Leonard Bernstein would be turning 100 in August, and his centennial is being observed throughout the world. Events planned here are numerous. University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music’s Philharmonia features Bernstein’s overture to Slava! as part of a Feb. 16 concert and a Lenny and Friends on Broadway program for Feb. 25; CCM’s Wind Orchestra offers “Symphonic Dances” from West Side Story and “Three Dance Episodes” from On the Town at a March 2 concert; and there are three additional CCM spring concerts celebrating him.

The Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra offers its Bernstein Centennial program April 20-21. The Pops performs the score to the Oscar-winning film version of West Side Story April 27-29, while the film plays on Music Hall’s big screen. The May Festival’s chorus will sing Bernstein’s Missa Brevis as part of an April 22 concert at Covington’s Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption. The May Festival on May 19 will present Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece of Singers, Players and Dancers at Music Hall. On May 25, Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms is part of another May Festival concert. And Cincinnati Ballet dances to Bernstein’s score to Jerome Robbins’ ballet Fancy Free March 15-18.

So, clearly, the late Bernstein (who died in 1990 at age 72) still matters in Cincinnati and elsewhere. But why is that so?

An acclaimed conductor, composer and media personality from the 1940s on, Bernstein propelled American music and performers to international prominence. West Side Story guarantees his immortality, but it’s only one facet of his breathtaking genius. He remains a powerful influence on everything from the current generation of symphonic conductors to American musical theater, multi-media’s presence in the arts and arts education.

If you’re a Bernstein newbie, start where I did: The 1958 Young People’s Concert “What Does Music Mean?” My parents plunked me in front of the TV because, they explained, Leonard Bernstein was doing a show for kids.

A handsome man began conducting the theme from The Lone Ranger. I recognized the music, but when he began to talk, he didn’t mention the composer or the music’s title; instead, he talked about what music means. I was hooked. He spoke to me as a peer and had a keen instinct for respecting kids’ intelligence.

Bernstein demolished barriers between genres. He showed how The Beatles’ “And I Love Her” exemplified three-part sonata form and how Dvorák used African-American spirituals in his Ninth Symphony. There was no Classical music — it was the world’s music and it belonged to everyone.

By 1958, Bernstein was already an American success story several times over and had inspired a surge in American music, starting by fronting an orchestra.

American conductors owe a huge debt to Bernstein, who was 25 when he got his lucky break on Nov. 14, 1943, replacing an ailing conductor to lead the New York Philharmonic in a concert broadcast nationally on CBS radio. World War II dominated the headlines, but Bernstein’s debut was front-page news in The New York Times.

The real story was an American-born and American-trained musician leading a major orchestra at a time when only European conductors were considered suitable. In 1953, he became the first American to conduct at Italy’s La Scala, working with iconic diva Maria Callas; five years later, he was appointed the New York Philharmonic’s music director.

Bernstein opened the field for generations of American conductors, many of whom he trained at Tanglewood’s summer music program in Boston, including Mark Gibson, head of conducting at CCM.

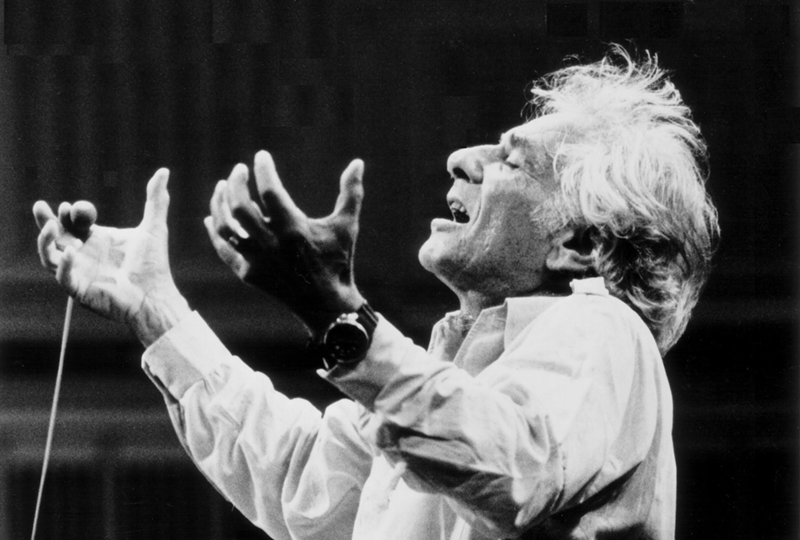

Bernstein’s own conducting still remains a source of debate. His leadership was either revelatory and groundbreaking or self-indulgent and bombastic. He encompassed it all and every move was calculated in service to the music.

That kind of approach was vital as Bernstein passionately advocated for works rarely heard in the late 1950s, especially those by Gustav Mahler. He wasn’t the first Mahler proponent, but Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic frequently performed Mahler and Bernstein was the first to record a complete cycle of Mahler’s nine symphonies in the 1960s.

Bernstein’s musical catalog reflects astonishing variety — symphonies, choral pieces, chamber music, songs, ballets, TV and film scores, a mass and, of course, his works for musical theater.

Those theatrical works are Bernstein’s best and most unabashedly American; they are wildly energetic, full of the rhythms and harmonies of Jazz and Blues that have never lost their appeal. If you only know West Side Story, listen to On the Town, written over a decade earlier, and you’ll hear elements of what would become West Side Story’s Prologue.

That theatricality finds its way into all of Bernstein’s compositions, and listening to his other scores, you’ll hear references to his stage works. Music critics called him out for just that, but to my ears that tonal mix sounds just right.

In every aspect of his career, Bernstein was an unsurpassed educator. He could have invented TED Talks and, thanks to his good looks, immense charisma and ease in front of TV cameras, American audiences loved and listened to him, whether he was talking about a Bach cantata, Blues or The Beatles.

His books remain vibrant and full of insights. The Joy of Music (1959) is a wonderful series of essays that fully convey the title’s intent. Findings (1955) is a revealing self-portrait through letters, essays and other writings.

Failing health prompted Bernstein to state, in the summer of 1990, he would devote the rest of his life to education. He died on Oct. 14, just five days after the announcement.

Leonard Bernstein matters in every part of American life and especially for the American creative community. He would be horrified by today’s political rhetoric and realities, but he might have repeated what he said following John Kennedy’s assassination: “This will be our response to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly, than ever before.”

For more information about CCM events, visit ccm.uc.edu; for the Ballet, cballet.org; for CSO/Pops concerts, cincinnatisymphony.org, for the May Festival, mayfestival.com.