Olivia Harper was here when workers tore a yawning gulch through Walnut Hills. It ran up to her mother’s door before swallowing her house whole, making way for a wave of concrete that still runs through the neighborhood.

The highway, I-71, claimed her sister’s house, too, some 45 years ago. In its wake, Harper saw the neighborhood where she grew up, taught school, did business and made memories continue to wilt. She stayed anyway.

Now, as redevelopment accelerates in Walnut Hills , Harper fears she may have to leave just as things are picking up again.

Some of her neighbors, also black and low-income for the most part, have already had to move away from one of Cincinnati’s most historic and diverse neighborhoods. Still more face uncertainty.

They represent one portion of the neighborhood’s 6,500 residents, but they reveal a difficult flipside to one of Cincinnati’s most celebrated examples of urban renaissance.

Braving the December cold, Harper walks across the thin winter grass spanning the front yard of her house and three identical tan townhouses on Kenton Street to deliver a big box of diapers to her neighbor’s new baby two houses down.

There, the thudding and banging of roofers on top of Sheron Kidd’s house is keeping her 10-day-old great granddaughter from sleeping.

Despite the noise, Kidd’s house is otherwise comfortable, the walls decorated with paintings and photographs. Kidd, who has lived here for the past six years with her granddaughter, sits on a cushy couch and talks over the noise about her pending move.

“I’ve felt so helpless,” she says of the month she’s spent looking for housing since receiving notice from the townhome’s new owner, Moayed Harb, that she will have to move out. “I can’t sleep at night, thinking, ‘What if I don’t find anything tomorrow, and I can’t find anything the next day?’ You talk to people, and stuff’s already rented, or it’s like, $900 a month. We’re packing up, wondering where we’re going to go.”

Residents at the Kenton Street townhomes found a letter in their mailbox in mid-November informing them of the sale of the property and giving them until the end of December to move. They pushed back, organized by the Greater Cincinnati Coalition for the Homeless, and, after some pressure, Harb moved the date back a month.

The weeks after that letter have been a flurry of searching for apartments. After finding little in Walnut Hills that meets their budgets, both Kidd and Harper say they have taken to looking at places in Carthage, at the edge of the city, or Cumminsville, an isolated, low-income neighborhood tucked away in the Mill Creek Valley.

“It’s causing me to see the plight of African Americans in Cincinnati, period,” Harper says. “The places we’re being channeled into are places you would never want to live.”

Some see these moves as an unfortunate, but necessary, inconvenience for long-term residents. But Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove, a professor of clinical psychiatry and public health at New York’s Columbia University who has studied the effects of displacement for decades, says such moves can be incredibly traumatic, life-changing events.

“The losses that people suffer when they lose their neighborhood are losses of entire worlds,” she says. “It’s lifelong grief. When you’re forced to leave your neighborhood, you’re forced to leave your fundamental social, economic and emotional networks. And to rupture those is devastating.”

Big Gains — at a Cost

It’s no secret Walnut Hills is experiencing a burst of activity, with new restaurants, bars, breweries and market-rate housing coming at an ever-accelerating clip to areas that have seen decades of disinvestment.

A quick trip down McMillan Street, just blocks away from Kidd and Harper’s homes, reveals the changes happening. Some buildings near the once-bustling business district are low-key — older, a little scruffy, but still buzzing with the lives of their inhabitants. Those often stand next to buildings that are mere shells, voids of vacant windows staring out onto the street. And, increasingly, others nearby are undergoing or have recently received renovation.

The farther east you go, the more of the latter you’ll see. On one block of McMillan across Gilbert Avenue, movie titles line the shallow shelves of a video rental storefront that conceals a popular bar. Nearby, the silvery windows of MORTAR, a minority-focused startup incubator, gleam in the sun. Those fronts, and others, are part of Trevarren Flats, a $10 million mixed-use historic rehab helmed by the Walnut Hills Redevelopment Foundation. The development’s six studios and 24 two-bedroom units run from $925-$1,450 a month.

In keeping with an effort to reflect the neighborhood, at least racially, some of those new businesses are minority owned. Esoteric Brewing, the city’s first minority-owned brewery, is soon to come to the neighborhood’s iconic Paramount Building at the prominent corner of McMillan and Gilbert avenues. That redevelopment project will also have a mixed-income housing component. Just down the street, black-owned Just Q’in serves up barbecue.

The WHRF has facilitated many of the neighborhood’s new developments. It’s a different organization than the one that the neighborhood council created in 1977 to further affordable housing and the one that built the townhomes on Kenton Street in 1992.

Six years ago, the organization underwent a reboot, refocusing its mission on cultivating public-private partnerships, efforts to activate urban spaces in the neighborhood and attempts to draw in new residents and businesses. By those measures, it’s made big progress toward its goals.

