A

series of 12 unusual earthquakes in northern Ohio reached a 4.0 magnitude on New Year’s Eve, shaking homes in Youngstown and intensifying nationwide opposition to fracking, a controversial natural gas extraction process.

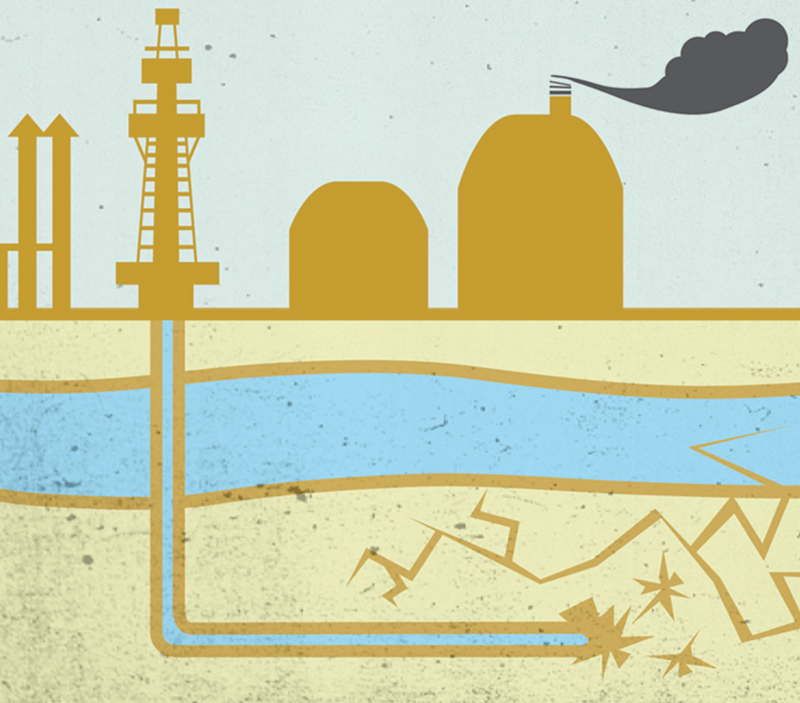

John Armbruster, a Columbia University seismologist hired by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), located the quakes’ epicenters near the base of a wastewater injection well operated by D&L Energy. One of 177 injection wells in Ohio, this one was greasing the palms of a previously unknown fault line, by pumping gas industry wastewater right into it.

In response to the finding, Gov. John Kasich suspended injections at that well and at four inactive sites in the same area.

Those injection wells dispose of wastewater generated by fracking wells, whose job it is to extract natural gas by blasting pressurized slurries of water, chemicals and sand into ancient shale formations, thousands of feet below ground.

Although it hasn’t been known to cause earthquakes, fracking — or horizontal hydraulic fracturing — creates its own problems. Ask Thelma Payne.

Ms. Payne, now 88, and her husband Richard Payne, 91, were asleep in their bed one night in December 2007, when an explosion in their basement blew their Geauga County home straight off its foundations. The couple bounced up and landed safely back on their mattress; the house landed back on its foundation, but was damaged beyond repair.

“I don’t know why we’re here,” says Ms. Payne, who had lived in the home for 51 years. “It just seems like a miracle.”

The blast woke up the neighborhood, and afterward the Paynes and several other families found their drinking wells erupting like fountains. Officials determined that natural gas (which is mostly methane) had bubbled into the neighborhood’s aquifer, entered the Paynes’ home through their plumbing, accumulated in the basement and exploded when the furnace turned on.

The culprit: A fracking well a quarter-mile away, owned by Ohio Valley Energy.

Forty-three households filed a class-action lawsuit, and Ohio Valley installed a water line to bring drinkable water to Bainbridge Township — but not until the neighbors’ lawyers demanded it. Methane polluted their aquifer for the next three years, and the lawsuit was settled in 2011.

Fracking in Ohio is booming rapidly, thanks in part to the barely tapped potential of the vast Utica Shale, a gassy, 445-million-year-old rock formation that lies beneath a third of the state, at a depth of around 7,000 feet. Until last year, only three permits had been granted for horizontal drilling into the Utica, but in 2011 the number exceeded 40.

In 2004 Ohio’s State Legislature repealed the abilities of elected local governments to regulate or refuse gas drilling, instead handing full authority to the industry-friendly ODNR. In 2005, the U.S. Congress ruled to exempt fracking from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

When gas companies are looking to drill in residential areas, they can sometimes lease land from development companies that have retained the mineral rights beneath homes they’ve sold. In those cases, homeowners have no say in the drilling of wells, no matter how close to their homes.

Landowners who are approached directly have choices: They can refuse drilling on their properties, or they can agree to it and accept a nice lease payment for the inconvenience — $10,000 per year is common.

But neighbors who aren’t offered lease contracts have no formal recourse to oppose drilling, even though they may be equally affected by water contamination or declining property values. As a result, many suburban communities have turned to direct action, sometimes with the support of local Occupy movements.

On Nov. 30, seven nonviolent protestors were arrested in Youngstown while blocking a wastewater truck from approaching a D&L injection well.

Meanwhile, ODNR spokespeople stress that fracking itself has not caused these quakes, while carefully avoiding the term earthquake in favor of “low-level seismic event.” Agency spokeswoman Heidi Hetzel-Evans also emphasizes that “there’s been no groundwater contamination in the state of Ohio due to either hydraulic fracturing or injection wells.”

“They’re sticking to their story,” says Ms. Payne, who puzzles over the ODNR’s claim, given her own frightening experience.

Other fracking-related concerns are emerging on a national level.

On Jan. 9 a group of doctors called for a complete moratorium on the practice, while fracking chemicals are evaluated for health risks.

“When it comes to hydro-fracking, our guiding principle for public policy should be the same as the one used by physicians: ‘First, do no harm,’ ” says Adam Law of Cornell Medical College.

And on Jan. 19, three other Cornell researchers contradicted one of the strongest arguments for natural gas, with a new study suggesting that the greenhouse gas footprint of shale drilling actually exceeds that of oil and coal production, due to leaks of potent methane.

Amid these voices, White House support for fracking only appears to be strengthening. A jobs report released in January hails natural gas as the cleanest fossil fuel, whose low cost could spur a U.S. manufacturing boom.

But elsewhere in the world, economic gas gains are being postponed in the name of precaution.

Last October, France became the first nation to ban fracking, and on Jan. 20 Bulgaria followed suit. New Jersey is currently the only U.S. state where fracking is banned.

In Cincinnati, State Rep. Denise Driehaus (D-Price Hill) has sponsored one of three state bills that would tighten fracking regulations: H.B. 345 would put a statewide moratorium on fracking until the completion of an EPA study into its relationship with drinking water resources. H.B. 351 would increase drilling operations’ transparency, in part by making companies disclose every chemical they put in the ground; and Rep. Robert Hagan (D-Youngstown) introduced H.B. 501 earlier this month, to put a moratorium on wastewater injection. ©