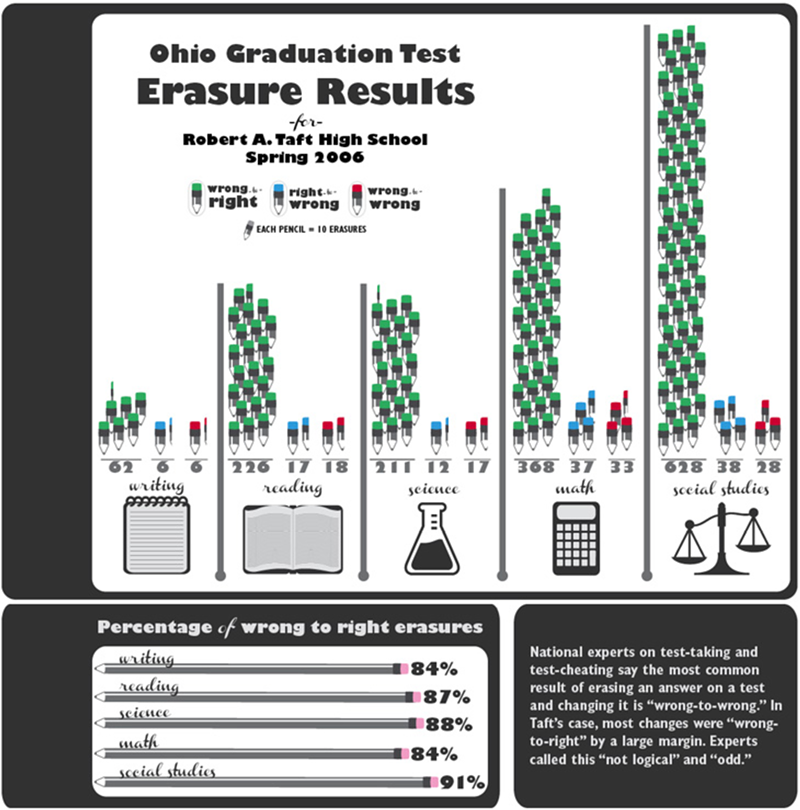

What the testing contractor found was alarming: Of 1,707 instances where students had erased one multiple-choice answer in favor of another, 88 percent resulted in correct responses. The remaining 12 percent of erasures went from right-to-wrong or wrong-to-wrong.

Of the 26 erasures on social studies question No. 26, every one resulted in a correct answer.

Looking at individual students’ answer sheets, the test contractor found 116 with numerous erasures leading to correct answers, including 15 where every single erasure-change hit the mark.

One 10th-grader was 18 for 18 on the social studies test. An 11th-grader was 15 for 15.

All names were removed from the erasure analysis provided by CPS.

None of this would become public for five months. CPS wrote to ODE in June 2006 seeking to “review the (answer) documents to determine if the erasures were made by the students taking the test or by a possible second party.”

ODE’s test security rules, however, required CPS representatives to review the documents in Columbus in-person and forbade them from copying the answer forms or taking notes, Holtzapple says. CPS balked at such restrictive conditions. Unable to review and mark on answer forms to “identify if the violations appear to by (sic) students or adults,” CPS, then led by Superintendent Rosa Blackwell, closed the investigation on June 22, according to a letter to ODE from CPS general counsel Cynthia Dillon.

The district never got around to interviewing students or the Taft teachers and administrators who proctored and collected the tests.

“We didn’t understand how we could get the information we needed if we were not allowed to make any notes,” Holtzapple says. “I would think that if the district is trying to do due diligence that they (ODE) would cooperate in allowing the district to review the answer documents and make notes.”

Five years after the episode, ODE isn’t sure what happened. Its point person on the matter, former assessment director Judy Feil, left ODE and is now deceased. But it is ODE’s — not the district’s — call to end an investigation, and as far as anyone at ODE knows, says spokesman Patrick Gallaway, “the matter was not closed.”

For all the school district’s insistence on conducting an investigation on its own terms, both Holtzapple and Smith say they saw nothing unusual about the 88 percent correction rate on erased answers.

“What they’ve done is they’ve indicated that they’re not sure between two answers, and they can go back and look at it again and are able to eliminate the wrong answer,” Holtzapple says.

Smith offers a more elaborate explanation. He said Taft students were — and still are — taught to fill in two answers when they’re not sure.