But that growth has downsides.

Just a few blocks from the Kenton Street townhouses at a pizza restaurant in a historic firehouse that WHRF played a part in rehabbing, the organization’s Executive Director Kevin Wright talks about the role the foundation has played in the neighborhood.

“When you look at the big picture for the redevelopment foundation, the last five or six years have been about building an excitement and a market and bringing people back in,” he says. “We really feel like we’ve achieved that, so we’re shifting to put more focus on making sure that the market we’ve helped create helps people in the community, provides affordable housing and jobs.”

Wright calls the plight of residents like Harper and Kidd “terrible.” But he says he believes that doing development equitably is still an attainable, if complex, goal.

Some place part of the blame for the plight of residents like Kidd and Harper at the feet of the redevelopment foundation itself for its role in the millions of dollars in new projects coming to the neighborhood. Others applaud the rehabilitation of the neighborhood’s crumbling housing and commercial buildings, and say the community’s economic prospects are buttressed, not hurt, by the foundation’s efforts.

One thing those on various sides of the debate could probably agree on: addressing the Pandora’s box of forces that renewed interest in a neighborhood unleashes is likely beyond the reach of an organization like WHRF alone.

Independent property owners who offer low rents or subsidized units have started selling as Walnut Hills heats up. That can leave low-income renters in a tough spot, especially those like Kidd and Harper who do not receive government rental assistance.

Investment — and Sometimes Displacement

Harper says she moved into her townhome in 1992 on the premise that the affordable housing was part of a rent-to-own program. But that never came to fruition. She’s been the only tenant to ever live in her unit through all of its owners.

CityBeat wrote about Harper in 2016, when she attended public input meetings by the WHRF around development happening in the neighborhood. That public engagement effort led to the development of the Walnut Hills Reinvestment Plan.

“Walnut Hills is changing,” the preamble to the 2016 plan reads. “Our community’s long time residents and businesses are welcoming new investment into the neighborhood for the first time in years. Our trajectory is set to return Walnut Hills to Cincinnati’s ‘second downtown’ that it once was. But we need to make sure we get there with our existing community fabric intact and leading the charge.”

Despite the efforts, Harper, Kidd and others in the townhomes face a tough fate: be out by Jan. 31 or face physical eviction.

The row of four houses where Kidd and Harper live, along with two others across the street, were constructed 25 years ago by the WHRF as affordable housing. They’ve changed hands a number of times since then. The row where Kidd and Harper live was most recently sold in November for $57,500 a house.

“Join the Walnut Hills renaissance and invest in these rental units,” reads an old online ad for the buildings previously owned by Ed Horgan, who holds a number of properties in the neighborhood. “Long term leases have converted to month to month.”

New owner Harb says he bought them as investment properties and is weighing what he’ll do with them. That could include selling them or living in one and renting out the others.

But Harb says he wants to rehab them first, and that means Harper, Kidd and her neighbors have to go. In the meantime, the roofers work above their heads, readying the houses for their next occupants.

Residents at the townhomes say Harb has been rude and threatening. One letter from the landlord tells residents not to call him, but to correspond only through notes left in the townhomes’ mailboxes.

Harb offered as much as $500 if the residents moved out early, though the amount diminished the closer it got to the move out date. He says he feels for them, but that he’s simply doing what he’s legally entitled to do as the property’s owner.

“Isn’t it a good thing that we’re trying to improve neighborhoods?” he asks. “Someone who works hard and gets a mortgage and wants to do something gets called heartless, like, ‘you’re kicking them out on Christmas.’ Don’t be a victim. Take the positive side of things and move on.”

Kidd and Harper aren’t the only ones in this situation. Another buyer purchased one of the townhomes across Kenton, and its former residents have already left Walnut Hills. A couple blocks away, on Wayne Street, other residents have also recently left the neighborhood.

Changing Kenton Street

On an unseasonably warm day early in December, three women were hanging out on the steps of a building at the corner of Wayne and Kenton streets, where one of them lives for at least a little longer. It’s subsidized housing owned by local developer Model Group, and the women are poring over a letter the residents of the building received saying they will soon have to move and detailing an offer for relocation expenses.

The two buildings, which Model bought last year in a deteriorated state, are coming down to make way for Firehouse Row, a mixed-use development by Indianapolis-based Milhaus and facilitated in part by the WHRF. The project features 4,500 feet of retail space and 124 units of higher-end market-rate housing.

WHRF’s Wright says that housing subsidies from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development associated with the Wayne Street properties will go to a new Model Group project called Scholar House, a $12 million, 45-unit apartment complex that will provide affordable housing for low-income single parents pursuing post-secondary education.

