When Chuck Lohre, a Clifton resident and owner of an Over-the-Rhine marketing and communications firm, decided to go to Burning Man in 2016, he wasn’t quite sure what to expect. He was bringing his art installation, a replica of Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machine, to assemble and display in the playa of Nevada’s remote Black Rock Desert, where Burning Man is held for a week around Labor Day every scorching summer. And he had a small camper with a 10-foot fiberglass mako shark atop it — a remnant of when his late father sold shark-leather goods out of the camper in Key West.

But while he went with the right spirit for the imaginatively idiosyncratic and artful event that is sponsored by the nonprofit Burning Man Project, he was nevertheless overwhelmed with the scale, scope and beauty of what he found. There were some 70,000 people on the event’s grounds — activities were centered in the playa and in the temporarily constructed Black Rock City — and they were as devoted to making an impact on their temporary surroundings as he was. And they often had a skewed, Bizarro World-sensibility about how to go about doing that.

And the way the burners — as attendees are called — ended the event seemed more out of a science fiction movie than any known American recreational or religious ceremony. On the penultimate night, they happily burned the giant effigy of the festival’s namesake. Then on the final night, the elaborate Burning Man Temple and its contents were consumed by fire, signifying an acceptance of loss and a determination to find hope in the world outside Black Rock Desert. The Temple has been called “the soul” of Burning Man.

“It’s like you went to another planet with different people living there, different vehicles, different buildings,” Lohre says. “I liked the playa because it was like a wonderful white gallery. It’s just a great (dry) lakebed, sort of like a moonscape, and all of a sudden there are these beautiful people and everybody’s very friendly and welcoming. It’s not like the real world. Everybody there has put in a huge commitment, and that’s really the special part of it.”

There are far more people interested in attending the annual Burning Man event, and especially to see close-up the phantasmagoric and immersive artworks created for playa display and visitor interaction, than have the time, money and constitution to become burners. Tickets are expensive. There is physical hardship involved — heat, sun and winds can be extreme, and there are dust storms that cause blizzard-like whiteout conditions and force people to wear goggles. There is dark humor in the way the search field on the Burning Man website is pre-populated with the phrase “I am lost in a dust storm.”

That’s one reason behind the current No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man exhibit at the Cincinnati Art Museum now through Sept. 2. It was organized by the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, with the collaboration and assistance of the Burning Man Project, and travels to the Oakland Art Museum after Cincinnati. That also may be one reason for the overwhelming public response to the show, which is free and spread throughout the building. On opening day — April 26 — 5,000 people came to see it; over 11,000 showed up just the first weekend. (The show here occurs in two phases — additional art will arrive for exhibition on June 7.)

“I think this exhibition acts as a tease for the type of work you might find on the playa,” says David J. Brown, the guest curator for the show’s Cincinnati installment and a former curator at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center. (Nora Atkinson, craft curator for the Smithsonian American Art Museum, organized the overall exhibition.)

“Audiences are in awe — they’re not expecting the level of technique and creativity, the huge effort, that goes into making the majority of pieces in this exhibition,” he says. “It’s indicative of the kind of activity you can see out there.”

Indeed, Brown has tried to give the exhibit’s stop in Cincinnati some of the sense of discovery that accompanies seeing the art in the playa, where distances are so great that coming across a specific installation is a surprise — even if you’re specifically looking for it. The exhibition is spread throughout the museum, like Nick Cave’s soundsuits were in 2012’s celebrated Meet Me at the Center of the Earth show. The exhibition pamphlet has a map showing the locations of the No Spectators artworks, but doesn’t tell you which is where. (There are directional signposts in the museum proper.)