“We did an analysis of test-taking strategies and realized that if the student does not understand the answer for, let’s say number one, he skips number one and he believes that he’s answering the question to number two, but it very well may be number three,” Smith says.

“Having two answers bubbled in lightly, not dark because it may not clear up, gives you more of a placeholder of where you are on the test as opposed to ‘Am I going to get the answer right or not.’ It gives you a reason to go back and say, ‘Wait a minute. On this line I have two answers bubbled in. I know I have to get rid of one,’ and hopefully you went back and found the results or found the answer that was more comparable to answering the question correctly,” he adds.

As for how students managed to divine the answer on seven of every eight such dilemmas, Smith saw nothing out of the ordinary.

“Absolutely not,” Smith says. “When you look at the process we put in place about preparing kids for the OGT and preparing kids for test-taking strategies, no, I didn’t think it was unusual.”

Erasures prompt doubts

CityBeat decided to show the Taft erasure analysis to two independent test experts.

John Fremer, president of Caveon Test Security, a Utah company that did a forensic analysis on the widespread test erasures in 58 Atlanta schools in 2010, was astounded by what he saw.

“Once students change answers, there is a slight tendency for them to improve their overall score. They simply don’t change all or almost all of their answers from wrong to right. It’s hard to imagine a legitimate educational setting where that happens,” Fremer says. “If you create a record of students making changes, the mostly common result is wrong to wrong.”

Erasures resulting in correct answers 88 percent of the time, he adds, is “not logical.”

Another nationally known expert on test cheating, Jim Wollack, director of University of Wisconsin Testing & Evaluation Services, says the Taft situation struck him as “odd.”

“Students tend not to erase on a test. It’s on the order of one or two on average, and when we do see erasures, we sort of assume there’ll be wrong-to-rights, wrong-to-wrongs and right-to-wrongs, maybe not in even percentages,” Wollack says. “Here you see not just the high number of erasures, but a high percentage of erasures that are wrong-to-right, and the fact that they’re concentrated in one school is also suspicious.”

News of the erasures investigation finally made the news in October 2006 — for a few milliseconds. The Columbus Dispatch made the initial, brief mention of it in a broader article on the subject of cheating.

That, in turn, caught the eye of several Cincinnati Board of Education members, who weren’t aware of the investigation until their Nov. 6 meeting. They wrote a letter to ODE asking to reopen the case, but nothing came of it. Same with Smith’s offer to have Taft students retake the OGT. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported on the board discussion, but wrote nothing further.

Not once in the five years since has Taft High School been the subject of another erasure investigation. Fremer, whose company also offers cheating-prevention services, was surprised the 2006 investigation died.

“There should have been a conscientious examination of what happened, at least a determination that they needed to improve their procedures,” Fremer says. “When nothing is done, it may simply continue, and your year-to-year comparisons are consistent.”

And how have Taft students done after graduation? Smith said he didn’t know how many went to college, but that those who did have received waivers of entry-level courses.

“If you go back and look at some documentation on kids entering universities, many of the Taft kids actually tested out of basic 101 courses, and so they didn’t have to take maybe the freshman English course or the freshman science course,” he says.

Ohio Board of Regents data suggests otherwise.

In a report covering the class of 2009, the agency found that 15 of the 16 Taft students who went to a state university or community college needed to take a remedial math or English course as freshmen, or 94 percent.

By comparison, the corresponding number at Hughes was 58 percent (of 53 students), and 52 percent at Western Hills Engineering (of 25).

Smith’s “documentation,” he concedes, was purely anecdotal, as told to him by students.

“I don’t see any reason that they would not tell the truth about it,” Smith says. “These are things that they were giving me.”

It is this apparent lack of preparation for college — and for life in general — that concerns the teachers interviewed by CityBeat. Filling students’ heads with an inflated notion of excellence and helping them pass one test — especially if they didn’t — can set them up for undeserved disappointment, they say.

“On one hand, I don’t want any negative tarnish on Taft, but what kind of service are you doing for the students if you’re just passing them along?” asks one teacher.

“We are, in essence, doing the individual student an injustice because we are giving them the belief that they’re legitimately passing these tests,” says another. “It heightens their confidence and falsifies the fact that the education is better than it is, and when they go out and face situations and adversity, they won’t have the tools. It just makes the institution look good.” ©