“I think the Wayne Street issue is reflective of how complex this whole thing is,” Wright says. “We’re tearing down a building that’s affordable and moving people out of it and building a building that is high end — on the surface level it’s like, ‘that’s awful.’ But on a deeper level, what’s happening is, those contracts are helping make Scholar House happen. On the one hand, I think it’s hard to argue that taking those units of the distressed building and making Scholar House is bad. But at the same time, people are being moved out. I’m not going to sit here and say that’s a good thing. On any level, people losing their homes is bad.”

Model says it has secured housing in Walnut Hills for the four families living in the two buildings. But others haven’t been so lucky.

One of the other women gathered on the steps at the apartment building lived down the street until recently, when the property containing her apartment was sold. She was back in the neighborhood to visit.

“They’re just wiping us out,” she said, giving her name but asking not to be identified in print. “They’re trying to push us out to the suburbs where we don’t want to go.”

Charmaine Robinson, the third woman, is also back in the neighborhood to visit. She lived on Wayne Street before the house she was renting was sold earlier this year. She says she was offered the opportunity to buy the property, but its cost and condition didn’t work for her.

She now lives off of Springfield Pike in the suburbs north of Cincinnati. Robinson is philosophical about the move. She says she likes her new neighborhood but misses Walnut Hills. She also notes that some others from the neighborhood in similar positions — including a friend who lived in a now-sold townhome across the street from Kidds’ — were not at all happy that they had to leave.

Other buildings are also on the market.

The property across Wayne Street from the Model properties — built by the WHRF in 1992 as affordable housing for seniors, but no longer owned by the foundation — is for sale for $595,000. One page of a lengthy packet advertising the property details the rents currently charged in the building — between $400 and $500 a month. Another page lists a number of nearby buildings where rents are double or more than those amounts.

Sometimes Troubled, Always Home

Kidd’s parents lived on Kenton Street for 15 years before she was born and several years afterward. She can tell you in detail about the warm summer days she spent as a preteen picking pears in her neighbor Eddie’s yard, who, all these years later, still lives on nearby May Street.

“I’ve always told people I was born in Walnut Hills,” she says. “It’s always been in me.”

She doesn’t idealize the neighborhood, and neither does Harper. Both say this part of Walnut Hills was once called “the Wild, Wild West” for crime and “house joints,” or underground bars run out of single-family homes.

That’s a reputation that continues here. Last year, Kenton Street saw the shooting death of Jamie Urton, which happened March 24 after a young child ran out in front of Urton’s car as he drove down Kenton. Urton hit the child. When he left his car to check on the boy, he was shot and killed. The incident made local headlines for days.

But like the problems facing it, Walnut Hills itself is complex, and there’s more to the story than crime.

Even into the 1930s, Walnut Hills had a large middle class that was both black and white. But a succession of blows hit the neighborhood hard.

Redlining, or lending practices by banks that shun minority neighborhoods based on maps drawn by the federal government in the 1930s, made it hard for businesses and homeowners to invest in Walnut Hills and other black enclaves in Cincinnati.

The practice, illegal today, still hangs around. Two local banks, Union Savings Bank and Guardian Savings Bank, were sued by the federal government in 2016 for discriminatory loan practices in majority-black Cincinnati neighborhoods like Walnut Hills.

Battered by disinvestment and frustrations that exploded into civil unrest, Walnut Hills found itself a prime example of white flight in the 1950s and 1960s. The white population went from a slight majority in 1950 to about 20 percent today.

Harper has lived in Walnut Hills since her birth in 1947, growing up on Foraker Avenue in the northwestern part of the neighborhood and attending — and later teaching at — Douglass Elementary School, which still exists.

She remembers the colorful signs of black-owned mom-and-pop stores that lined Gilbert Avenue and other thoroughfares — laundromats, grocery stores, daycare centers, mechanics, barbershops.

By the time I-71 came through Walnut Hills in the 1970s, disinvestment and blight had already begun and its white population was already streaming out. The highway, destroying homes, churches, businesses and schools, was insult to the slow-burning injury.

The painful memories of neighborhoods cleared out for highways make new development rolling through all the more difficult to see, Columbia University’s Fullilove says.

“These neighborhoods were highly organized and functional,” she says of black communities disrupted by highway construction. “And they were never rebuilt. This is a catastrophe for the individual, especially people who were teens to adults. They’re very aware of the loss.”

Economic Lift, Demographic Shifts

The neighborhood has yet to fully recover from decades of economic segregation and neglect. Some say organizations like WHRF can help heal those scars; others say they risk inflaming them again.

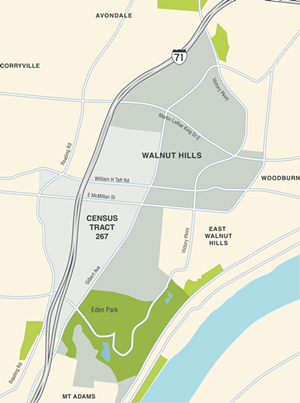

Nestled just next to the highway, Census tract 267 incorporates the area around Kenton Street, sometimes known as the “southwest quadrant” in Walnut Hills.