Here is a selective guide to some of the highlights of No Spectators’ first phase:

Two of the show’s biggest and most remarkable works greet you right after you walk into the museum’s main lobby. To the right, in galleries 147-149 (the Hanna Wing Gallery), is a Burning Man favorite, FoldHaus Collective’s psychedelic “Shrumen Lumen, three tree-sized mushrooms with multi-colored LED lights within their translucent white skins. The mushrooms grow and spread out when you step on their individual floor pads. According to the art museum, there is supposedly still some desert sand in the folds of the giant mushrooms’ skins, which look like plastic mail crates.

Straight ahead of the lobby, at the start of the long, straight Schmidlapp Gallery, is the architecturally overflowing “Paper Arch” by Petaluma, California artists Michael Garlington and Natalia Bertotti. A complicated and time-consuming project, the wood structure of the Arc de Triomphe-like arch has been pasted with reproduced-on-paper imagery to give it a colorful, dazzling surface, like a giant collage. On one top corner, the three-dimensional imagery billows out like a leaping, uncontrollable fire; in other locations there are peepholes where you can look inside and spy on secret scenes. You can also go upstairs to where the museum’s second-floor gallery looks down on the lobby and see the rooftop details of “Paper Arch” — animals, a woman, shells, flower petals, a sheep peeking from within a flower-bordered frame as if trying to survive.“Paper Arch,” like several other artworks in No Spectators, was commissioned specifically for the exhibit. Garlington and Bertotti have previously created two “photo chapels” at Burning Man, but they burned them at the end of the event.

“We go knowing that,” Bertotti says. “It shows the resilience of creativity. We can always build another structure. It’s about not being so attached to one thing that you’re thinking you can never do this again.”

As for the ultimate future of “Paper Arch,” Garlington says, “I see a fiery end.”

Just beyond “Paper Arch” is California artist Richard Wilks’ “Evotrope,” which he calls a “three-point unicycle” and the exhibit refers to as a giant mobile zoetrope because the blades on its centerpiece wheel can be turned so that their eye and fish embellishments move in cinematic fashion.

Gallery 104 holds “Nova,” Christopher Schardt’s point-to-point star-shaped ceiling-hung sculpture. “Nova” features 21,600 LEDs programmed to Classical music. It’s a smaller version of a piece called “Firmament” that he built for the 2015 Burning Man.

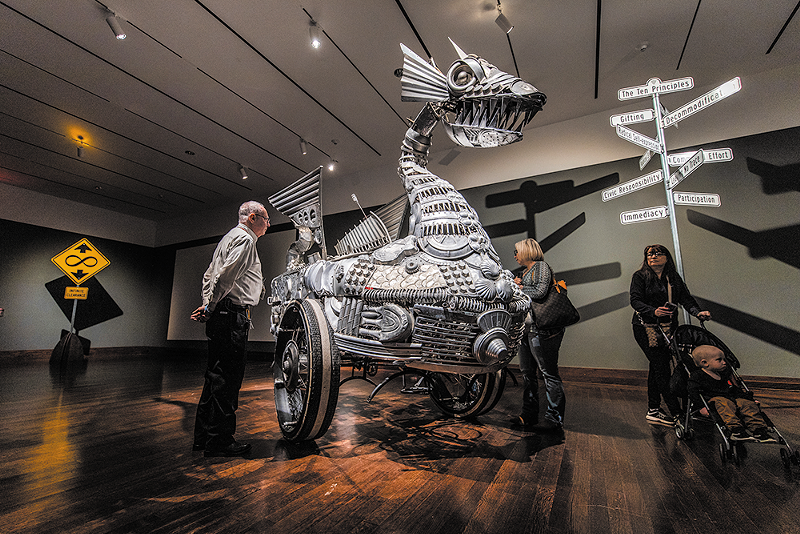

Near it in Gallery 105 is a piece that’s about as far removed from the peaceful, easy feeling that “Nova” engenders as Burning Man is from a small-town county fair. Duane Flatmo’s metallic, monstrous “Tin Pan Dragon” is a pedal-powered kinetic vehicle, a close cousin of Burning Man’s “mutant vehicles” that have been changed so much that they’re almost unrecognizable as a form of transportation. While they still can be driven, they are primarily recognized as artworks. “Tin Pan Dragon,” which the Eureka, California artist brought to Burning Man in 2008, has a metal armature upon which a “skin” of silvery aluminum products, such as kitchen muffin tins, has been applied to give it a look of imposing toughness. Inside are seats where Flatmo and his team can pedal the beastly contraption, and also move its head and toothsome mouth so it shoots out flames.

