Robert Goering is one of Hamilton County’s most essential governmental executives. As treasurer, he serves as the county’s chief tax collector, making sure that citizens pay for services like schools and police protection. He is also the county’s chief investment officer, responsible for generating returns on public money while keeping it safe.

In most Ohio counties, such crucial duties constitute a full-time job. Not in Hamilton County. Somehow, over his 25 years as treasurer, Goering has managed to find the time to run a very busy bankruptcy law practice in Cincinnati. He also represents private clients in foreclosure cases and financial disputes in state court.

How does Goering pack two full-time occupations into a 40-hour work week? He’s not telling. Nothing requires him to report how much time he spends clocked in at the treasurer’s office, away from the Goering & Goering digs on Third Street. His critics — all Democrats — accuse him of being chronically AWOL from the job he was elected to perform.

“It’s one of the county’s worst-kept secrets,” says Seth Walsh, the latest in a long line of Democratic treasurer-seekers. “Everyone knows about it and talks about it, yet people in power allow it to happen.”

Actually, state law does not prevent Goering from moonlighting, just as it allowed county prosecutor Joe Deters to rack up $2 million from outside work during the last eight years. But while Deters takes a 30 percent pay cut for being part time, Goering is subject to no such lower pay rate. His yearly salary is $76,959, regardless of his face time in county hall. He does not disclose, in his annual reports to the Ohio Ethics Commission, how much he makes on the side.

Goering’s connection to the treasurer’s office dates back to his teenage years. Wayne Wilke was the treasurer, and Rob, as he is known, opened mail. From there, he climbed the ranks to work “almost every position” in the office until his political appointment to the top spot in 1991, according to his campaign site. Election challengers since then have all fallen short, leaving Goering in what might come across as a lifetime appointment.

For someone who has held elected office since the birth of the World Wide Web, Goering is as low-profile as they come. His public persona is certainly far below that of, say, Deters or county auditor Dusty Rhodes. CityBeat could not find any in-depth profiles of Goering, Facebook or Twitter accounts or even press releases from his county office.

The media insularity shows. Responding to CityBeat’s emailed request for an interview Sept. 14, Goering replied that he would be “happy” to call. Within three hours, he had a 180-degree change of heart and decreed, “You must use the below as my response, verbatim.”

Troubled by the tax man’s imperative tone, CityBeat obliged.

“I decline the request of CityBeat and James McNair for comment on any issues,” Goering wrote. “This is because of the recent articles, which I would label hatchet jobs and slanderous, on my attorney the Hamilton County prosecutor. It is not journalistic and is totally inappropriate that personal and family attacks were made by CityBeat and James McNair.”

Because public officials will often relent to persistence, CityBeat sent Goering several specific questions. Among them:

• How many hours per week do you typically work in the treasurer’s office versus your personal law office?

• How do you manage the time requirements of a high-ranking county executive and a private attorney with a robust practice?

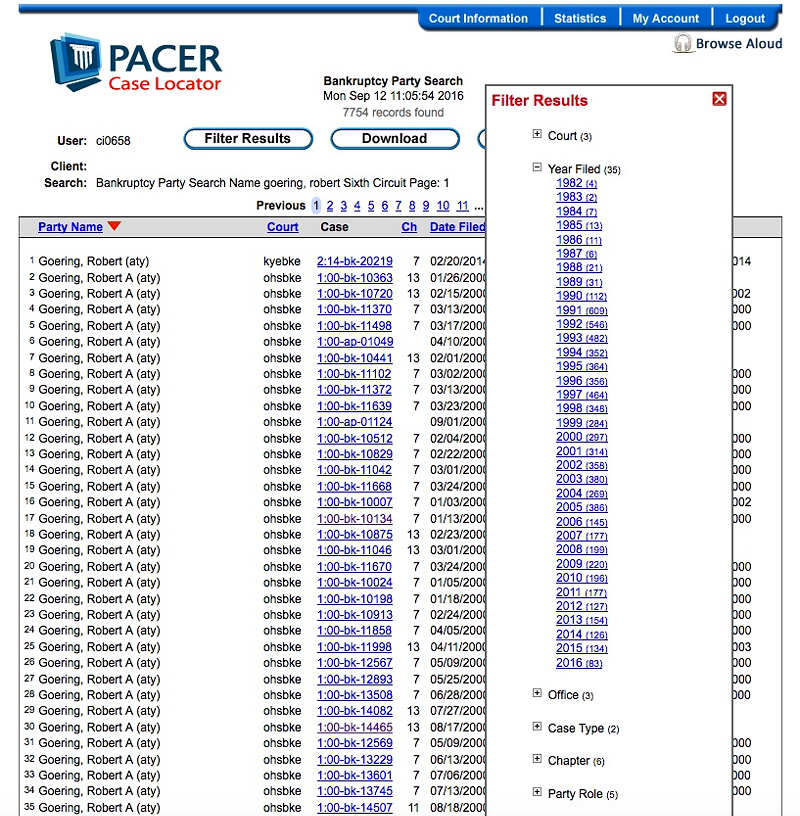

Goering did not respond. CityBeat asked these questions because the federal court document filing system shows Goering as the listed attorney for more than 7,300 bankruptcy filings and appeals in Ohio and Kentucky since 1991, or nearly 300 per year, after filtering out hits for his father and law firm colleague Robert Goering Sr.

Jeff Cramerding, who ran unsuccessfully for treasurer in 2012, says it was difficult to make voters aware of Goering’s sporadic service to the county. Walsh, the 2016 opponent, is again pounding home the point, hoping that even Republicans will be outraged.

“I don’t see how you can be a committed county executive and manage a law practice of that magnitude. He’s also a professor at NKU (Northern Kentucky University),” Walsh says. “I can’t imagine there’s much time left for him to be truly dedicated to running the county treasurer’s office. His energy is clearly not going into being treasurer.”

David Pepper worked with Goering as a county commissioner from 2006 to 2010. Now chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party, he says Goering has time to spare because he doesn’t fully exploit the powers of the treasurer’s office for economic development purposes, as treasurers do in other counties.

“The part-time nature of what he does speaks to the narrow vision he has for the office,” Pepper says. “He’s a small-C conservative and doesn’t think the office should do much more than its basic role. … If he had a full-fledged view of what the treasurer’s office should be doing, that would create problems for all the other work he’s doing.”

The nature of Goering’s private law practice leads to another peculiar situation, one that approaches, if not crosses, ethical lines. As a private attorney, Goering represents people who can’t pay their bills or mortgage. Most are declaring bankruptcy. Some face foreclosure as well. And who is hovering over the proceedings to make sure real estate taxes are paid? Goering the treasurer.

“We’re the first lienholder,” says Hamilton County’s chief deputy treasurer Mike Lonneman. “We’re going to get paid before anybody, after court costs.”

Goering’s self-issued permission to leave the treasurer’s office to practice law is not the norm in Ohio’s 88 counties.

“I’d say for the most part it’s uncommon,” says Tom Steenrod, executive director of the County Treasurers Association of Ohio, in Nelsonville. “We have a few people who own farms — and farm — but also go into the office every day. I also know we have some CPAs, but who are very careful because they could have a potential conflict of interest on tax issues. Most spend full time in the office.”

Walsh says Hamilton County voters need to know they’ve not been electing an 8-to-5 treasurer. “It’s been going on for 25 years and it makes you wonder if it’s ever going to change,” he says.

CONTACT JAMES McNAIR: [email protected], 513-665-4700 x142 or @jmacnews