The tract’s 1,600 residents are roughly 85 percent black. Nearly half live below the poverty line. The median household income in 2016 was estimated to be $16,659. That’s less than half the city’s median household income of about $35,000 a year, but up about $1,000 from 2010.

The median rent in Harper and Kidd’s sector of Walnut Hills rose over 20 percent in the last six years, according to a review of successive years of the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

At the same time, the percentage of renters paying more than 50 percent of their income in rent — well above the federal government’s guidelines for affordable housing — went from 28 percent to 35 percent, according to that data.

The tract lost 10 percent of its 1,449 black residents between 2011 and 2016, according to the ACS. In the same time frame, the neighborhood’s white population tripled, according to the data. While those loses and gains are within the margin of error for the ACS on any given year, data show this reduction in black population and increase in white population intensifying each year, suggesting a trend.

People move out of a neighborhood for a host of reasons, and it’s not possible to say how many left Walnut Hills due to a lack of affordable housing. But it’s one very plausible factor.

The Future of Affordability

Like many urban areas, the Cincinnati region is seeing a squeeze when it comes to housing affordability. The well-publicized gap stands at 40,000 units of housing needed to meet demand from Hamilton County’s lowest income renters, according to a study done by LISC (Local Initiatives Support Corporation) last year. The wait list for Section 8 vouchers or Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority units can be years long, and few other options are readily available.

The city’s affordable housing shortage hits neighborhoods like Walnut Hills hard.

Currently, there are 1,103 subsidized units in Walnut Hills — about a quarter of all housing units in the neighborhood. Most are occupied, and almost all are spread out among 15 aging, distressed apartment buildings like Alms Hill, which looms over Victory Parkway on the eastern end of the neighborhood. After years of not investing in the building and other affordable housing across the city, New Jersey-based owners PF Holdings saw the city of Cincinnati strip them of control of the properties and place them in receivership.

The Alms was once a grand hotel that hosted galas for the city’s black elite. Now it and its hundred-plus units of HUD-subsidized housing hang in the balance, awaiting a buyer that will preserve it as affordable housing. Or, perhaps, turn it into something else entirely.

WHRF’s Wright says the redevelopment foundation is shifting to focus on preserving and building affordable and so-called “workforce” housing for low and moderate-income people in Walnut Hills.

By Wright’s count, Walnut Hills has 91 new affordable units recently completed or in the development pipeline. That’s 26 percent of the 350 new units recently built or coming to the neighborhood. Most of those affordable units are accessible to families making 45 percent of the area median income level or lower, Wright says. That income equates to about $33,000 for a family of four.

Wright cites recent city moves putting a few million dollars into affordable housing, as well as long-term proposals by Mayor John Cranley, as steps in the right direction. But he says more needs to be done.

“We’re not doing enough,” Wright says. “But we can’t solve the problem on our own. We need help. We need the city to help. We need these larger institutions to help. People need to understand that there are real victims of growth. But there are also real solutions to making sure that growth is inclusive. We need policy and we need more money.”

That conversation is happening at City Hall. Mayor Cranley has proposed using a process called voluntary tax incentive contribution agreements, or VTICA, to generate more funding for affordable housing over time. VTICA is already used in Over-the-Rhine and downtown to fund streetcar operation. Cranley said it could also be harnessed for an affordable housing fund in other areas.

Others want to move faster. On Jan. 18, Cincinnati City Councilman David Mann introduced a motion asking the city administration to find more immediate solutions. Six other council members — Jeff Pastor, Tamaya Dennard, Chris Seelbach, P.G. Sittenfeld, Wendell Young and Greg Landsman — signed on to that motion. Mann applauded Cranley's VTICA proposal in the letter, but wrote that it will take years for developers to generate the contributions necessary to fund housing. Mann also wrote that he believes VTICA can't meet the whole need by itself, and that other solutions will be necessary.

In the meantime, residents like Harper wait. In late January, she found a smaller, temporary place in the neighborhood, but says she’ll need to find housing again soon. She returned to her old home on Kenton Street to grab a few last things and found a three-day eviction notice on her door, she says. Her neighbors in the other townhomes, including Kidd, are moving out of Walnut Hills to places like Price Hill, Mt. Airy and Northern Kentucky.

Much of the Walnut Hills that Harper loves exists only in memory. She’s desperately clinging to what’s left, she says, but fears she may end up exiled from even that as forces beyond her control compel her to move.

“This is just the second phase of being displaced for me,” she says. “I know time changes things, things have to improve. But they should improve for everyone.”

Correction: due to a typo, the original version of this article misstated Walnut Hills' population.