In No Spectators, it will not spit out fire for safety reasons. So visitors here will miss some of the thrilling effect that burners experienced on the nighttime playa. “The beauty about the dragon is you can work the controls and move that head completely around,” Flatmo says. “Then, people looking at it back up and say, ‘Oh no, I think it’s going to shoot fire at me.’ ”

But they needn’t worry. “Burning Man is very stringent,” he says. “They won’t let anything go out on the playa that’s unsafe. I have a special mechanism, so it only shoots fire when I pull it back and get the head in an upright position.”

The golden gongs of Brooklyn artist Aaron Taylor Kuffner’s “Gamelatron Bidadari” so complement the decorative golden walls of the small Gallery 208 that the piece is easy to miss. But the gentle tones of the Indonesian-influenced music, played when teak robotic mallets strike those 32 gongs, get one’s attention. And it is a delight to watch and hear. Kuffner has displayed previous gamelatrons at Burning Man.

Besides the artwork of No Spectators, there is an ancillary show called City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man in Gallery 124, drawn from the collection of the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno. The ephemera, archival materials and photographs here are poignant — there’s a shadow box displaying enough lost car keys to start up every car in Nevada. There are also shelves containing jars of ashes from past burns of the famous Burning Man. They loom like holy relics.

The City of Dust is also a good place to learn about Burning Man’s countercultural roots, and how it has managed to stay true to them even amid the event’s growth and spreading fame. It started informally in 1986, when Larry Harvey and Jerry James burned a wooden figure at San Francisco’s Baker Beach. As it grew, with input from the Cacophony Society group, police cracked down on the burning. So in 1990, that took place at Black Rock Desert.

In 2000, David Best and Jack Haye created the first Temple to observe the death of a friend — others left notes and offerings, and a powerful new annual tradition was born. Best has gone on to design nine Temples from wood, scrap and other flammable materials. His last was in 2016; it was 80 feet tall, 50 feet wide and needed a crew of 100 people to assemble.

On the Burning Man website, Best has said that “in order for people to feel safe, to feel and express deep emotion so they can heal, the temples must be beautiful and delicate while at the same time being strong to provide comforting support.”

For No Spectators’ showing at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., Best created a hauntingly contemplative, temporary Temple in a second-floor gallery. But it had to be destroyed — according to Cincinnati’s curator Brown. And that left Cincinnati without a temple, something it definitely wanted.

“We basically asked the community — the local burners first — if it was interested in conceiving that,” Brown says. “We had a meet-and-greet in December and over 100 people showed up.”

Samantha Krukowski, a University of Cincinnati College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning associate professor, who is a Burning Man veteran and who has edited the book Playa Dust: Collected Stories from Burning Man, learned about the request from attendees and offered to do it.

She has had students in her now-completed Special Topics in Landscape Architecture studio/charette work with interested community members to build a domed Temple out of honeysuckle, an invasive species that needs to be cleared from the art museum’s hillside in order to create the recently announced Art Climb stairway.

“This isn’t the kind of architecture you design perfectly; honeysuckle has a mind of its own and many students haven’t worked with a real site before,” Krukowski says.

You can see the work-in-progress at the edge of the hillside along the entrance drive to the museum. She wants it finished this month in order to be consecrated by Crimson Rose, a founder of Burning Man, who comes to the art museum on June 6 to speak at the 7 p.m. Benesse Lecture.

On a recent Saturday, in the unseasonably chilly weather, Krukowski was at the site with several others working away. And she appealed for more volunteers in order to get the Temple done on time.

Yet while concerned, she also noticed that passersby had started to leave things — someone had placed a dreamcatcher amid the assembled honeysuckle.

“There’s a level of personalization that’s starting to show,” she says. “There are starting to be these moments where people realize this is participatory.”

Once the Temple is complete, it can’t go inside the museum, Krukowski says, so it will probably stay outside where visitors can leave remembrances to loved ones, as is done in Nevada.

That brings up the question of how to dispose of it when No Spectators finishes its run in Cincinnati on Sept. 2, the same day that the 2019 Burning Man finishes in Nevada. (The Temple burning in Nevada occurs on the event’s last night, Sept. 1.)

A thought is for Cincinnati to have its own Temple burn, but that’s easier said than done. As the museum grounds are part of Eden Park, the Temple would have to be moved off it to be burned.

“The question is how to make a burn meaningful to people who have never been to Burning Man,” Krukowski says. “It’s embedded in the culture in Nevada, but just lighting a big thing on fire in the middle of a city is another thing.

“At the very least, we should be looking at a careful public dismantling event, where pieces of the Temple are relocated and burned along with anything left there. We should be able to manage that, and I think that’s important to do.”

Film and Community at the "Capitol Theater"

The outdoor art installations at the annual Burning Man event in Nevada are often monumental — they need their massive size to make a visual impact amid the seeming endlessness of the remote Black Rock Desert playa that serves as the event’s vast, dusty art gallery. And because they are so tall, complex and heavy, you might think their artists would need a fleet of five-ton cranes to assemble their creations out there in this wilderness.

And, in a way, they do. Five Ton Crane is the name of an Oakland, California-based artist collective that over the years has created some of the most memorable (and cleverly named) Burning Man artworks. It is represented in the Cincinnati Art Museum’s current No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man exhibition by a new piece called “Capitol Theater” — an Art Deco-style movie theater on wheels that shows newly produced silent films for people to sit and watch. It was commissioned by the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which organized No Spectators.

In 2007, Five Ton Crane debuted at Burning Man with “Steampunk Tree House.” In 2009 came “The Raygun Gothic Rocketship,” 2011 brought a Nautilus Submarine art car and the 2015 contribution was “Storied Haven — Big Boot” (gigantic footwear that you could climb up). Five Ton Crane could not contribute any of its previous art installations to this show, as they have since been sold and installed elsewhere.

The collective’s name refers to its sense of purpose rather than to any construction equipment it might own or use — it exists to do the “heavy lifting” for individual artists who desire to work on projects too complex for any one to do alone.

“The group is rather large — it’s more like a network with almost 200 people on our email list,” says Sean Orlando, a Five Ton Crane co-founder who is also the artist/owner of the Engineered Artworks creative design/build art studio. He and Five Ton Crane member Bree Hylkema, an artist/designer whose Obsolete Pictures company produces vintage-style silent films, are the credited lead artists on the “Capitol Theater” project.

But there were many others involved.

“When we come up with projects, we’ll open it up to the group, but then we’ll think of who has specific skill sets or knowledge in a certain area that will best benefit the projects,” Orlando says. “We have metal fabricators, wood fabricators, engineers, painters, clothing designers, jewelers … So we’ll pull from all our resources as a group to build a collaborative art piece.”

“Fine Ton Crane projects are intentionally supposed to be collaborative, to remove the ego of the artist from the equation,” he continues. “Even though it’s led by a lead artist, there is opportunity for all the other artists in the group to express themselves in their own way.”

“Capitol Theater,” commanding center space in the art museum’s second-floor Gallery 216 until Sept. 2, is certainly a sterling accomplishment of large-group expression. Designed to look somewhat like an English double-decker bus with an open-air movie theater on top, it is 12 feet wide, 16 feet high (counting its marquee), about 25 feet long and weighs approximately 4 tons. The collective had to send a team of eight people to Cincinnati to work with museum staff to install the artwork. In the gallery, people step aboard and take a seat to watch five short silent movies with original musical scores (a sixth is in final production and will be added soon). These films were directed by Allen White of Obsolete Pictures and can be stunningly artful, such as the Russian Constructivist-indebted Kokolores: A Modern Dance in Two Acts, or the more devilishly witty Welcome to the Moving Pictures, which instructs viewers on theater courtesy by asking them to “please put away your rotary phones.”

Everything is custom-designed and fabricated by Five Ton Crane, save the axle. Although it doesn’t have an engine at this point, it was conceived to become a moving vehicle — an art car — after the No Spectators museum tour is over. But that doesn’t mean going aboard “Capitol Theater” now is a static experience — it’s designed so you can feel it move when other people ascend or descend, one of its many quirky touches.

“Capitol Theater” is meant to give its visitors a taste of what movie watching was like in the days before films were streamed on large-screen TVs and small-screen smart phones, or seen at drab Big Box multiplexes. It’s designed to recall the Art Deco movie palaces of yore, like downtown Cincinnati’s dearly departed Albee Theatre. Especially its exterior, which is marked by a colorful marquee that crowns the top of the artwork’s front end, a box office where the driver’s cab would be, movie posters and even a few stylish light fixtures hung by Five Ton Crane in the gallery ceiling.

“The whole movie experience was something special you couldn’t do all the time; you certainly couldn’t do it at home,” Hylkema says of movie-going in the 1920s and 1930s. “Theaters were gorgeous, people dressed up and it was an occasion. So this brings that back a little bit.”

But it’d be misleading to label “Capitol Theater” a mere exercise in nostalgia. It has been created in that inimitable Burning Man way that encourages viewers to make all sorts of unexpected and often offbeat discoveries. For instance, while there is a real popcorn maker in the concession stand, the several hundred “popped” kernels inside have all been hand-sculpted by Hylkema out of modeling clay. The wrapped and boxed candy products — which Hylkema designed with Mike Woolson and Katie Keech — all have unusual names. “We weren’t allowed to have any food in the museum,” she explains.

Five Ton Crane also hopes that the Cincinnati volunteers who will work at the “Capitol Theater” box office (which this author has opted to do) get into a suitable Burning Man spirit of role-playing and play-acting.

“One of the positions you can work is to ‘sell’ tickets for the price of a joke or song,” Hylkema says. “That is one of the very, very favorite things about the theater to me. When you connect with somebody and they tell you something real about themselves, or look in your eyes and sing you a song, that’s some really amazing times. And then when they get the ticket, that’s a ticket that really means something to them. It’s their story now, not mine.’’

The CAM's Cameron Kitchin at Burning Man

Coming up in the museum world of the 1990s and 2000s as executive director of the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art and director of the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Cameron Kitchin followed from afar the growth of the annual Burning Man event out at Black Rock Desert in Nevada.

“It felt like a new model of art-making, a new idea about how artists create community,” says Kitchin, the Cincinnati Art Museum’s director since 2014. (He has just signed a new five-year contract.) “I spent time trying to understand the artists and what was happening, and understanding the transformation of a very small grassroots effort into something that grew up along with the energy and creative spirit of the Silicon Valley in 1990s.” (Burning Man’s origins are in California’s Bay Area, where many of its artists still live.)

So, when the museum signed up to be one of the two other cities (the other is Oakland, California) displaying the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum-originated exhibit No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man, he thought the time was right to actually visit the event. He went to the 2018 weeklong Burning Man; what he felt and discovered there was profound.

He flew to Reno and took private transport to the temporary Black Rock City. “I was immediately welcomed,” he says. “The signal of welcome is a hug, an embrace, so you’re immediately greeted with that and then indoctrinated to the desert. I carried in only 23 pounds on my back — very basic needs if you change clothes.”

He stayed at First Camp, where the event’s organizers tend to stay. “I slept in a shipping container — I would say ‘sleep’ is a relative term because nights are like days and days nights, so there’s no clear definition of when anyone takes a rest other than when your body says you need it.”

“I also volunteered while I was there, so there was structure to my time, indicating both a desire on my part and an expectation that everyone be a participant,” he continues. “I volunteered on trash details and on cleaning details and kitchen duties as part of the community of First Camp. And that introduced me to a lot of incredibly hard workers who help to make Burning Man possible.”

In the evenings, when the sun went down and the colorful lights of the artwork transformed the otherwise dark playa, he would ride a bicycle or go in a decorated art car to see some of the several hundred art installations.

“I probably saw a third of them — it’s impossible to see more than that,” he says. “You can see them from a distance, but the spacing between these is massive, and getting from place to place is a full-time enterprise.”

He found himself especially drawn to the Temple. Each year since 2000, a lead artist designs the Temple, and it has achieved a sacred aura as people leave notes or remembrances of people who have passed away. On the last night of Burning Man, the Temple is burned, along with everything left there, in a symbolic act of cleansing and renewal. The 2018 Temple, named Galaxia, was designed by a London-based French architect, Arthur Mamou-Mani. (There was also a second Temple-like structure, a memorial to one of Burning Man’s founders, Larry Harvey, who died in 2018.)

“There is a spirit of grief and processing and an outpouring that is slow but absolutely overwhelming,” Kitchin says. “So it’s a space that I could only spend so much time with. There’s definitely a lot of processing and grief, but it is shared.”

“The sharing is the power of it,” he continues. “I think about those who lost children, those who had troubled relationships with loved ones and had a difficult time in understanding how to let go. And that processing makes it a communal exercise.”

That act of burning, and the way it was witnessed by the participants, gave the Temple an additional, perhaps higher, level of meaning as Contemporary art, Kitchin says. Many of the other installations on the playa, he says, are “intended sometimes for fun, sometimes for provocation, but done knowing that it’s completed when it’s activated by people in the space.”

Yet, some individual artists may also choose to burn their playa creations, and Kitchin had mixed feelings about that. “At Burning Man, the idea you would destroy in order to create does not fit well with the notion of archives, history and preservation at a museum,” he says.

The piece that most pronouncedly made him ponder this conflict was the work “Singularity” by Los Angeles artist Rebekah Waites. She and her team had created a series of houses, ranging in height from 35 feet to 5 inches, located inside bird cages, nesting-egg style. As one walked through the overall piece, wandering ever deeper into the desert-fantasia version of a domestic life, one was meant to hear the echoes of childhood traumas that Waites was channeling. And Kitchin heard them clearly.

“It wasn’t complete until she took that last step (of burning)” Kitchin says. “For me, as a student of art history and a museum professional, seeing that beautiful work of art go from perfection to total elimination was painful. I understood why, but everything I’ve been trained in is that the exquisite object needed to be preserved. And I had to fight with every fiber of being to stand aside and let the artist do what she needed to do to complete the piece.”

Reached in Los Angeles, Waites says she wasn’t originally expecting to burn the work at the event’s conclusion, but one of her team members had put a note inside the piece to his recently deceased father. When visitors saw it, they deluged “Singularity” with similar notes, turning it into an unofficial Temple. And Temples are meant to be burned. “That was very powerful,” she says. “I decided I had to burn the whole thing.” (She did save some of the smaller houses.)

Kitchin came away from Burning Man better understanding the differences between the way the event shows reverence for art and the way an art museum does so. And this knowledge reinforced his commitment to exhibiting No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man.

“It takes what we think we know and contradicts it,” he says of Burning Man. “What better definition is there for innovation and change than that?”

No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man is on display at the Cincinnati Art Museum through Sept. 2. For more information on programs, events, how to participate in the Temple build and attend the June 7 Beyond Black Rock party hosted by the CAM Catalysts group of young-professional museum supporters, visit cincinnatiartmuseum.org.